By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

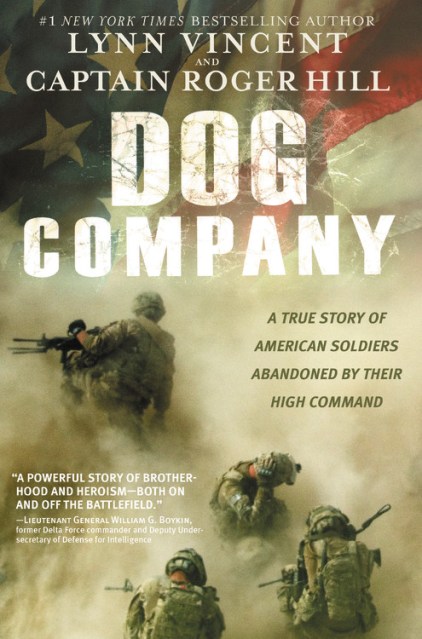

Dog Company

A True Story of American Soldiers Abandoned by Their High Command

Contributors

By Lynn Vincent

By Roger Hill

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 1, 2018

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781455516230

Price

$24.99Price

$31.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 1, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Now with a forward by Sean Hannity, this powerful story of brotherhood, bravery, and patriotism exposes the true stories behind some of the Army’s darkest secrets.

This very system ambushed Captain Roger Hill and his men.

Hill, a West Point grad and decorated combat veteran, was a rising young officer who had always followed the letter of the military law. In 2007, Hill got his dream job: infantry commander in the storied 101st Airborne. His new unit, Dog Company, 1-506th, had just returned stateside from the hell of Ramadi. The men were brilliant in combat but unpolished at home, where paperwork and inspections filled their days.

With tough love, Hill and his First Sergeant, an old-school former drill instructor named Tommy Scott, turned the company into the top performers in the battalion.

Hill and Scott then led Dog Company into combat in Afghanistan, where a third of their men became battlefield casualties after just six months. Meanwhile, Hill found himself at war with his own battalion commander, a charismatic but difficult man who threatened to relieve Hill at every turn. After two of his men died on a routine patrol, Hill and a counterintelligence team busted a dozen enemy infiltrators on their base in the violent province of Wardak. Abandoned by his high command, Hill suddenly faced an excruciating choice: follow Army rules the way he always had, or damn the rules to his own destruction and protect the men he’d grown to love.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use