By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

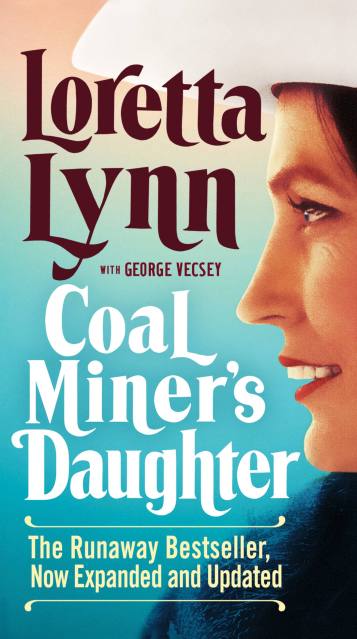

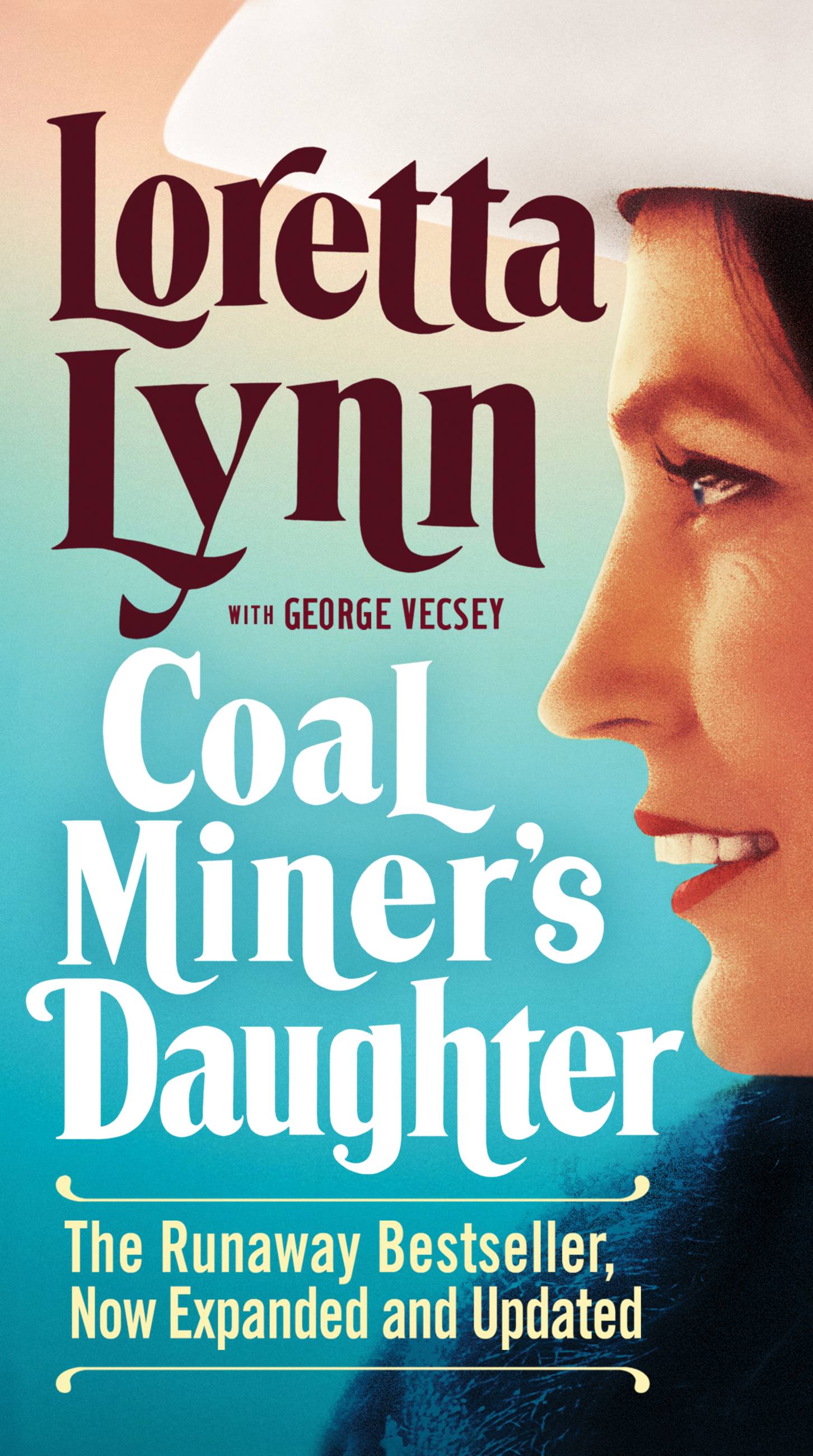

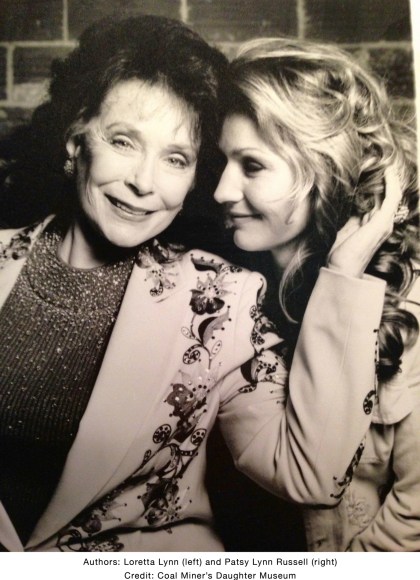

Coal Miner’s Daughter

Contributors

By Loretta Lynn

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 16, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538701690

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Mass Market $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 16, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Reissued for the 40th Anniversary of the Oscar-winning, Sissy Spacek-starring film of the same name, Coal Miner's Daughter recounts Loretta Lynn's astonishing journey to become one of the original queens of country music. Loretta grew up dirt poor in the mountains of Kentucky, she was married at thirteen years old, and became a mother soon after. At the age of twenty-four, her husband, Doo, gave her a guitar as an anniversary present.

Soon, she began penning songs and singing in front of honky-tonk audiences, and, through years of hard work, talent, and true grit, eventually made her way to Nashville, the Grand Ole Opry, eventually securing her place in country music history. Loretta's prolific and influential songwriting made her the first woman to receive a gold record in country music, and got her named the first female Entertainer of the Year by the Country Music Association. This riveting memoir introduces readers to all the highs and lows on her road to success and the tough, smart, funny, and fascinating woman behind the legend.

Soon, she began penning songs and singing in front of honky-tonk audiences, and, through years of hard work, talent, and true grit, eventually made her way to Nashville, the Grand Ole Opry, eventually securing her place in country music history. Loretta's prolific and influential songwriting made her the first woman to receive a gold record in country music, and got her named the first female Entertainer of the Year by the Country Music Association. This riveting memoir introduces readers to all the highs and lows on her road to success and the tough, smart, funny, and fascinating woman behind the legend.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use