By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

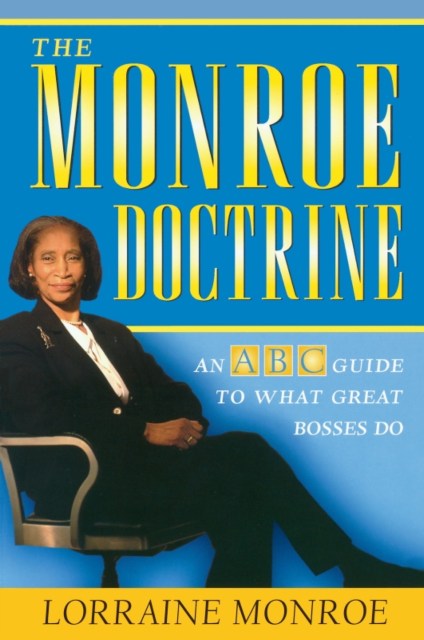

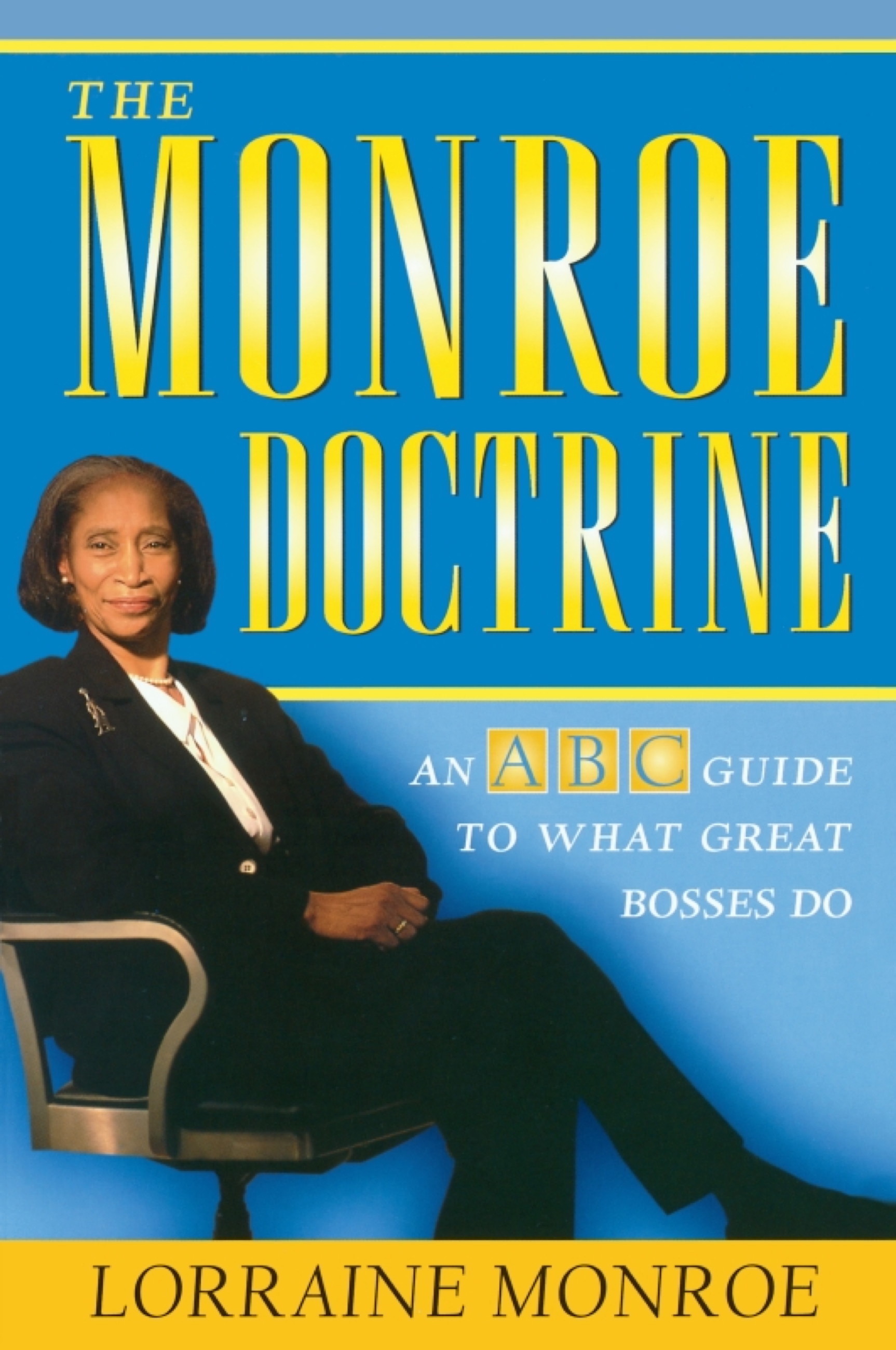

The Monroe Doctrine

An ABC Guide To What Great Bosses Do

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 21, 2003

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786725151

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 21, 2003. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Monroe Doctrine offers readers concrete lessons in the craft of leadership. Its brief, catchy lessons and anecdotes will help potential leaders tap into their natural gifts and harness those gifts to lead seemingly by instinct. Monroe’s personal story of conquering the most overwhelming challenges will inspire leaders of all types to try new ideas to enrich their lives and the lives of their organizations. With The Monroe Doctrine by their side, readers will be able to lead any organization — whether a hospital, a house of worship, a sorority, a family, a school, or a business — with renewed passion and results.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use