By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

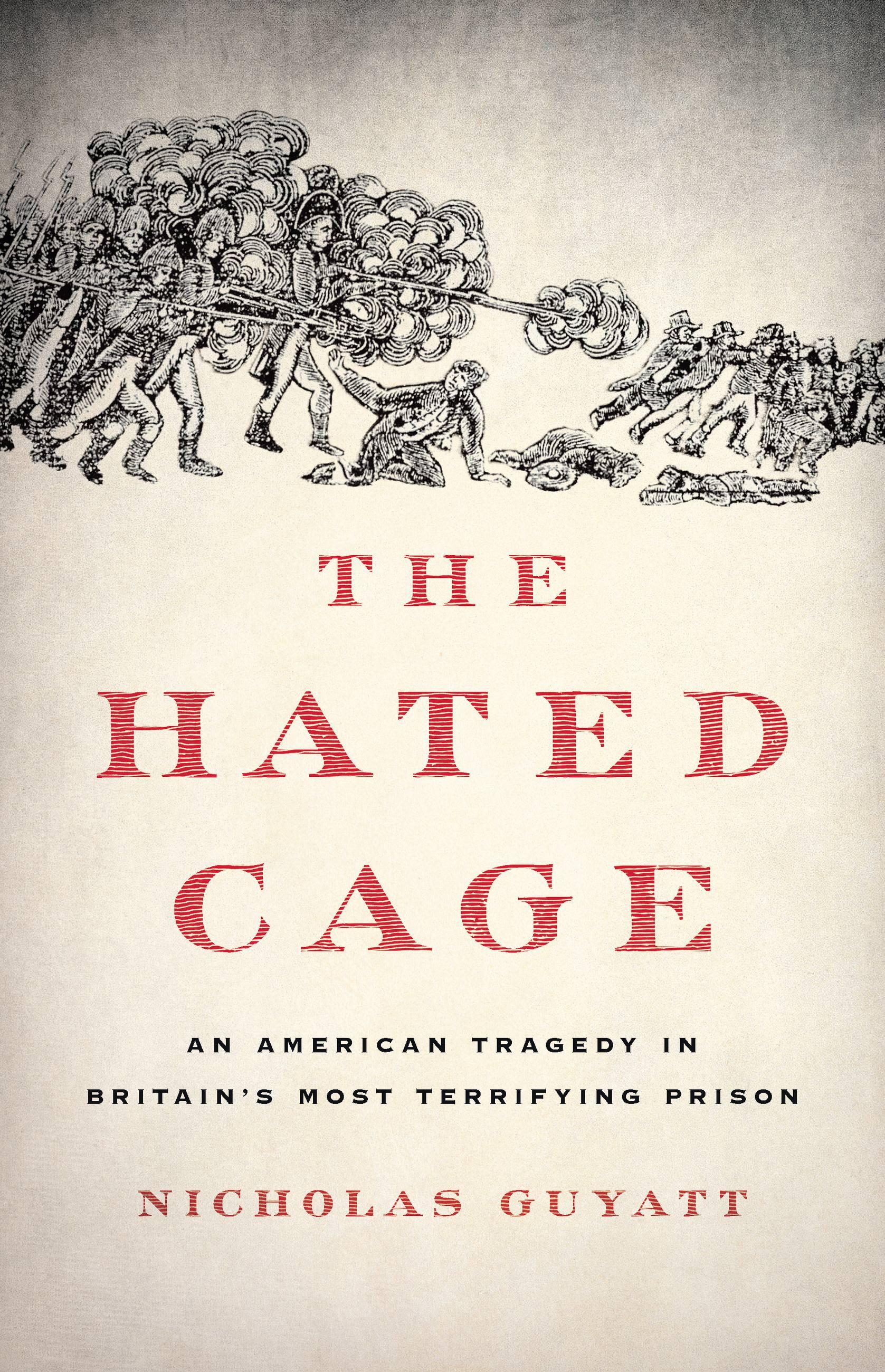

The Hated Cage

An American Tragedy in Britain's Most Terrifying Prison

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2022

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541645646

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A leading historian reveals the never-before-told story of a doomed British prison and the massacre of its American prisoners of war

After the War of 1812, more than five thousand American sailors were marooned in Dartmoor Prison on a barren English plain; the conflict was over but they had been left to rot by their government. Although they shared a common nationality, the men were divided by race: nearly a thousand were Black, and at the behest of the white prisoners, Dartmoor became the first racially segregated prison in US history.

The Hated Cage documents the extraordinary but separate communities these men built within the prison—and the terrible massacre of nine Americans by prison guards that destroyed these worlds. As white people in the United States debated whether they could live alongside African Americans in freedom, could Dartmoor’s Black and white Americans band together in captivity? Drawing on extensive new material, The Hated Cage is a gripping account of this forgotten history.

-

“The Dartmoor Massacre provides the dramatic climax of Nicholas Guyatt’s The Hated Cage, a compelling and compassionate study of the largest overseas contingent of American POWs before World War II… Vivid and convincing.”Stephen Brumwell, Wall Street Journal

-

“Guyatt has written an engrossing account of a little-known incident from the War of 1812 in which over 6,000 Americans were held as prisoners of war in England… A powerful depiction of race relations, international politics, and governmental neglect in the early years of the American republic.”Library Journal (starred review)

-

“With breathtaking revelations, Guyatt illustrates poignantly why the past is not to be disregarded.”Booklist

-

“[A] colorful account… Expertly weaving digressions on the history of incarceration and the racial dynamics of America’s shipping industry into the narrative, Guyatt delivers an engrossing look at an intriguing historical footnote.”Publishers Weekly

-

“In Britain, American military cemeteries dot the landscape, none more forgotten or haunting than the one at Dartmoor, with 271 American sailors from the War of 1812. Guyatt has written a stunning, revealing history of one of the darkest and most inhumane outposts of the British empire, hidden in plain sight and historical memory in southwest England. The book is a withering tale of race and the suffering fate of seamen in the age of sail. It is also a brilliant reminder of why we do research and why we remember.”David W. Blight, Sterling Professor, Yale, and author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

-

“Nicholas Guyatt’s absorbing story of the early nineteeth-century Dartmoor prison ‘massacre’ asks who was an American and could Black men, detained as British as prisoners of war, be citizens? Told by way of archival sleuthing and exacting analysis, The Hated Cage is a fascinating study of how ideas about racism and the state became fused to one another in the early American republic. It is a must-read for anyone concerned with the origins of the anti-Black thought of our own time.”Martha S. Jones, author of Vanguard

-

“In Guyatt’s truly extraordinary recovery of Americans imprisoned long ago, he has excavated a most disturbing racial as well as carceral past, one that will feel disturbingly familiar, and one that underscores on every page the imperative of finally reckoning with white supremacy if there is to be a different future.”Heather Ann Thompson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and its Legacy

-

“In this brilliant book, Nicholas Guyatt tells the fascinating story of a long-forgotten massacre of American sailors in a British prison. While that tale on its own is gripping, The Hated Cage uses this prison drama to unlock a range of insights about life and death across the nineteenth-century Atlantic world. A must-read work.”Kevin M. Kruse, professor of history, Princeton University

-

“This is history as it ought to be — gripping, dynamic, vividly written, and altogether brilliant in its interpretation. Nicholas Guyatt has liberated a motley crew of American sailors from the double darkness of Dartmoor Prison and our own poor historical memory.”Marcus Rediker, author of The Slave Ship: A Human History

-

“Mostly set in a prisoner-of-war camp located on an otherworldly English moor, Nicholas Guyatt’s The Hated Cage is history at its most beguiling. Guyatt expertly synthesizes critical maritime and prison scholarship to give us a unique window into war, repression, racial violence, and incarceration in early modern American history. Anyone interested in exploring the meaning of the American Revolution would do well to lay off its founding fathers and read Guyatt’s account of long-ignored, tellingly so, events in Dartmoor’s ‘Black Prison.’”Greg Grandin, Peter V. and C. Vann Woodward Professor of History, Yale University

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use