Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

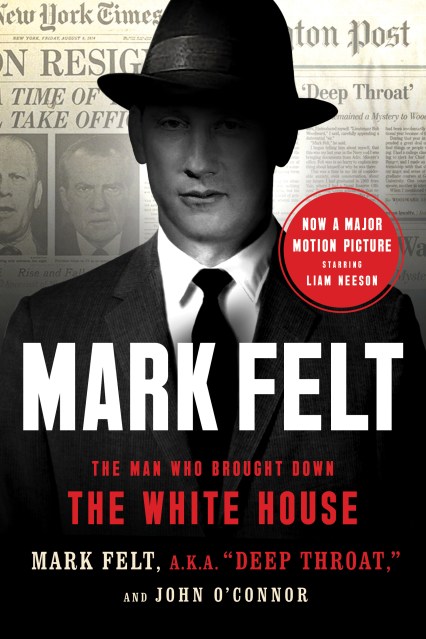

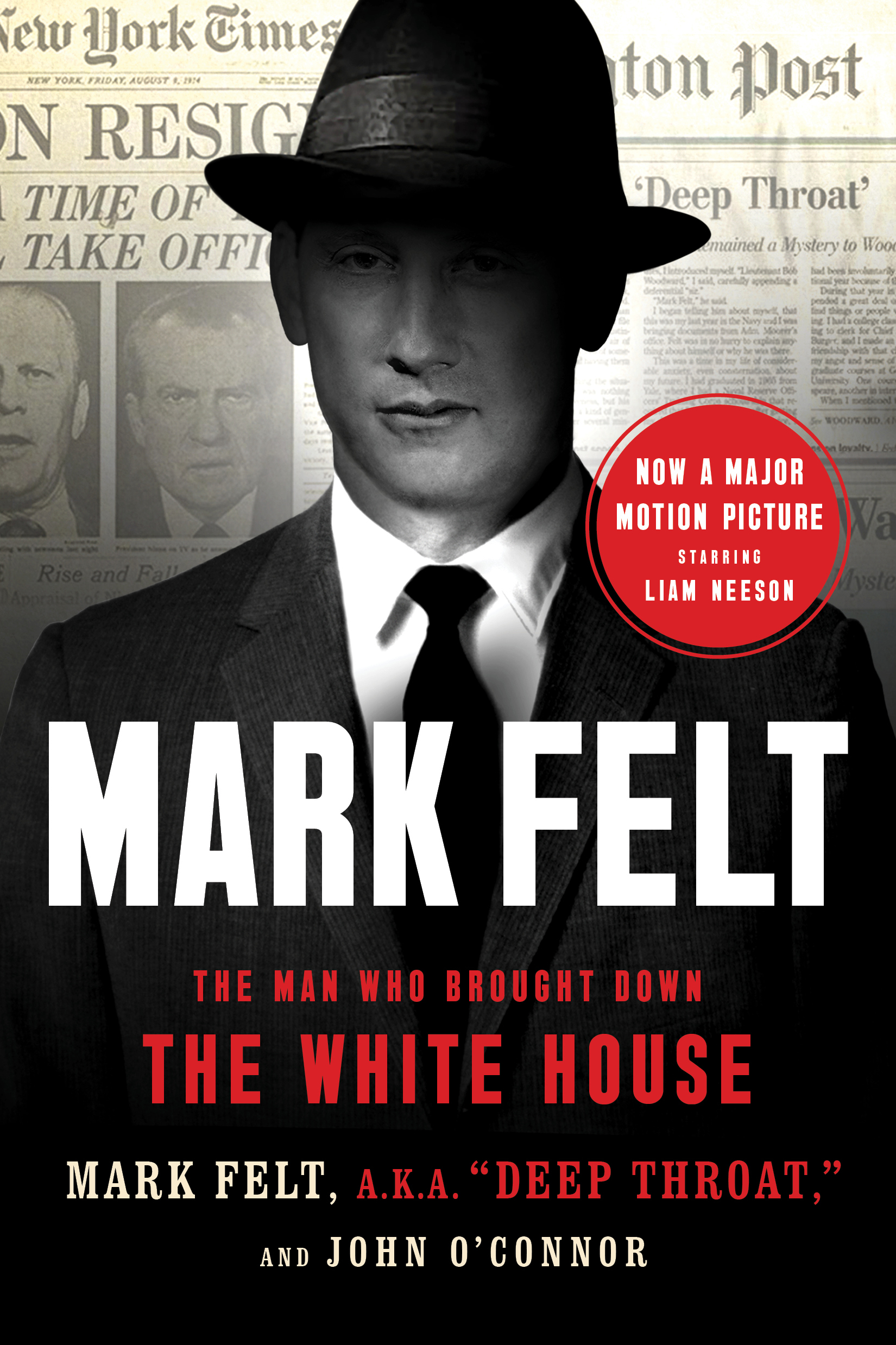

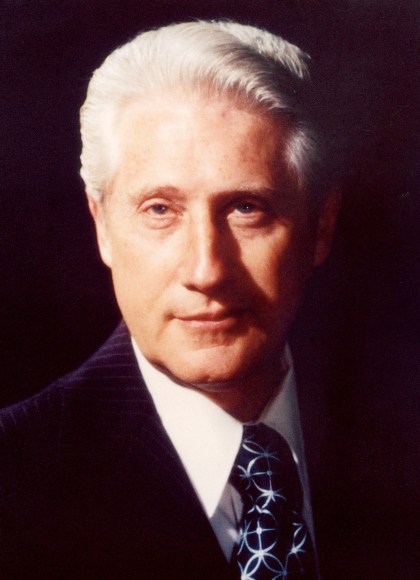

Mark Felt

The Man Who Brought Down the White House

Contributors

By Mark Felt

By John O’Connor

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook (Media Tie-In) $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback (Media Tie-In) $17.99 $23.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 26, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This absorbing account of Felt’s FBI career, from the end of the great American crime wave through World War II, the culture wars of the 1960s, and his conviction for his role in penetrating the Weather Underground, provides a rich historical and personal context to the “Deep Throat” chapter of his life. It also provides Felt’s personal recollections of the Watergate scandal, which he wrote in 1982 and kept secret, in which he explains how he came to feel that the FBI needed a “Lone Ranger” to protection it from White House corruption. Much more than a Watergate procedural, A G-Man’s Life is about life as a spy, the culture of the FBI, and the internal political struggles of mid-20th century America.

Only as he neared the end of his life did Felt confide his role in our national history to members of his family, who then shared it with their lawyer, John O’Connor. The answers to the questions Who is Mark Felt? And why did he risk so much for his country? are brilliantly answered in A G-Man’s Life.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 26, 2017

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541788398

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use