By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

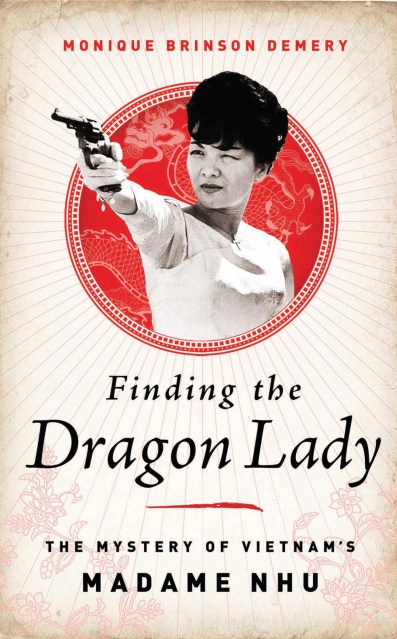

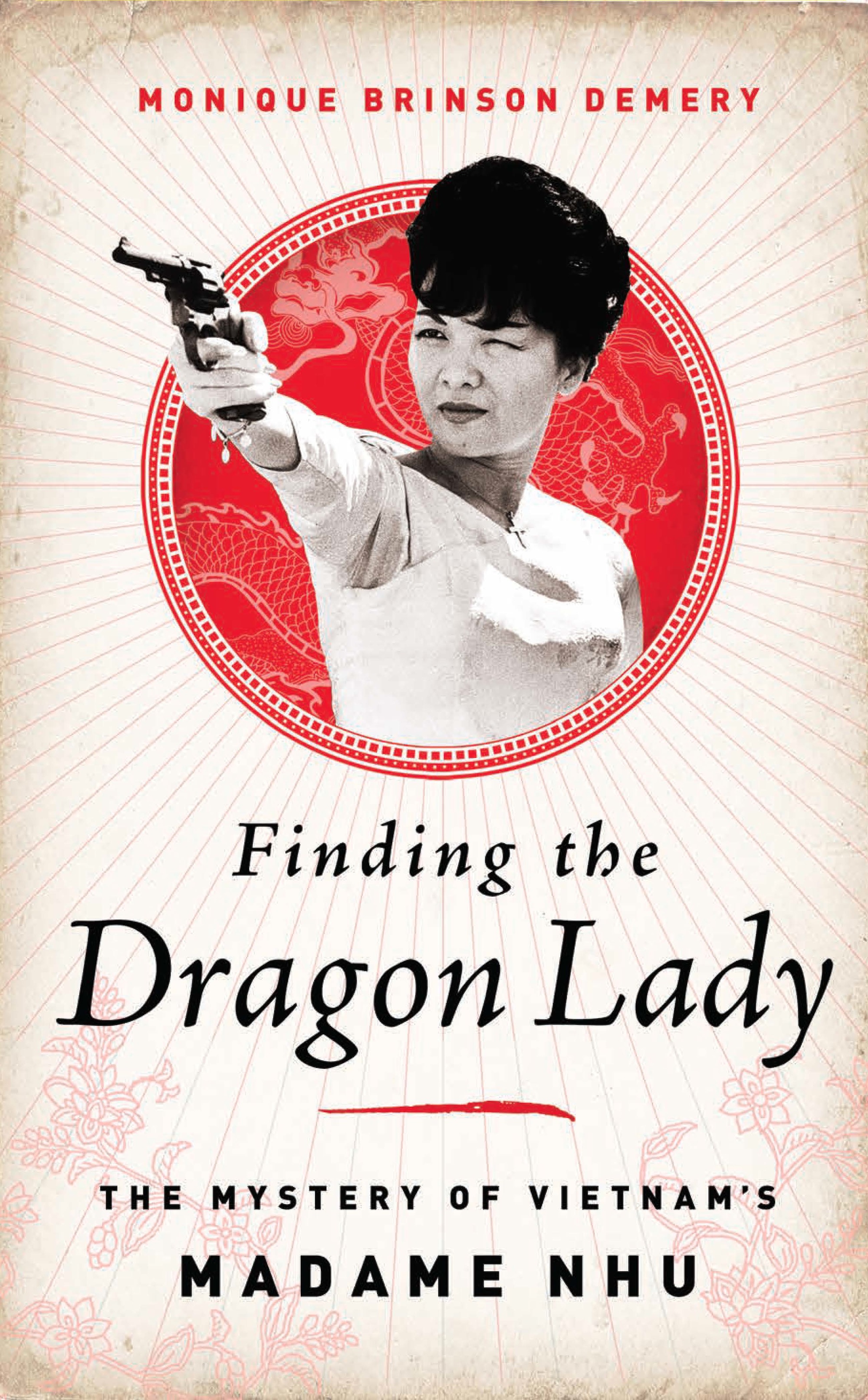

Finding the Dragon Lady

The Mystery of Vietnam's Madame Nhu

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 24, 2013

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610392822

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $18.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 24, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The coup marked the collapse of the Diem government and became the US entry point for a decade-long conflict in Vietnam. Kennedy’s death and the atrocities of the ensuing war eclipsed the memory of Madame Nhu — with her daunting mixture of fierceness and beauty. But at the time, to David Halberstam, she was “the beautiful but diabolic sex dictatress,” and Malcolm Browne called her “the most dangerous enemy a man can have.”

By 1987, the once-glamorous celebrity had retreated into exile and seclusion, and remained there until young American Monique Demery tracked her down in Paris thirty years later. Finding the Dragon Lady is Demery’s story of her improbable relationship with Madame Nhu, and — having ultimately been entrusted with Madame Nhu’s unpublished memoirs and her diary from the years leading up to the coup — the first full history of the Dragon Lady herself, a woman who was feared and fantasized over in her time, and who singlehandedly frustrated the government of one of the world’s superpowers.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use