By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

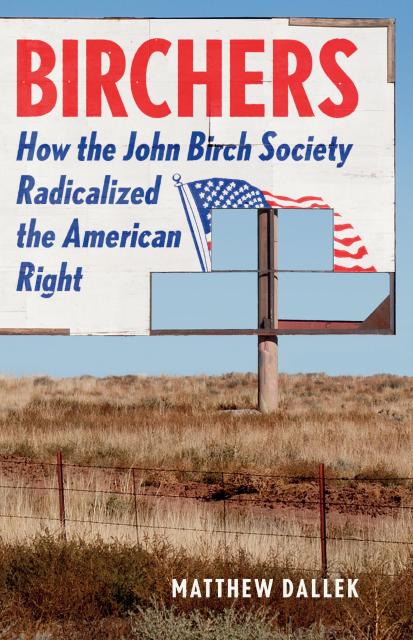

Birchers

How the John Birch Society Radicalized the American Right

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 21, 2023

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541673564

Price

$32.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 21, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

At the height of the John Birch Society’s activity in the 1960s, critics dismissed its members as a paranoid fringe. After all, “Birchers” believed that a vast communist conspiracy existed in America and posed an existential threat to Christianity, capitalism, and freedom. But as historian Matthew Dallek reveals, the Birch Society’s extremism remade American conservatism. Most Birchers were white professionals who were radicalized as growing calls for racial and gender equality appeared to upend American life. Conservative leaders recognized that these affluent voters were needed to win elections, and for decades the GOP courted Birchers and their extremist successors. The far right steadily gained power, finally toppling the Republican establishment and electing Donald Trump.

Birchers is a deeply researched and indispensable new account of the rise of extremism in the United States.

-

“Illuminating…In addition to Dallek’s scrupulous research, he knows how to tell this story with a clarifying elegance and restraint.”New York Times

-

“Dallek’s book is quick-paced and well researched. However troubling, it is a joy to read.”Guardian

-

“Dallek’s account — of the 'halting' and clumsy effort by conservatives to simultaneously exploit and contain Bircher energies — is both well-told and depressingly familiar.”Washington Post

-

"Dallek’s history is valuable for anyone who wants to understand where the conspiratorial and apocalyptic bent in today’s right-wing politics came from... A central lesson of [Dallek's] book is: Don’t assume that just because a group is isolated, kooky, or fringe it will never penetrate the halls of power...Kooks should not be underestimated."Nation

-

“[W]ell-researched work, whose details lay out a society worth remembering, and a history that is relevant for today...”National Review

-

“Impressive new history…You do not have to agree with Dallek’s thesis to find his book worth reading.”Financial Times

-

“What makes Birchers so enthralling, ultimately, is Dallek’s willingness to hold up a mirror to the political establishment, if not his own readership. Birchism’s triumphant return, he suggests, is itself an indictment of the broader liberal project: quagmires in Iraq and Afghanistan have bred a deep distrust of the federal government, while galloping inequality across Democratic and Republican administrations alike has helped create an opening for the Right’s ersatz populism.”Jacobin

-

“Matthew Dallek’s excellent new history, Birchers, argues convincingly that this ‘movement from the 1960s, long thought dead, is casting its shadow across the United States’. Dallek offers not just a definitive history of the John Birch Society but also an insight into how we got to where we are today."Irish Times

-

"Dallek...has waded through thousands of documents to offer a compelling and richly detailed account of the society’s activities in the 1960s...Dallek deserves high praise for disinterring the history of the movement in such minute detail. He amply demonstrates that the conspiracism and hate propagated by the Birchers helped lay the groundwork for the MAGA movement decades later."Washington Monthly

-

“Highly readable.”Jewish Book Council

-

"[A] compelling treatment of the origins, evolution, and integration of a fringe movement into the heart of American conservative politics... Fascinating... Important."Bucks County Beacon

-

“A timely, critically important contribution to the history of our present political and constitutional crisis.”Kirkus, starred review

-

“In this crisp history of the John Birch Society (JBS), [Dallek] details its influence on the radicalization of the modern Republican party…Based on extensive archival research, this timely account of the John Birch Society is essential for readers interested in U.S. political history and far-right extremism.”Library Journal, starred review

-

“Comprehensive and enlightening…This is a treasure trove for political history buffs.”Publishers Weekly

-

“In Cold War America, no organization on the right was larger or more influential than the John Birch Society. Matthew Dallek’s perceptive, engrossing narrative reveals as never before how a group funded by wealthy businessmen and organized at the grassroots level changed the Republican Party—and the nation. Birchers is one of the best and most essential histories of modern conservatism that has ever been written.”Michael Kazin, author of What It Took to Win

-

“The John Birch Society was once considered so far out on the paranoid fringe it was synonymous with kookiness. In his fascinating and scrupulously researched narrative, Dallek shows how the Republican Party’s extremists took over the GOP. Revelatory and readable, Birchers is essential history for anyone trying to understand American politics.”Jane Mayer, author of Dark Money

-

“Before MAGA, there was the John Birch Society, an organization known to many but understood by very few. Dallek has penetrated the fog. His superbly researched and well-written history shows us exactly who the Birchers were and why they mattered—and still matter today.”Sam Tanenhaus, author of The Death of Conservatism

-

“A fascinating and much-needed look at the strange but vital history of the John Birch Society. Long dismissed as a fringe movement, the Birchers and their conspiratorial style have found new life in the Trump-era right. This is just the history we need to understand today’s political predicament.”Beverly Gage, author of G-Man

-

“Birchers is an eye-opening account of the decades-long struggle to organize the radical right in the United States—and to bring the far-right into electoral politics. This deeply researched account exposes the inner workings of the secretive organization, the deep-pocketed and high-powered activists who joined its ranks, and the everyday Americans drawn into its conspiratorial web.”Nicole Hemmer, author of Partisans