By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

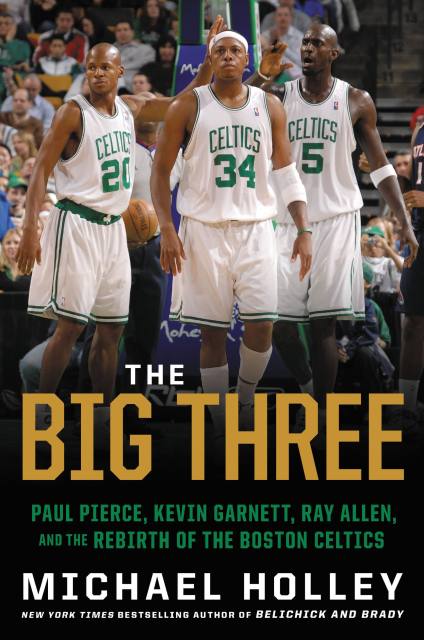

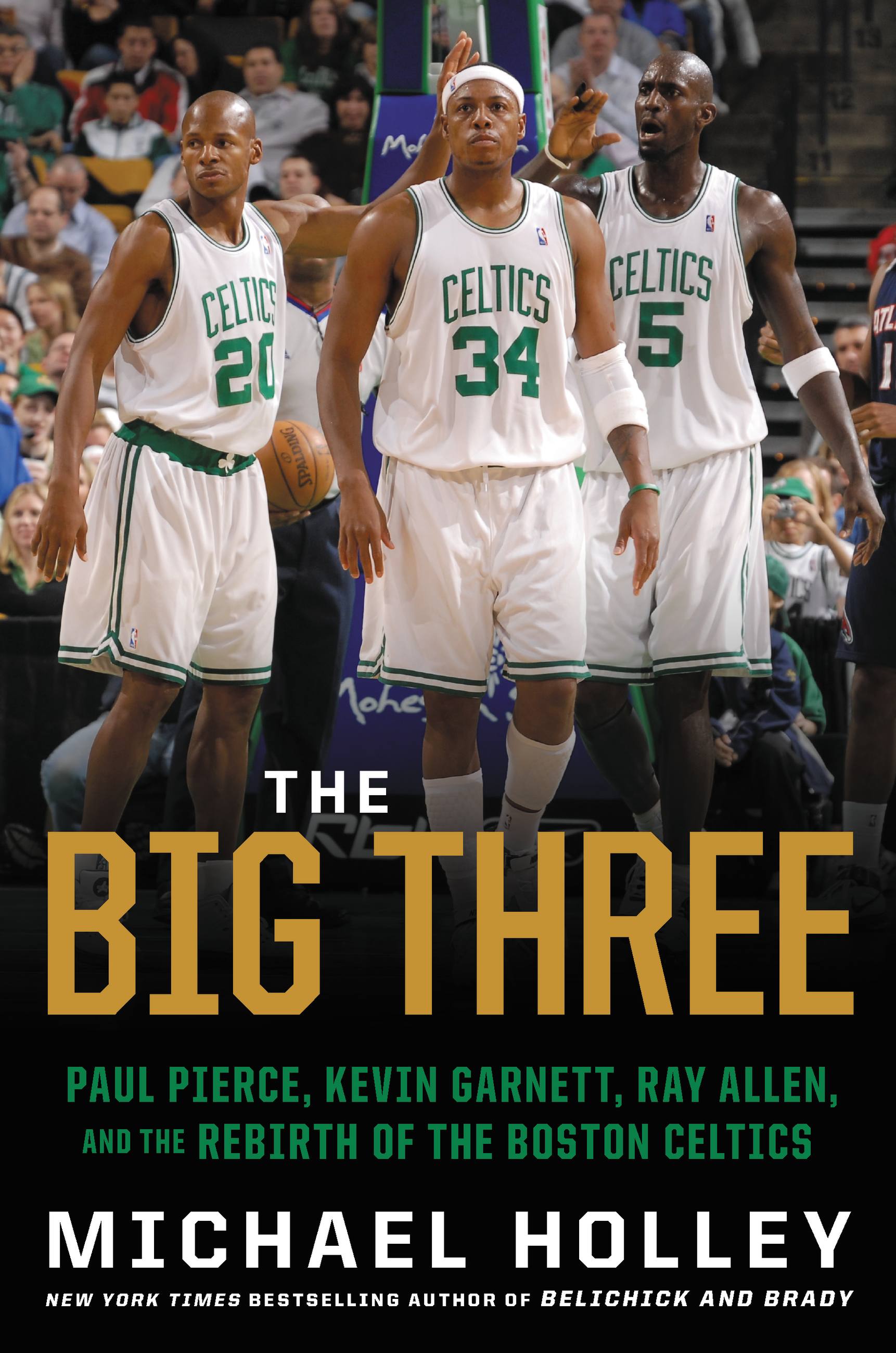

The Big Three

Paul Pierce, Kevin Garnett, Ray Allen, and the Rebirth of the Boston Celtics

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 1, 2020

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316489935

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 1, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

**Selected by the Wall Street Journal among the Best Sports Books of 2021**

A New York Times bestselling sportswriter tells the inside story of how three star players joined together to form the most dominant team in basketball and lead the Boston Celtics to their first championship in more than two decades.

The first of "The Big Three" was Paul Pierce. As Boston Celtics fans watched the team retire Pierce's jersey in a ceremony on February 11, 2018, they remembered again the incredible performances Pierce put on in the city for fifteen years, helping the Celtics escape the bottom of their conference to become champions and perennial championship contenders. But Pierce's time in the city wasn't always so smooth. In 2000, he was stabbed in a downtown nightclub eleven times in a seemingly random attack. Six years later, remaining the sole star on a struggling team, he asked to be traded and briefly became a lightning rod among fans.

Then, in 2007, the Boston Celtics General Manager made two monumental trades, bringing Ray Allen and Kevin Garnett to Boston. A press conference on July 31, 2007 was a sight to behold: Pierce, KG, and Ray Allen holding up Celtics jerseys for the flood of media. Coach Doc Rivers made sure the team bonded over the thought of winning a title and living by a Bantu term called Ubuntu, which translates as "I am because we are." Rivers wanted to make it clear that togetherness and brotherhood would help them maximize their talent and win. What came next—the synthesis of the Celtics' "Big Three" and their dominant championship run—cemented their standing as one of great teams in NBA history, a rival to Kobe Bryant's Lakers and LeBron James's Cavaliers.

This is the team that brought excitement back to the Garden, and therefore to one of the most storied franchises in all of sports. They met their historic rivals, the Lakers, in the 2008 NBA Finals, winning the series in Game 6, in a rout on their home court with a raucous, concert like atmosphere. Along the victory parade route, Paul Pierce smoked a cigar—as a tribute to legendary former Celtics Coach Red Auerbach. In a city now defined by a wealth of championships, "The Big Three" joined the club. Michael Holley, the premier chronicler of Boston sports, brings their story to life with countless untold stories and behind-the-scenes details in another bestselling tome for New England and sports fans across the country.

A New York Times bestselling sportswriter tells the inside story of how three star players joined together to form the most dominant team in basketball and lead the Boston Celtics to their first championship in more than two decades.

The first of "The Big Three" was Paul Pierce. As Boston Celtics fans watched the team retire Pierce's jersey in a ceremony on February 11, 2018, they remembered again the incredible performances Pierce put on in the city for fifteen years, helping the Celtics escape the bottom of their conference to become champions and perennial championship contenders. But Pierce's time in the city wasn't always so smooth. In 2000, he was stabbed in a downtown nightclub eleven times in a seemingly random attack. Six years later, remaining the sole star on a struggling team, he asked to be traded and briefly became a lightning rod among fans.

Then, in 2007, the Boston Celtics General Manager made two monumental trades, bringing Ray Allen and Kevin Garnett to Boston. A press conference on July 31, 2007 was a sight to behold: Pierce, KG, and Ray Allen holding up Celtics jerseys for the flood of media. Coach Doc Rivers made sure the team bonded over the thought of winning a title and living by a Bantu term called Ubuntu, which translates as "I am because we are." Rivers wanted to make it clear that togetherness and brotherhood would help them maximize their talent and win. What came next—the synthesis of the Celtics' "Big Three" and their dominant championship run—cemented their standing as one of great teams in NBA history, a rival to Kobe Bryant's Lakers and LeBron James's Cavaliers.

This is the team that brought excitement back to the Garden, and therefore to one of the most storied franchises in all of sports. They met their historic rivals, the Lakers, in the 2008 NBA Finals, winning the series in Game 6, in a rout on their home court with a raucous, concert like atmosphere. Along the victory parade route, Paul Pierce smoked a cigar—as a tribute to legendary former Celtics Coach Red Auerbach. In a city now defined by a wealth of championships, "The Big Three" joined the club. Michael Holley, the premier chronicler of Boston sports, brings their story to life with countless untold stories and behind-the-scenes details in another bestselling tome for New England and sports fans across the country.

-

“[A] fascinating behind-the-scenes account… Holley includes many revelations…. This clear-eyed look at the vicissitudes of professional sports will appeal even to those who don’t bleed Celtic green.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Michael Holley…skillfully tells the story of how Danny Ainge, who became the Celtics’ honcho in 2003, shrewdly acquired two superstars—Ray Allen and Kevin Garnett—to team with Paul Pierce…. Mr. Holley is good both on these disparate personalities and the nuances of the sport; as an NBA tick-tock, his book is right up there with David Halberstam’s classic The Breaks of the Game.”The Wall Street Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use