By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

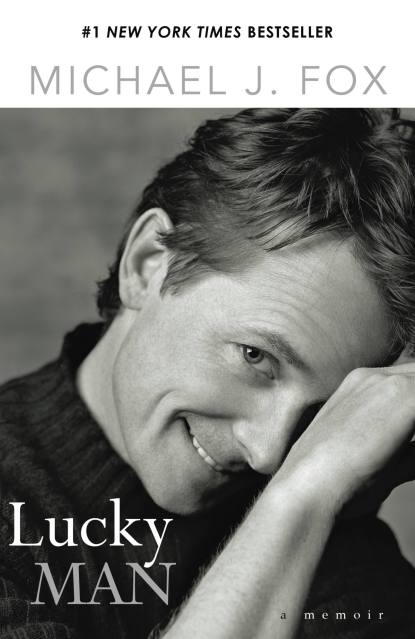

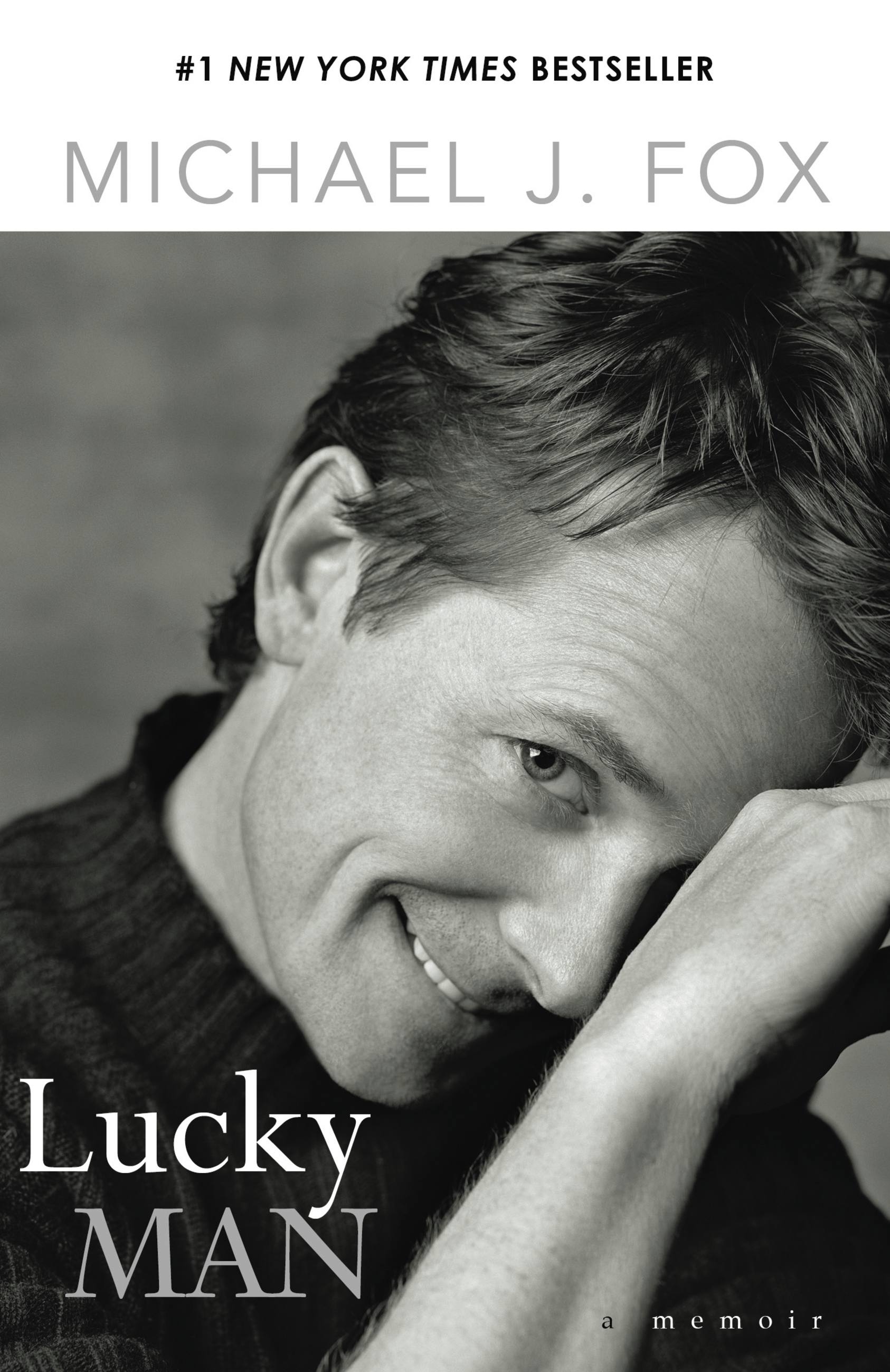

Lucky Man

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 9, 2003

- Page Count

- 260 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781401397791

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 9, 2003. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Michael J. Fox is donating the profits from his book to the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, which is dedicated to fast-forwarding the cure for Parkinson’s disease. The Foundation will move aggressively to identify the most promising research and raise the funds to assure that a cure is found for the millions of people living with this disorder. The Foundation’s web site, MichaelJFox.org, carries the latest pertinent information about Parkinson’s disease, including:

- A detailed description of Parkinson’s disease

- How you can help find the cure

- Public Services Announcements that are aired on network and cable television stations across the country to increase awareness

- Upcoming related Parkinson’s disease events and meetings

- Updates on recent research and developments

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use