Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

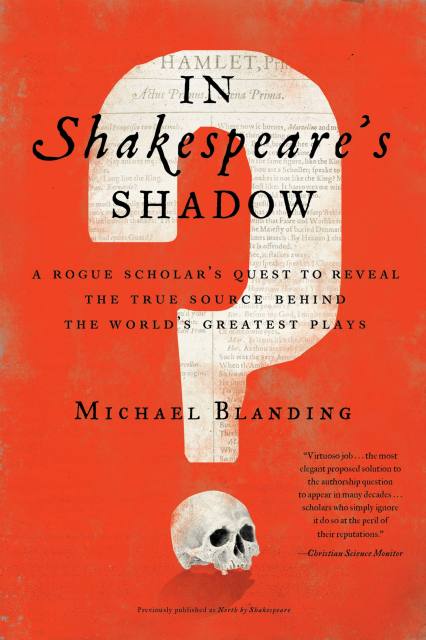

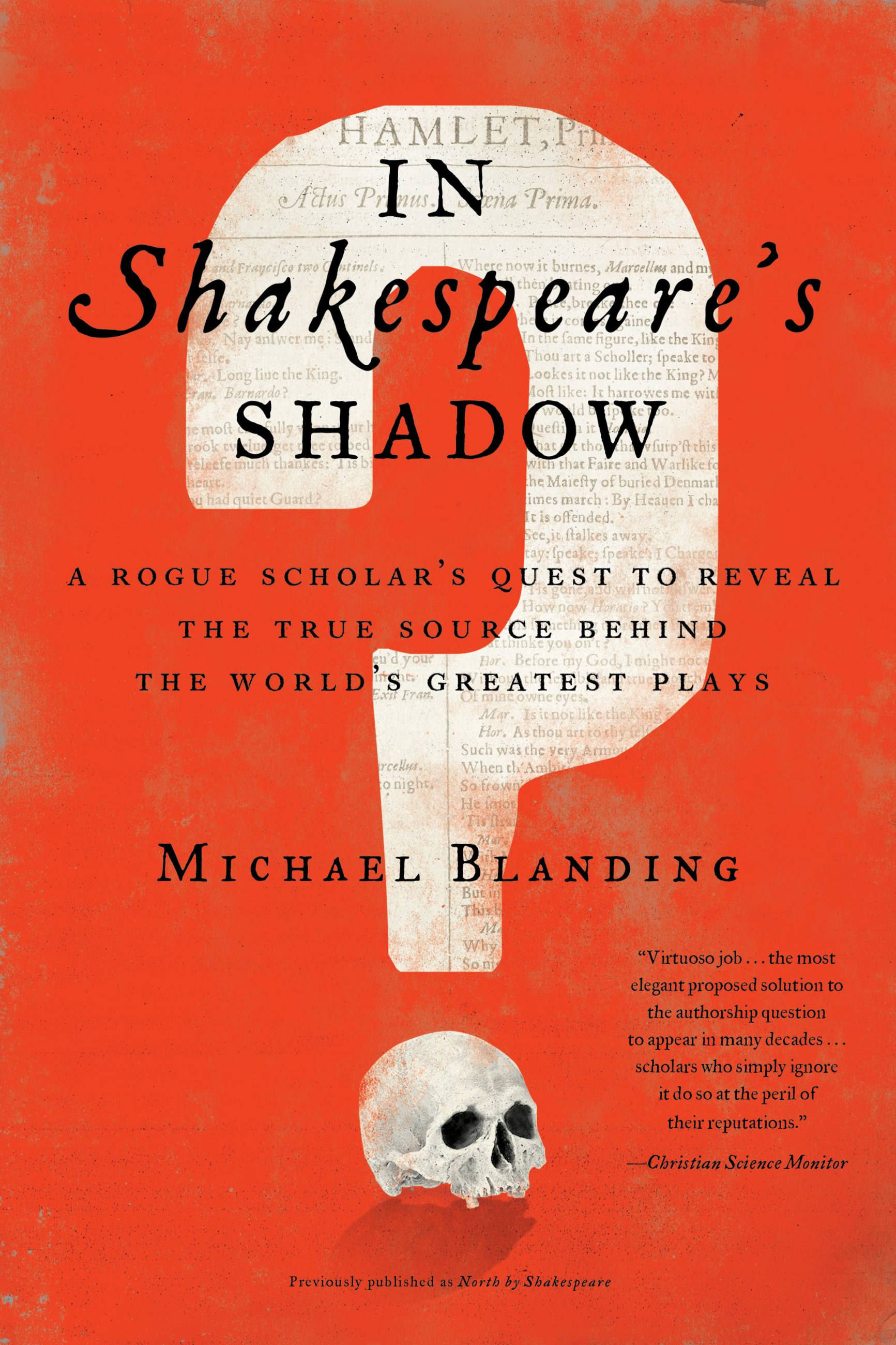

In Shakespeare's Shadow

A Rogue Scholar's Quest to Reveal the True Source Behind the World's Greatest Plays

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 30, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The true story of a self-taught sleuth's quest to prove his eye-opening theory about the source of the world's most famous plays, taking readers inside the vibrant era of Elizabethan England as well as the contemporary scene of Shakespeare scholars and obsessives.

What if Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare . . . but someone else wrote him first? Acclaimed author of The Map Thief, Michael Blanding presents the twinning narratives of renegade scholar Dennis McCarthy and Elizabethan courtier Sir Thomas North. Unlike those who believe someone else secretly wrote Shakespeare, McCarthy argues that Shakespeare wrote the plays, but he adapted them from source plays written by North decades before.

In Shakespeare's Shadow alternates between the enigmatic life of North, the intrigues of the Tudor court, the rivalries of English Renaissance theater, and academic outsider McCarthy's attempts to air his provocative ideas in the clubby world of Shakespearean scholarship. Through it all, Blanding employs his keen journalistic eye to craft a captivating drama, upending our understanding of the beloved playwright and his "singular genius."

Winner of the 2021 International Book Award in Narrative Non-Fiction

Genre:

-

“Did an amateur American sleuth discover a startling new source for Shakespeare’s works? Investigative journalist Michael Blanding journeys across space and time to piece together fascinating evidence that will absolutely transform our interpretation of the classics. North by Shakespeare is a rollicking good tale of detective work, in which an outsider battles the establishment for the soul of the world’s most revered playwright.”Rachel Slade, author of Into the Raging Sea

-

“A dizzyingly complex story, expertly woven together, that takes readers deep into the overlapping worlds of Shakespeare studies, Elizabethan history, and contemporary literary analysis.”Toby Lester, author of The Fourth Part of the World and Da Vinci’s Ghost

-

“Michael Blanding tackles the perennial question of who really wrote Shakespeare’s plays, following the work of an unlikely scholar who dissects the Bard’s language with technological tools that earlier generations had no access to. This compelling take on the age-old quest to understand the foundations of the world’s greatest literature isn’t only a great detective story, it also raises important epistemological questions about how we know what we know in the first place.”Scott Carney, author of What Doesn’t Kill Us

-

“Michael Blanding takes us on a fascinating, eye-opening journey to unlock the centuries-old mysteries surrounding Shakespearean genius, offering fresh insights into Elizabethan history along the way. This captivating book does for English lit what The Da Vinci Code did for the Holy Grail.”Neil Swidey, author of Trapped Under the Sea and The Assist

-

“Once again, Michael Blanding proves himself both a brilliantly dogged reporter and a masterful storyteller. In investigating the scholar who is himself investigating the true source of Shakespeare’s plays, [Blanding] creates one heck of a double, and doubly suspenseful, detective story. Rich with sumptuous historical details and discoveries that ripple through the deepest fault lines of literature, North by Shakespeare is a page-turner that will utterly upend what you think you know about the classics.”Alex Marzano-Lesnevich, author of The Fact of a Body

-

"Part exposition, part narrative, Blanding’s book provides honest insights into the motivations, methods, frustrations, and reverie of scholars grappling with the incomplete record of history, and a revealing picture of what is at stake in scholarly debates about the answers to historical puzzles. Whether or not readers are fully swayed by McCarthy’s arguments about the extent of North’s literary endeavors or his role in shaping Shakespeare’s work, Blanding’s presentation of his quest to build these arguments is both entertaining and provocative."Laurie Johnson, Professor of English and Cultural Studies, University of Southern Queensland, and President, Australian and New Zealand Shakespeare Association

-

“A fascinating detective jaunt through history—all the better for the depth of its scholarship.”Fred Melamed, Actor and Founding Member, Shakespeare & Co.

-

“For readers who love the Bard… this expands our understanding of how the most iconic plays ever written possibly came into existence….The dramatic lives of both men are cleverly illustrated by journalist Michael Blanding, who creates a tense, readable book exploring a bold theory….This fascinating book adds to the narrative behind Shakespeare and presents evidence that may change the way readers see the works forever.”San Francisco Book Review

-

“Blanding dramatizes very effectively the thrill of this literary investigation, giving readers a revelation-by-revelation account of the developments in McCarthy’s thinking without ever drowning them in trivia. The book likewise does a virtuoso job of evoking both the realities of Shakespeare’s world and the twists and turns of the whole Shakespeare question….The most elegant proposed solution to the authorship question to appear in many decades.Christian Science Monitor

“North by Shakespeare gives a curiously invigorating glimpse of that jobbing, hustling Shakespeare….Does [it] finally settle the Shakespeare authorship question?….[T]his isn’t some silly conspiracy theory. Orthodox scholars who simply ignore it do so at the peril of their reputations.” -

"Even the doubtful will enjoy this look into scholarly obsession."Parade

-

"Entertaining...Blanding’s energetic narrative traces McCarthy’s search for more of North’s writings and his use of plagiarism software to provide evidence for their influence on Shakespeare....Highly enjoyable...almost as much fun as sitting in a theater."BookPage

-

“Lively….Blanding does a good job of capturing the eccentric [Dennis] McCarthy and his passion to get to the bottom of this particular rabbit hole. Shakespeare fans and readers who enjoy the thrill of a good bibliographic treasure hunt will want to check this out.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Bardolators will want to read this book.”Library Journal

-

“[Michael] Blanding dives into the ongoing debates over the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays with a lively profile of freelance writer Dennis McCarthy, who has mounted considerable evidence that Shakespeare drew heavily on the works of English translator, lawyer, diplomat, and writer Thomas North…. [A] brisk recounting of North’s life and turbulent times…. An entertaining look at a literary iconoclast."Kirkus Reviews

-

“Fascinating….[a] look at the entertainment industry [in Elizabethan] time and…how in many ways…it is not so different than what we see happens today with artists and creatives….A great history and a great book.”Blog Talk Radio

-

"North by Shakespeare alternates between the enigmatic life of Thomas North, the intrigues of the Tudor court, the rivalries of English Renaissance theater, and academic outsider Dennis McCarthy's attempts to air his provocative ideas in the clubby world of Shakespearean scholarship. Through it all, Blanding employs his keen journalistic eye to craft a captivating drama, upending our understanding of the beloved playwright and his ‘singular genius.’ An inherently fascinating and wonderfully iconoclastic study of meticulously detailed and original scholarship… an extraordinary and unreservedly recommended addition.”Midwest Book Review

-

"This lively narrative [is]… a vibrant, thoroughly enjoyable read.”Fine Books magazine

-

“North by Shakespeare: A Rogue Scholar’s Quest for the Truth Behind the Bard’s Work, is a wildly entertaining read that illuminates a forgotten figure in British history and brings the political intrigue of sixteenth century England to rip-roaring life.”Public Libraries Online

- On Sale

- Mar 30, 2021

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316493284

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use