Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

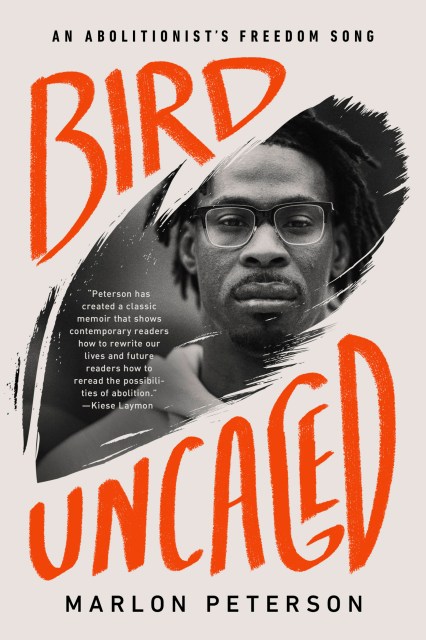

Bird Uncaged

An Abolitionist's Freedom Song

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 13, 2021

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781645036500

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 13, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From a leading prison abolitionist, a moving memoir about coming of age in Brooklyn and surviving incarceration—and a call to break free from all the cages that confine us.

Marlon Peterson grew up in 1980s Crown Heights, raised by Trinidadian immigrants. Amid the routine violence that shaped his neighborhood, Marlon became a high-achieving and devout child, the specter of the American dream opening up before him. But in the aftermath of immense trauma, he participated in a robbery that resulted in two murders. At nineteen, Peterson was charged and later convicted. He served ten long years in prison. While incarcerated, Peterson immersed himself in anti-violence activism, education, and prison abolition work.

In Bird Uncaged, Peterson challenges the typical “redemption” narrative and our assumptions about justice. With vulnerability and insight, he uncovers the many cages—from the daily violence and trauma of poverty, to policing, to enforced masculinity, and the brutality of incarceration—created and maintained by American society.

Bird Uncaged is a twenty-first-century abolitionist memoir, and a powerful debut that demands a shift from punishment to healing, an end to prisons, and a new vision of justice.

Marlon Peterson grew up in 1980s Crown Heights, raised by Trinidadian immigrants. Amid the routine violence that shaped his neighborhood, Marlon became a high-achieving and devout child, the specter of the American dream opening up before him. But in the aftermath of immense trauma, he participated in a robbery that resulted in two murders. At nineteen, Peterson was charged and later convicted. He served ten long years in prison. While incarcerated, Peterson immersed himself in anti-violence activism, education, and prison abolition work.

In Bird Uncaged, Peterson challenges the typical “redemption” narrative and our assumptions about justice. With vulnerability and insight, he uncovers the many cages—from the daily violence and trauma of poverty, to policing, to enforced masculinity, and the brutality of incarceration—created and maintained by American society.

Bird Uncaged is a twenty-first-century abolitionist memoir, and a powerful debut that demands a shift from punishment to healing, an end to prisons, and a new vision of justice.

-

“Marlon Peterson lyrically and powerfully narrates his own experience with the injustices of American prisons, from the cruelty of incarceration to the cages of masculinity. Bird Uncaged is a freedom dream, and important reading for anyone thinking deeply about our carceral systems.”Ibram X. Kendi, National Book Award–winning author of Stamped from the Beginning and How to Be an Antiracist

-

“Marlon Peterson’s memoir tells the intimate story of how the twin forces of patriarchy and white supremacy have combined to build a life of cages for generations of Black men in America. Marlon’s work—a narrative of men who have suffered under, been complicit in, and then attempted to upend their involvement in patriarchal systems—is just the kind of book we need to build toward a liberated future for all Black people in America.”Kimberlé Crenshaw, author of On Intersectionality

-

“Peterson has done what is rarely done in American literature: created a classic memoir that shows contemporary readers how to rewrite our lives and future readers how to reread the possibilities of abolition. This is a stunning memoir that pulls off everything it attempts and somehow it made me want to ask more of myself as a writer, human, and abolitionist.”Kiese Laymon, author of Heavy

-

"Real heroes aren't branded. Many are celebrated far too late. But on rare and triumphant occasions, the people who commit to doing the monumental world-changing work of transformative justice end up being celebrated while they are among us, in community. Marlon Peterson is one of those people. His words are necessary balm. And we need them now more than ever. What a gift he has given us in his debut book. Lives will be forever changed because of his memoir and work."Darnell Moore, author of No Ashes in the Fire

-

"Marlon Peterson's gift is one of immense heart. He carries with him a deep love for humanity, an unwavering faith that we can overcome our challenges, and the righteous spirit of a man committed to being an example of how it's all done. He has been tested throughout his life -- he has had his freedom taken away from him in the most real sense. That has provided Marlon with the kind of perspective often missing from conversations of justice and violence and transformation and healing. Marlon is a healer. His work provides a space for all of us to convene under his wisdom to consider new ways of being in community with one another that honors that we are flawed but respects us enough to believe we are not limited by those flaws. He is nothing short of an inspiration."Mychal Denzel Smith, author of Stakes Is High

-

“Bird Uncaged is heart-wrenching without being sentimental. It’s beautiful without ever being flowery. It’s one voice without ever being just one thing. It’s all honest without ever pretending to be complete. I hope you love it. It deserves to be a thing you love.”Danielle Sered, Author of Until We Reckon: Violence, Mass Incarceration, and a Road to Repair

-

“Bird Uncaged is a story of trauma and survival; a lesson in what it means to confront all of the ugliness of the past and dare journey to forgiveness and something more. Peterson is resolute in these lines, because he has seen enough to know that the healing and the hope is in the journey. The journey found in these pages isn’t just a coming of age story, but rather is a crucially important confronting the ways a man has hurt and been hurt, and come to believe honesty might be a pathway away from shame and more suffering.”Reginald Dwayne Betts, author of Felon

-

“Bird Uncaged is an exquisitely excruciating exercise in emotional excavation that is at once a profoundly personal story as well as a sweeping indictment of this country’s systems and norms and practices. Bravo, Marlon. I am grateful for your intrepidity, voice, and humanity.”Sophia Chang, author of The Baddest Bitch In The Room

-

“In Bird Uncaged, Marlon Peterson offers compelling insights from his remarkable life story. It is a tale for our times: how a young man of promise ends up finding meaning and direction despite numerous challenges and obstacles, not least of which is a lengthy stint in prison. Bracingly powerful and painfully honest, Bird Uncaged is a call for change that should be read by anyone with an interest in justice in the United States.”Greg Berman, executive director of the Center for Court Innovation

-

“Marlon Peterson’s Bird Uncaged: An Abolitionist’s Freedom Song is a viscerally honest, bracingly insightful, exquisitely lyrical memoir that is impossible to put down and even more impossible to ever forget having read. It is raw testimony. It bears witness to modern-day slavery. And it is a full-on education: about what America is and what it foolishly imagines itself to be. The book should be required reading in schools from one end of the USA to another.”Dr. Baz Dreisinger, author of Incarceration Nations

-

“Challenging the typical ‘redemption’ narrative and assumptions about justice, Peterson draws from his time in jail and explores the vulnerability that comes with exposing one’s trauma.”The Root

-

“Over 50 years ago, Maya Angelou told us why the caged bird sings. Now in the 21st century, Marlon Peterson, a formerly incarcerated advocate, continues the legacy as he calls for us to break all cages that confine us: from prisons to toxic masculinity to poverty and beyond. In this timely memoir, he shares how one traumatic moment changed his life forever and made him rethink everything we’ve been taught about justice and redemption.”Elle

-

“A worthwhile contribution to evolving conversations on race and criminal justice.”Kirkus

-

“Peterson embraces the hard work of getting clear on the societal racism that disallows Black and brown humanity; on one’s own agency and choices; and on the abusive prison system that isn’t working. Peterson’s writing is straightforward, both about his experience and himself, and confirms that not acknowledging the humanity of those involved in violent crime and allowing incarceration to remain as is results in amplified destruction.”Booklist