Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

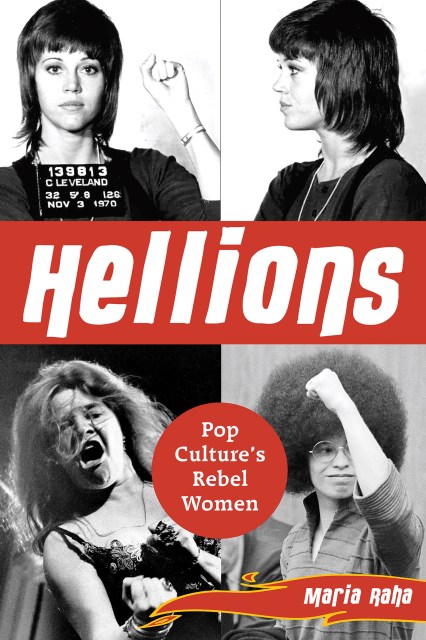

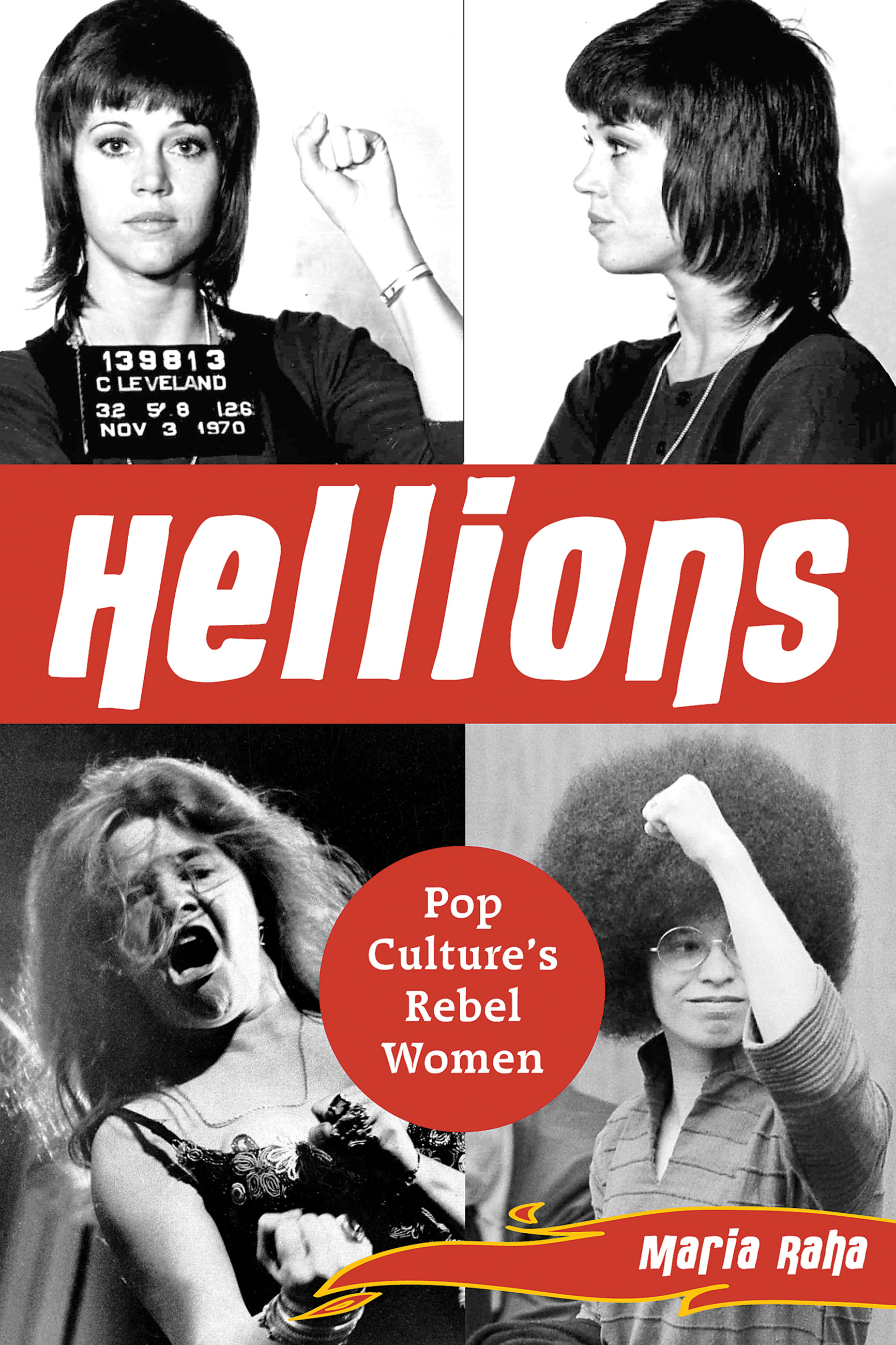

Hellions

Pop Culture's Rebel Women

Contributors

By Maria Raha

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 20, 2008

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786726264

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $10.99 $13.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 20, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Who is the iconic rebel? Is it a character from the legacy of James Dean or Clint Eastwood, or maybe a Beat Generation writer? Is it a woman?

Modern pop culture and the media have distorted the notion of rebellion. Classic male rebels appear sexy, nomadic—naturally rebellious—while unorthodox women are reprimanded, made to fit unrealistic roles and body images, or mocked for their decadence and self-indulgence. In order to appreciate our legacy of female rebels—and create space for future cultural icons—the notion rebellion needs to be revaluated.

From Madonna and Marilyn Monroe to the reality TV stars and hotel chain heiresses of the twenty-first century, Hellions analyzes the celebration of pop culture icons and its impact on notions of gender. Looking at these past examples, Hellions expands upon the definition of rebellion and offers a new understanding of what would be considered rebellious in the celebrity-obsessed media culture of the twenty-first century.

Modern pop culture and the media have distorted the notion of rebellion. Classic male rebels appear sexy, nomadic—naturally rebellious—while unorthodox women are reprimanded, made to fit unrealistic roles and body images, or mocked for their decadence and self-indulgence. In order to appreciate our legacy of female rebels—and create space for future cultural icons—the notion rebellion needs to be revaluated.

From Madonna and Marilyn Monroe to the reality TV stars and hotel chain heiresses of the twenty-first century, Hellions analyzes the celebration of pop culture icons and its impact on notions of gender. Looking at these past examples, Hellions expands upon the definition of rebellion and offers a new understanding of what would be considered rebellious in the celebrity-obsessed media culture of the twenty-first century.