By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

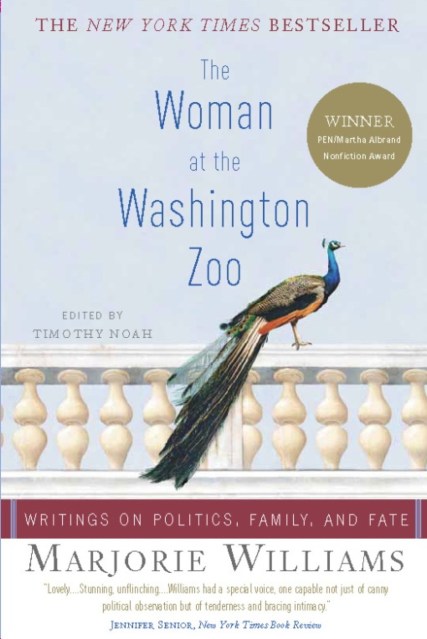

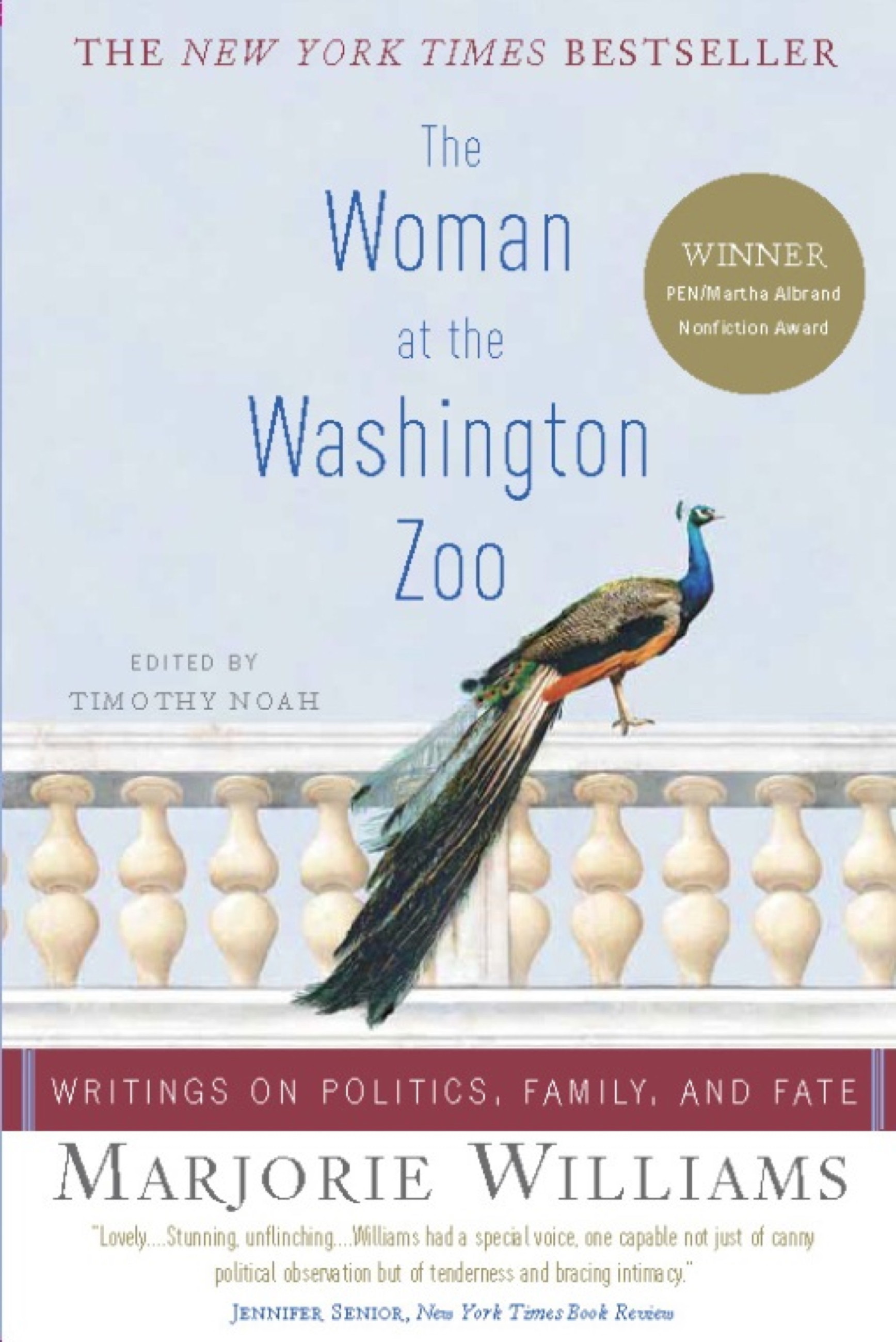

The Woman at the Washington Zoo

Writings on Politics, Family, and Fate

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 31, 2007

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586485412

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 31, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Williams also penned a weekly column for the Post’s op-ed page and epistolary book reviews for the online magazine Slate. Her essays for these and other publications tackled subjects ranging from politics to parenthood. During the last years of her life, she wrote about her own mortality as she battled liver cancer, using this harrowing experience to illuminate larger points about the nature of power and the randomness of life.

Marjorie Williams was a woman in a man’s town, an outsider reporting on the political elite. She was, like the narrator in Randall Jarrell’s classic poem, “The Woman at the Washington Zoo,” an observer of a strange and exotic culture. This splendid collection — at once insightful, funny and sad — digs into the psyche of the nation’s capital, revealing not only the hidden selves of the people that run it, but the messy lives that the rest of us lead.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use