Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

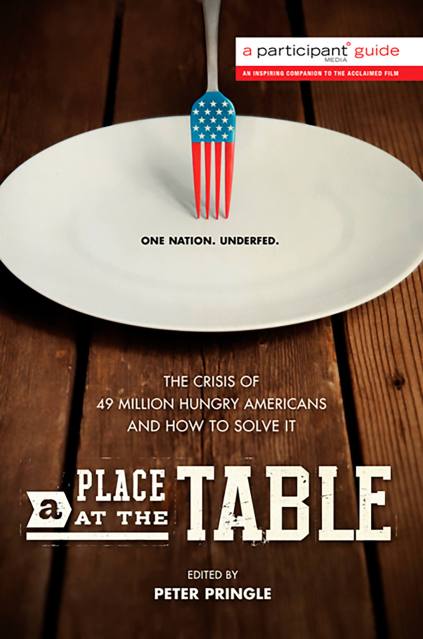

A Place at the Table

The Crisis of 49 Million Hungry Americans and How to Solve It

Contributors

By Participant

Edited by Peter Pringle

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 5, 2013

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391818

Price

$15.99Price

$18.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $18.50 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 5, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Jeff Bridges, Academy Award-winning actor, cofounder of the End Hunger Network, and spokesperson for the No Kid Hungry Campaign, on raising awareness about hunger

Ken Cook, president of Environmental Working Group, unravels the inequities in the Farm Bill and shows how they affect America’s hunger crisis

Marion Nestle, nutritionist and acclaimed critic of the food industry, whose latest work tracks the explosion of calories in today’s “Eat More” environment

Bill Shore, Joel Berg, and Robert Egger, widely-published anti-hunger activists, suggest bold and diverse strategies for solving the crisis

Janet Poppendieck, sociologist, bestselling author, and well-known historian of poverty and hunger in America, argues the case for school lunch reform

Jennifer Harris, of Yale University’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, uncovers the new hidden persuaders of web food advertisers

David Beckmann, head of Bread for the World, and Sarah Newman, researcher on A Place at the Table, explore the intersection of faith and feeding the hungry

Mariana Chilton, director of Drexel University’s Center for Hunger-Free Communities, discusses the health impacts of hunger and the groundbreaking Witnesses to Hunger project

Tom Colicchio, chef and executive producer of television’s Top Chef, presents his down-to-earth case to Washington for increases in child nutrition programs

Andy Fisher, veteran activist in community food projects, argues persuasively why we have to move beyond the charity-based emergency feeding program

Kelly Meyer, cofounder of Teaching Gardens, illuminates the path to educating, and providing healthy food for, all children

Kristi Jacobson and Lori Silverbush, the film’s directors/producers, tell their personal stories of how and why they came to make the documentary

Hunger and food insecurity pose a deep threat to our nation. A Place at the Table shows they can be solved once and for all, if the American public decides — as they have in the past — that making healthy food available, and affordable, is in the best interest of us all.

-

Huntington News

“From Participant Media, the people who brought you "Food, Inc” and Waiting for "Superman" the documentary, scheduled for March 1 release and the companion Participant Guide offer an eye-opening exploration of how we can end hunger in America, maybe even before the 2015 date set by President Barack Obama. The book is based on the documentary but it can be read as a stand-alone look at the hunger problem.”