Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

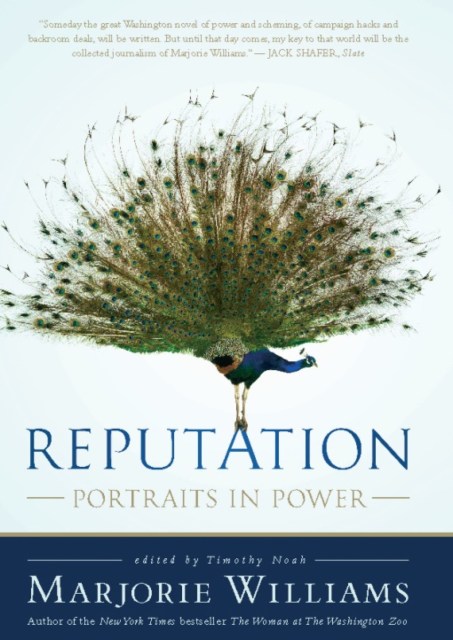

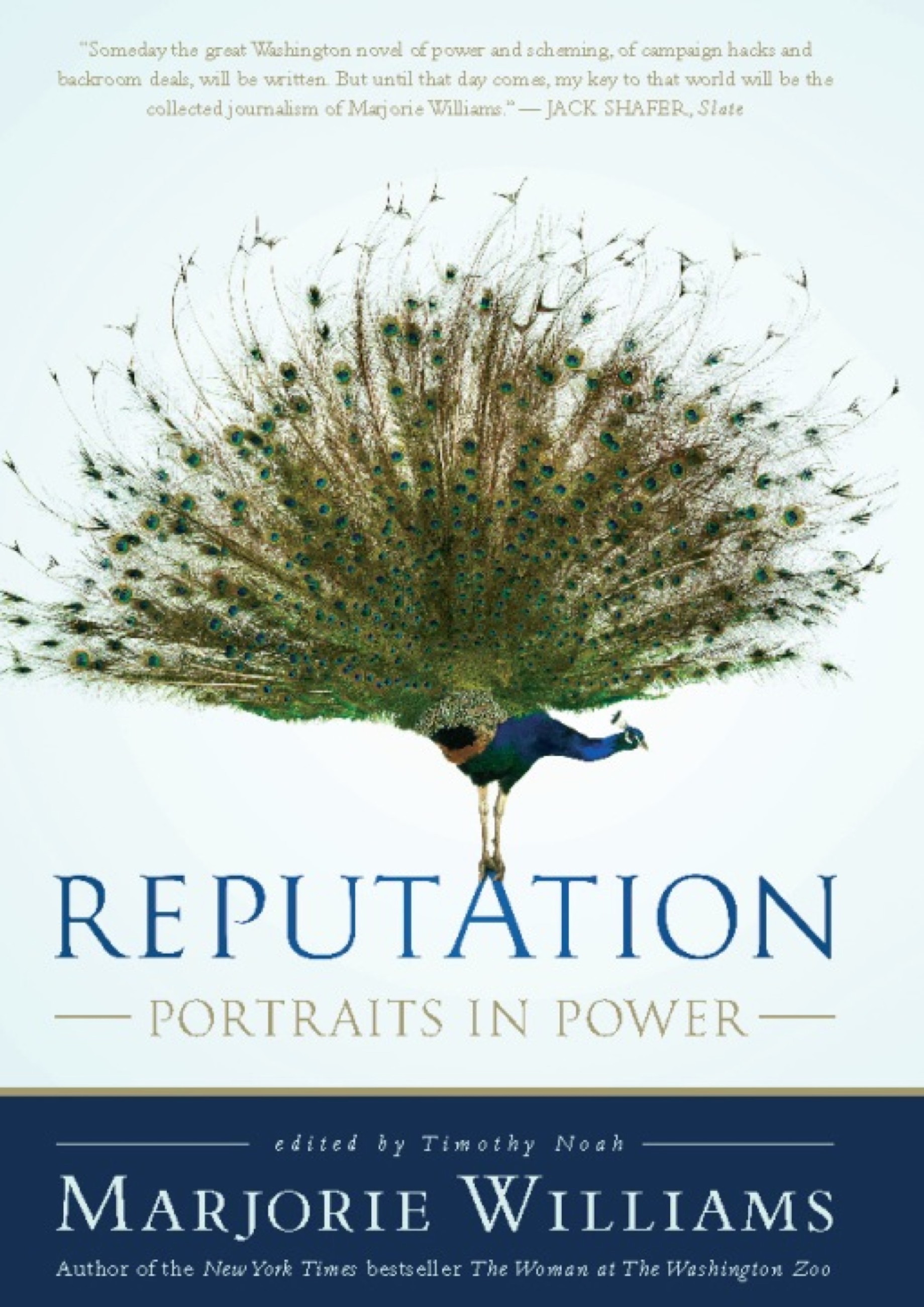

Reputation

Portraits in Power

Contributors

Edited by Timothy Noah

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 20, 2008

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786726554

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 20, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Now, in a collection of profiles with the richness of short fiction, Williams limns the personalities that dominated politics and the media during the final years of the twentieth century. In these pages, Clark Clifford grieves “in his laborious baritone” a bank scandal’s blow to his re-pu-taaaaaay-shun. Lee Atwater likens himself to Ulysses and pleads, “Tah me to the mast!” Patricia Duff sheds “precipitous tears” over her divorce from Ronald Perelman, resembling afterwards “a garden refreshed by spring rain.”

Reputation illuminates our recent past through expertly drawn portraits of powerful — and messily human — figures.