By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

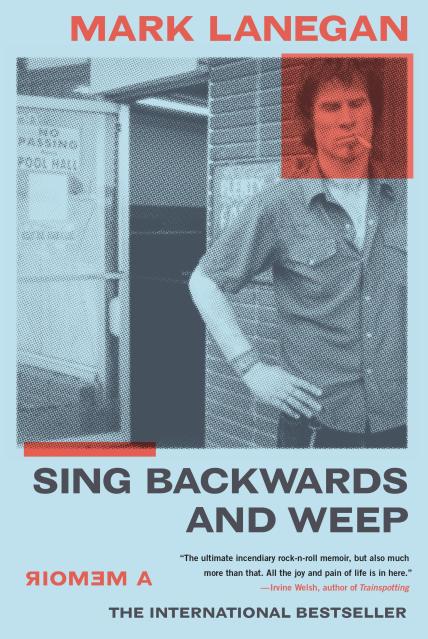

Sing Backwards and Weep

A Memoir

Contributors

By Mark Lanegan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 27, 2021

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306922787

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $39.00 $49.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 27, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This gritty bestselling memoir by the singer Mark Lanegan of Screaming Trees, Queens of the Stone Age, and Soulsavers documents his years as a singer and drug addict in Seattle in the ’80s and ’90s.

When Mark Lanegan first arrived in Seattle in the mid-1980s, he was just “an arrogant, self-loathing redneck waster seeking transformation through rock ‘n’ roll.” Little did he know that within less than a decade he would rise to fame as the frontman of the Screaming Trees and then fall from grace as a low-level crack dealer and a homeless heroin addict, all the while watching some of his closest friends rocket to the forefront of popular music.

In Sing Backwards and Weep, Lanegan takes readers back to the sinister, needle-ridden streets of Seattle, to an alternative music scene that was simultaneously bursting with creativity and dripping with drugs. He tracks the tumultuous rise and fall of the Screaming Trees, from a brawling, acid-rock bar band to world-famous festival favorites that scored a hit number five single on Billboard’s alternative charts and landed a notorious performance on Late Night with David Letterman, where Lanegan appeared sporting a fresh black eye from a brawl the night before. This book also dives into Lanegan’s personal struggles with addiction, culminating in homelessness, petty crime, and the tragic deaths of his closest friends. From the back of the van to the front of the bar, from the hotel room to the emergency room, onstage, backstage, and everywhere in between, Sing Backwards and Weep reveals the abrasive underlining beneath one of the most romanticized decades in rock history-from a survivor who lived to tell the tale.

Gritty, gripping, and unflinchingly raw, Sing Backwards and Weep is a book about more thanjust an extraordinary singer who watched hisdreams catch fire and incinerate the groundbeneath his feet. It’s about a man who learnedhow to drag himself from the wreckage, dust offthe ashes, and keep living and creating.

“Mark Lanegan—primitive, brutal, and apocalyptic. What’s not to love?” —Nick Cave, author of The Sick Bag Song and The Death of Bunny Munro

When Mark Lanegan first arrived in Seattle in the mid-1980s, he was just “an arrogant, self-loathing redneck waster seeking transformation through rock ‘n’ roll.” Little did he know that within less than a decade he would rise to fame as the frontman of the Screaming Trees and then fall from grace as a low-level crack dealer and a homeless heroin addict, all the while watching some of his closest friends rocket to the forefront of popular music.

In Sing Backwards and Weep, Lanegan takes readers back to the sinister, needle-ridden streets of Seattle, to an alternative music scene that was simultaneously bursting with creativity and dripping with drugs. He tracks the tumultuous rise and fall of the Screaming Trees, from a brawling, acid-rock bar band to world-famous festival favorites that scored a hit number five single on Billboard’s alternative charts and landed a notorious performance on Late Night with David Letterman, where Lanegan appeared sporting a fresh black eye from a brawl the night before. This book also dives into Lanegan’s personal struggles with addiction, culminating in homelessness, petty crime, and the tragic deaths of his closest friends. From the back of the van to the front of the bar, from the hotel room to the emergency room, onstage, backstage, and everywhere in between, Sing Backwards and Weep reveals the abrasive underlining beneath one of the most romanticized decades in rock history-from a survivor who lived to tell the tale.

Gritty, gripping, and unflinchingly raw, Sing Backwards and Weep is a book about more thanjust an extraordinary singer who watched hisdreams catch fire and incinerate the groundbeneath his feet. It’s about a man who learnedhow to drag himself from the wreckage, dust offthe ashes, and keep living and creating.

“Mark Lanegan—primitive, brutal, and apocalyptic. What’s not to love?” —Nick Cave, author of The Sick Bag Song and The Death of Bunny Munro

-

"The artist's journey to find one's true voice can travel some very dark roads; addiction, violence, poverty, and soul-crushing alienation have taken the last breath of many I have called friend. Mark Lanegan dragged his scuffed boots down all of those bleak byways for years, managed to survive, and in the process created an astonishing body of work. Sing Backwards and Weep exquisitely details that harrowing trip into the heart of his particular darkness. Brutally honest, yet written without a molecule of self-pity, Lanegan paints an introspective picture of genius birthing itself on the razor's edge between beauty and annihilation. Like a Monet stabbed with a rusty switchblade, Sing Backwards and Weep is breathtaking to behold but hurts to see. I could not put this book down."D. Randall Blythe, author of Dark Days and lead vocalist of Lambof God

-

"If you ever wondered how Mark Lanegan's music came to blossom, here's a taste of the dark dirt that fertilized it. But saying that, or something like it, feels irresponsible, almost like saying 'If you want to make great, soul-shattering art, traumatize yourself to the limit and beyond' ... Sing Backwards and Weep is gnarly, naked, and true."Michael C. Hall of Dexter and Six Feet Under

-

"Harrowing, edgy, tense, and hypnotic. A very truthful, sobering account of what it's like in the throes of addiction, with shades of Bukowski, Burroughs, and Hunter S. Thompson."Gerard Johnson, director and writer of Tony, Hyena, and Muscle

-

"Some books amuse you, some intrigue you, and some-they don't come along often-like Mark Lanegan's Sing Backwards and Weep, squeeze you by the throat and drag you down the back stairs of the author's soul and blast you till you see what he's seen and feel what he's felt. Mark Lanegan spares no detail of the toxic and maniacal things he's done and had done to him, nor of the glorious, weird beauty he walked out with on the other side. You can't look and you can't look away. This is my kind of book. Fucked-up, full of heart, and hard-core as a shot of battery acid in the eye."Jerry Stahl, author of Permanent Midnight, I, Fatty,and Happy Mutant Baby Pills

-

"A no holds barred memoir of uncompromising honesty. All of the usual suspects are here-sex, drugs, rock and roll-and if that were all, it would be compelling enough on the strength of Lanegan's writing and the setting of 80's and 90's Seattle, a near mythical time and place in music history. But what elevates Sing Backwards and Weep above the pack is the window into Lanegan's development as an artist, from his first musical influences to the singular singer and songwriter we see today. He seamlessly weaves that storyline into the more conventional rock memoir fabric and the results are outstanding."Tom Hansen, author of AmericanJunkie and This Is What We Do

-

"Sing Backwards and Weep is powerfully written and brutally, frighteningly honest. First thought that came to my mind was, 'Mark Lanegan gives the term bad boy a whole new meaning.' These are gritty, wild tales of hardcore drugs, sex, and grunge. But this is also the story of a soulful artist who refused the darkness when it tried to swallow him whole. And who found redemption through grace and the power of his unique and brilliant music. Finally, the song becomes truth. And the truth becomes song."Lucinda Williams

-

"A stunning tally of the sacrifices that sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll demand of its mortal instruments."Kirkus Reviews

-

"It's a hell of a read. All-consuming, even. Be warned."Louder Than War

-

"In a gritty new memoir, Sing Backwards and Weep, Lanegan offers an unflinching look at his shadowy past, stretching from childhood up until the death of his friend Staley in 2002. The book reads like a debauched Bukowski novel, as Lanegan drifts from sin to sin, cursing those who held him back from music, drugs, and hookups, and recounting grisly tales about his famous friends."Rolling Stone

-

"A dark, gripping and compelling piece of work."Guerrilla Candy

-

"Rather astonishing... [it] reads kind of like the grunge-scene Andy Warhol Diaries: check the index, and there's probably a great story about your favorite artist."Minnesota Public Radio, "The Current"

-

"MARK LANEGAN'S AUTOBIOGRAPHY IS THE MOST RAW AND BRUTAL ROCK MEMOIR EVER WRITTEN... [This book is] one of the most unflinching memoirs in the history of music writing."Kerrang!

-

"[Sing Backwards and Weep] unflinchingly tells the musician's hardscrabble story."SPIN

-

"[A]n extraordinary snapshot of the reality lower down the totem pole.... one of the most compelling accounts of squalor and misery ever committed to paper. In comparison, Bukowski at his most fevered reads like Somerset Maugham."New Statesman

-

"[A] fearsome and brutal new autobiography."Washington Post

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use