By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

If It Sounds Like a Quack…

A Journey to the Fringes of American Medicine

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 4, 2023

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541788879

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 4, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A Pulitzer Prize finalist’s bizarre journalistic journey through the world of fringe medicine, filled with leeches, baking soda IVs, and, according to at least one person, zombies.

It’s no secret that American health care has become too costly and politicized to help everyone. So where do you turn if you can’t afford doctors, or don’t trust them? In this book, Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling examines the growing universe of non-traditional treatments — including some that are really non-traditional.

With costs skyrocketing and anti-science sentiment spreading, the so-called “medical freedom” movement has grown. Now it faces its greatest challenge: going mainstream. In these pages you’ll meet medical freedom advocates including an international leech smuggler, a gold miner-turned health drink salesman who may or may not be from the Andromeda galaxy, and a man who says he can turn people into zombies with aerosol spray. One by one, these alternative healers find customers, then expand and influence, always seeking the one thing that would take their businesses to the next level–the support and approval of the government.

Should the government dictate what is medicine and what isn’t? Can we have public health when disagreements over science are this profound? No, seriously, can you turn people into flesh-eating zombies? If It Sounds Like a Quack asks these critical questions while telling the story of how we got to this improbable moment, and wondering where we go from here. Buckle up for a bumpy ride…unless you’re against seatbelts.

-

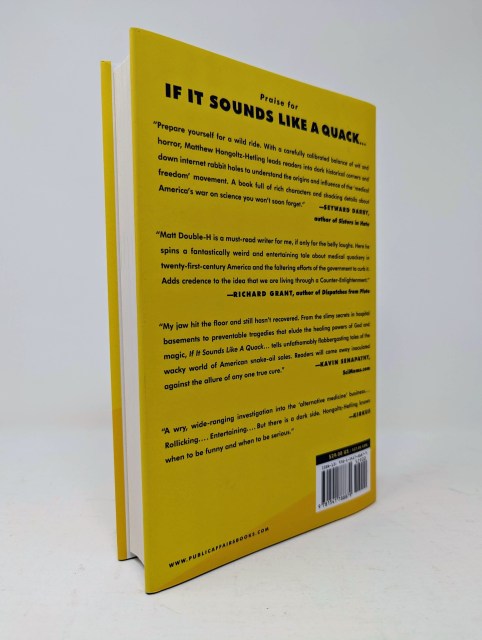

Seyward Darby, author of Sisters in Hate

“Prepare yourself for a wild ride. With a carefully calibrated balance of wit and horror, Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling leads readers into dark historical corners and down internet rabbit holes to understand the origins and influence of the ‘medical freedom’ movement. A book full of rich characters and shocking details about America’s war on science you won’t soon forget.”

-

Richard Grant, author of Dispatches from Pluto

“Matt Double-H is a must-read writer for me, if only for the belly laughs. Here he spins a fantastically weird and entertaining tale about medical quackery in twenty-first century America and the faltering efforts of the government to curb it. Adds credence to the idea that we are living through a Counter-Enlightenment.”

-

Kavin Senapathy, SciMoms.com

“My jaw hit the floor and still hasn’t recovered. From the slimy secrets in hospital basements to preventable tragedies that elude the healing powers of God and magic, If It Sounds Like A Quack . . . tells unfathomably flabbergasting tales of the wacky world of American snake-oil sales. Readers will come away inoculated against the allure of any one true cure.”

-

Kirkus

“A wry, wide-ranging investigation into the ‘alternative medicine’ business…rollicking…entertaining…but there is a dark side. [Hongoltz-Hetling] knows when to be funny and when to be serious.”

-

Publishers Weekly

“Blistering…novelistic…by turns humorous, enraging, and heartbreaking…a powerful antidote to medical disinformation.”

-

Science Magazine

“If It Sounds Like a Quack is a genuine scream: irreverent, very often snarky, sometimes bawdy, but always insightful and well reported.”

-

Marco Eagle News

“If It Sounds Like a Quack is wry, irreverent, and hilarious, poking equal fun at presidents, patients, and quack practitioners alike, while it makes a big point: faux medicine is relatively harmless, until it’s not and someone gets hurt.”

-

Booklist

“Hongoltz-Hetling revels in the weirdness as he recounts a variety of questionable alternative treatments touted by so-called medical freedom movement… Be prepared to both laugh and feel horrified”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use