By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

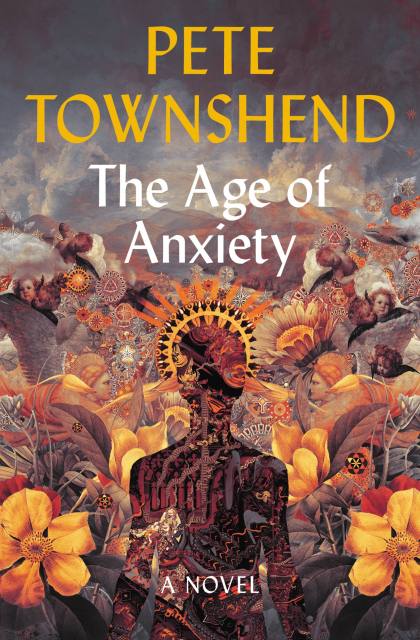

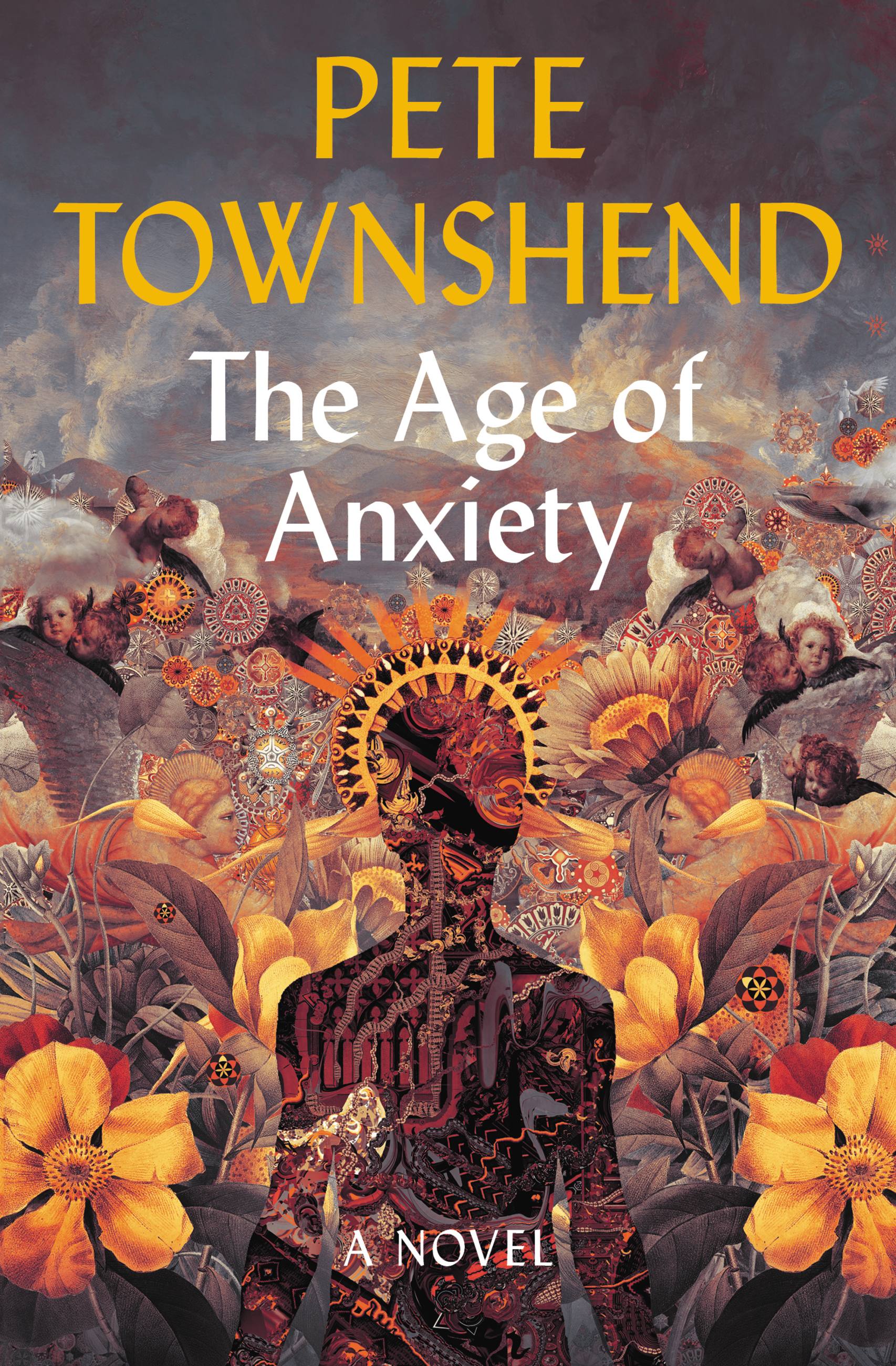

The Age of Anxiety

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316398978

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A former rock star disappears on the Cumberland moors. When his wife finds him, she discovers he has become a hermit and a painter of apocalyptic visions.

An art dealer has drug-induced visions of demonic faces swirling in a bedstead and soon his wife disappears, nowhere to be found.

A beautiful Irish girl who has stabbed her father to death is determined to seduce her best friend’s husband.

A young composer begins to experience aural hallucinations, expressions of the fear and anxiety of the people of London. He constructs a maze in his back garden.

Driven by passion and musical ambition, events spiral out of control — good drugs and bad drugs, loves lost and found, families broken apart and reunited. Conceived jointly as an opera, The Age of Anxiety deals with mythic and operatic themes. Hallucinations and soundscapes haunt this novel in an extended meditation on manic genius and the dark art of creativity.

Genre:

-

"A cracking story about sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll."Mail on Sunday EVENT

-

"A dazzling whirligig of a novel, featuring reclusive rock stars-turned-seers, visions of heaven and hell, young musical pretenders, artists and groupies."Daily Express

-

"Setting his novel in the milieu he knows in all its excess, Townshend directs a cast of memorable characters while examining themes of creativity, genius, music, and love."Daily Mail

-

"The scope of The Age of Anxiety is broader than first appears: this modern-day fable dwells on creativity and madness."Radio Times

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use