By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

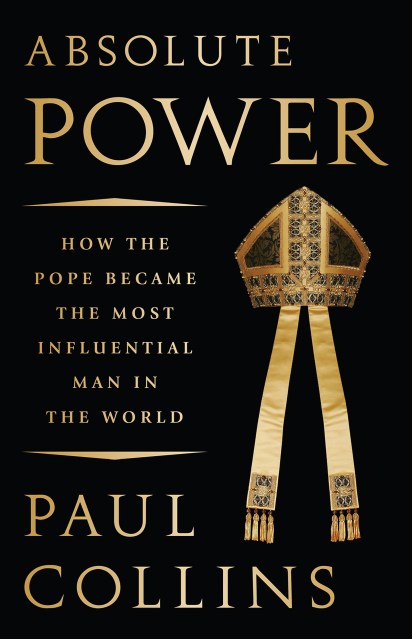

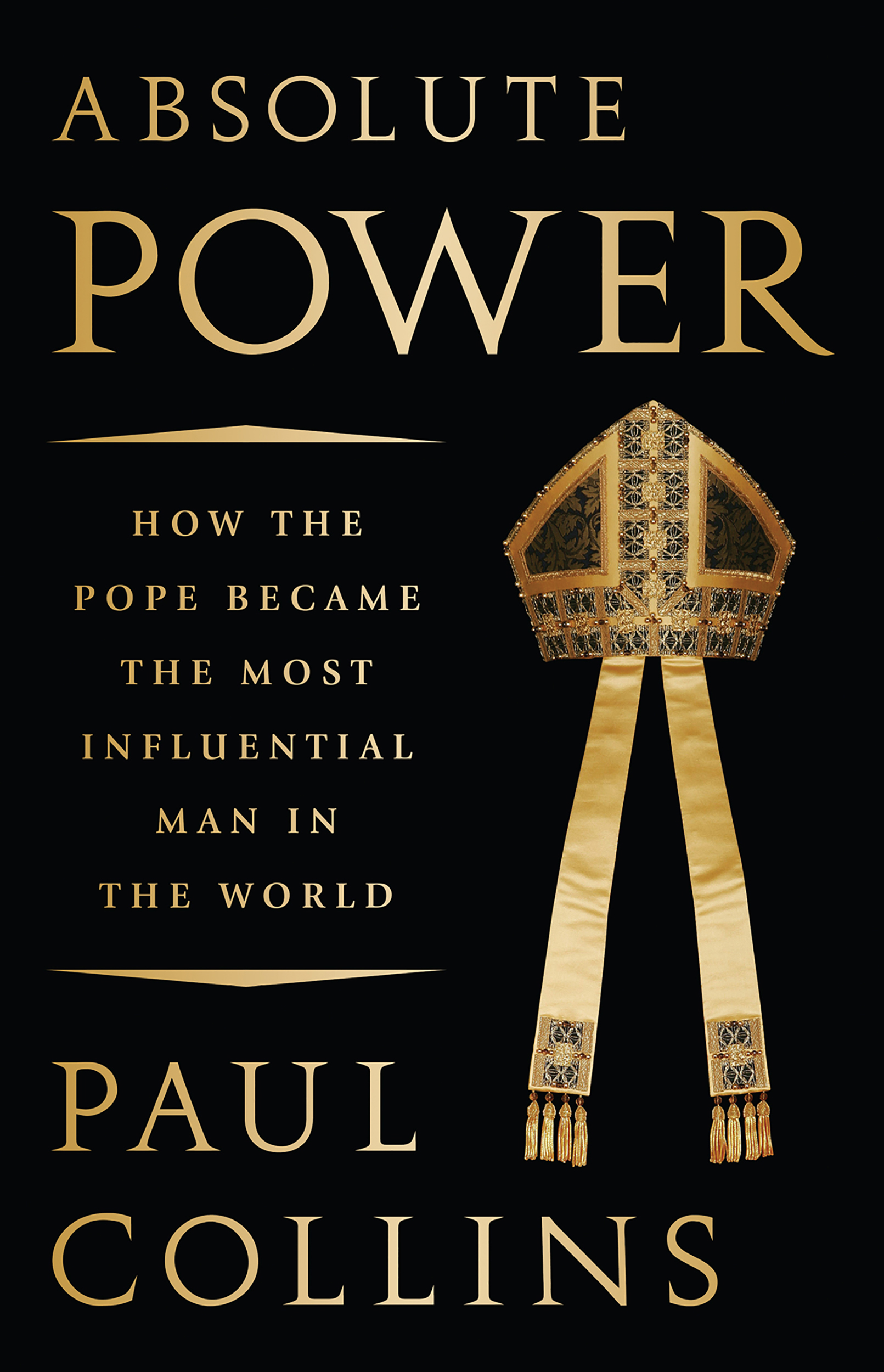

Absolute Power

How the Pope Became the Most Influential Man in the World

Contributors

By Paul Collins

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 27, 2018

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541762008

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 27, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 1799, the papacy was at rock bottom: The Papal States had been swept away and Rome seized by the revolutionary French armies. With cardinals scattered across Europe and the next papal election uncertain, even if Catholicism survived, it seemed the papacy was finished.

In this gripping narrative of religious and political history, Paul Collins tells the improbable success story of the last 220 years of the papacy, from the unexalted death of Pope Pius VI in 1799 to the celebrity of Pope Francis today. In a strange contradiction, as the papacy has lost its physical power — its armies and states — and remained stubbornly opposed to the currents of social and scientific consensus, it has only increased its influence and political authority in the world.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use