Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

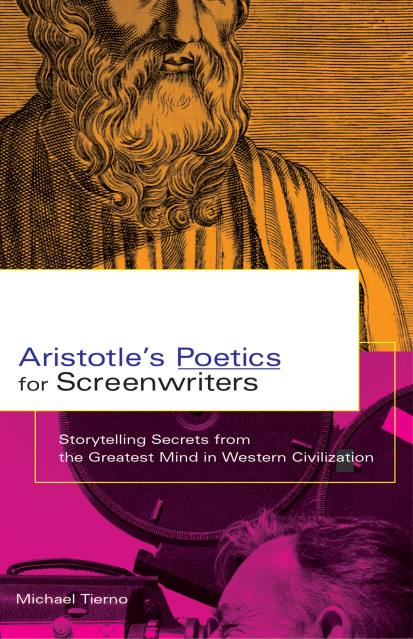

Aristotle's Poetics for Screenwriters

Storytelling Secrets from the Greatest Mind in Western Civilization

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 30, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Long considered the bible for storytellers, Aristotle’s Poetics is a fixture of college courses on everything from fiction writing to dramatic theory. Now Michael Tierno shows how this great work can be an invaluable resource to screenwriters or anyone interested in studying plot structure. In carefully organized chapters, Tierno breaks down the fundamentals of screenwriting, highlighting particular aspects of Aristotle’s work. Then, using examples from some of the best movies ever made, he demonstrates how to apply these ancient insights to modern-day screenwriting. This user-friendly guide covers a multitude of topics, from plotting and subplotting to dialogue and dramatic unity. Writing in a highly readable, informal tone, Tierno makes Aristotle’s monumental work accessible to beginners and pros alike in areas such as screenwriting, film theory, fiction, and playwriting.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 30, 2012

- Page Count

- 192 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781401305567

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use