By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

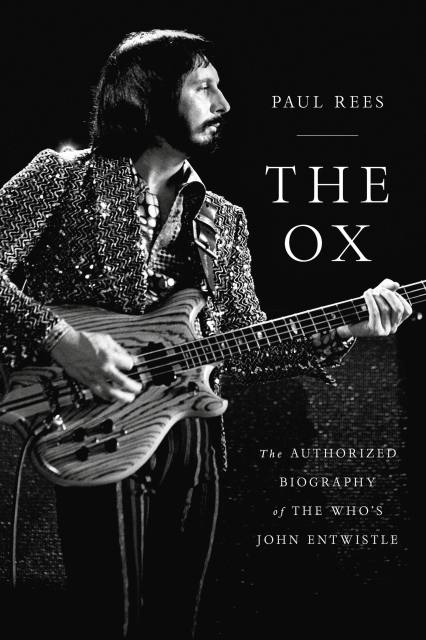

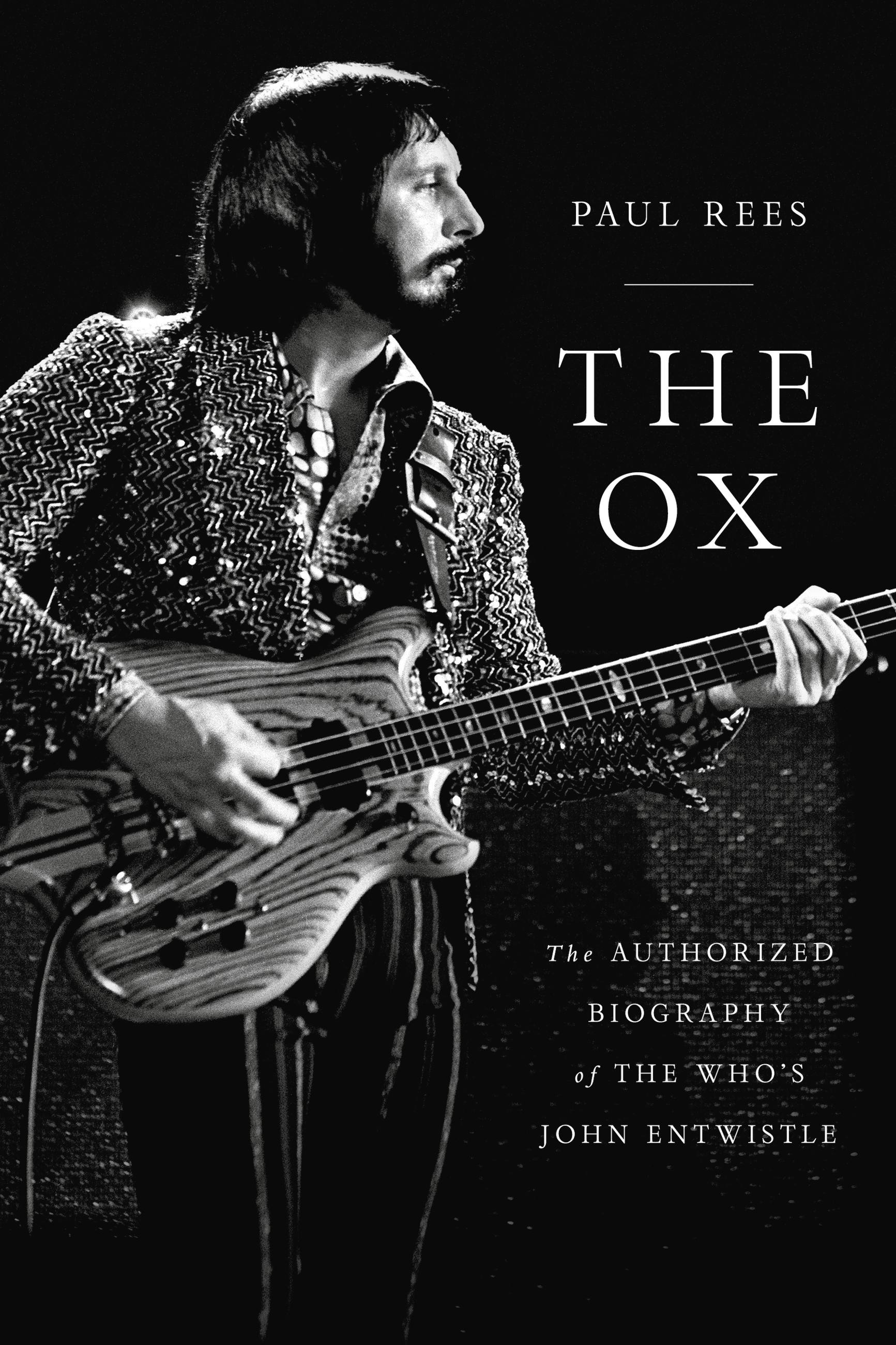

The Ox

The Authorized Biography of The Who's John Entwistle

Contributors

By Paul Rees

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306922879

Price

$12.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

It is an unequivocal fact that in terms of rock bands, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and The Who represent Year Zero, the beginning of all things, ground-breakers all. To that incontrovertible end, John Entwistle—The Who's beloved bassist—remains an enigmatic yet undeniably influential figure. However, unlike his fellow musicians, Entwistle has yet to be the subject of a major biography. In the years since his death, his enduring legacy has been carefully guarded by his loved ones, preventing potential biographers from writing the definitive account of his life-until now. For the first time, and with the full cooperation of the Entwistle family, The Ox shines a long overdue light on one of the most important figures in rock history.

Drawing on his own notes for his unfinished autobiography, as well as his personal archives and interviews with his family and friends, The Ox gives readers a never-before-seen glimpse into Entwistle's two very distinct poles. On the one hand, he was the rock star incarnate—larger than life, self-obsessed to a fault, and proudly and almost defiantly so. Extravagant with money, he famously shipped vintage American cars across the Atlantic without having so much as a driver's license, built progressively bigger and more grandiose bars into every home he owned, and amassed an extraordinary collection of possessions, from armor and weaponry to his trademark Cuban-heel boots. But beneath this fame and flutter, he was also a man of simple tastes and traditional opinions. He was a devoted father and family man who loved nothing more than to wake up to a full English breakfast or to have a supper of fish, chips, and a pint at his local pub.

After his untimely death, many of these stories were shuttered away into the memories of his family and friends. At long last, The Ox introduces us to the man behind the myth—the iconic and inimitable John Entwistle.

Drawing on his own notes for his unfinished autobiography, as well as his personal archives and interviews with his family and friends, The Ox gives readers a never-before-seen glimpse into Entwistle's two very distinct poles. On the one hand, he was the rock star incarnate—larger than life, self-obsessed to a fault, and proudly and almost defiantly so. Extravagant with money, he famously shipped vintage American cars across the Atlantic without having so much as a driver's license, built progressively bigger and more grandiose bars into every home he owned, and amassed an extraordinary collection of possessions, from armor and weaponry to his trademark Cuban-heel boots. But beneath this fame and flutter, he was also a man of simple tastes and traditional opinions. He was a devoted father and family man who loved nothing more than to wake up to a full English breakfast or to have a supper of fish, chips, and a pint at his local pub.

After his untimely death, many of these stories were shuttered away into the memories of his family and friends. At long last, The Ox introduces us to the man behind the myth—the iconic and inimitable John Entwistle.

-

VINYL, "The Top 20 New Music Books"

Best Classic Bands, "Best Music Books of the Year" -

"A rollicking new biography reveals."Daily Mail

-

"A must for any Who Fan, and a highly entertaining read."Houston Press

-

"if you're looking for something worthwhile to read...Hachette Books has just released THE OX."No Treble

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use