Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

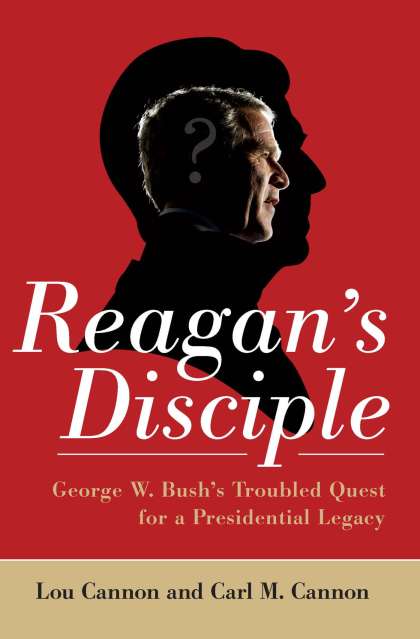

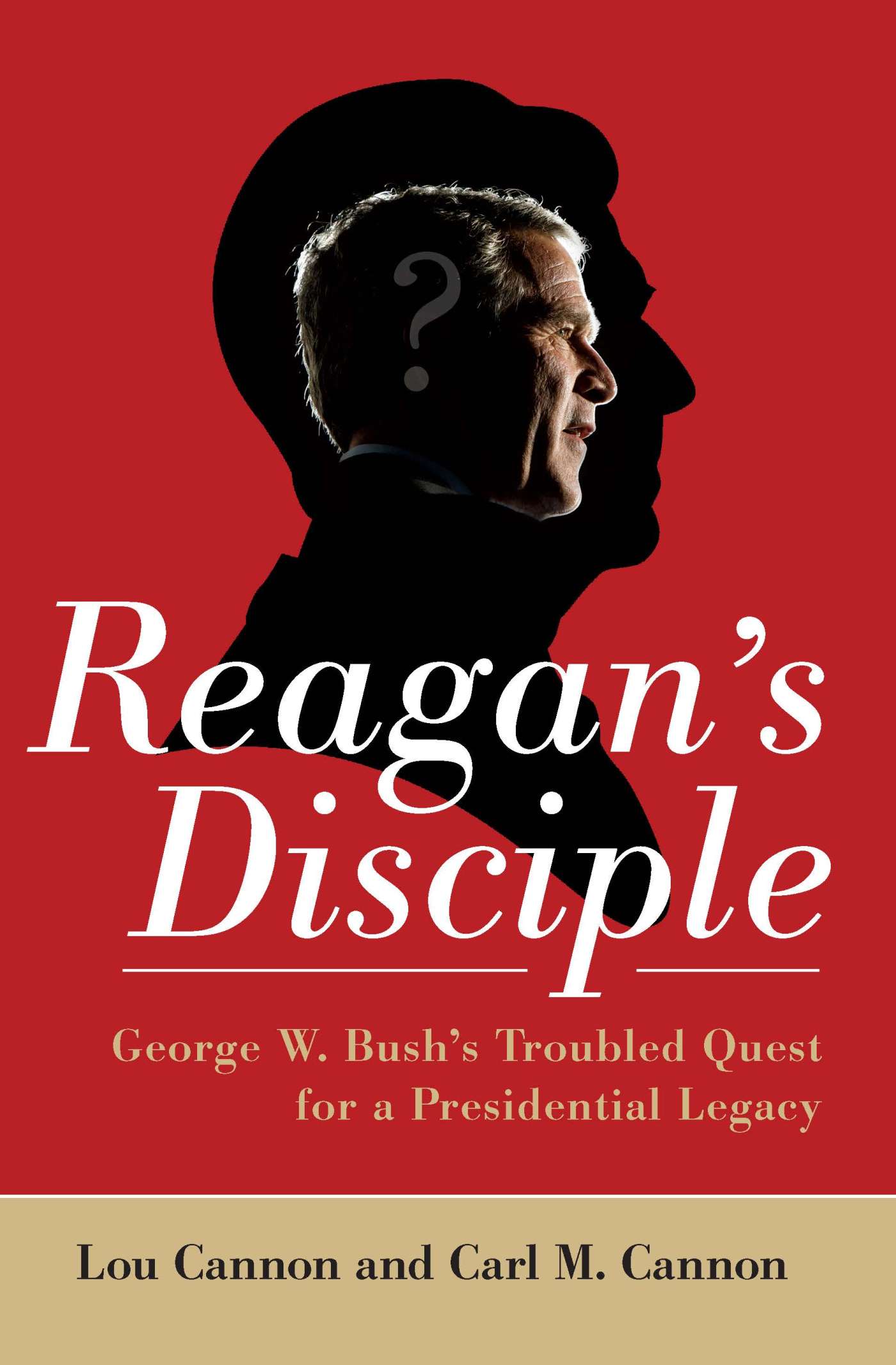

Reagan’s Disciple

George W. Bush's Troubled Quest for a Presidential Legacy

Contributors

By Lou Cannon

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 7, 2007

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586486297

Price

$20.99Price

$26.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $20.99 $26.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 7, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Reagan’s Disciple, two widely respected reporter/ historians provide an authoritative and concise investigation into these issues. They describe the essence of the 40th and the 43rd presidencies, and compare them to shed new light on the history of the past three decades. They show both how extraordinary a leader Reagan was, and how preposterous the expectations for Bush were from the beginning. As Americans look toward choosing a new leader in 2008, Reagan’s Disciple will serve as an instructive tale for Republicans, Democrats, and independents alike.