Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

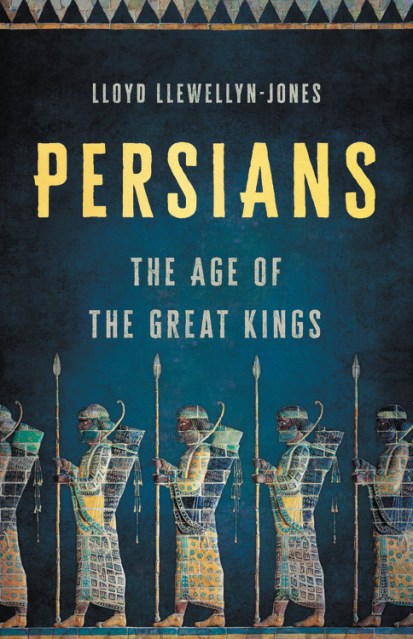

Persians

The Age of the Great Kings

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 12, 2022

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541600348

Price

$35.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 12, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Achaemenid Persian kings ruled over the largest empire of antiquity, stretching from Libya to the steppes of Asia and from Ethiopia to Pakistan. From the palace-city of Persepolis, Cyrus the Great, Darius, Xerxes, and their heirs reigned supreme for centuries until the conquests of Alexander of Macedon brought the empire to a swift and unexpected end in the late 330s BCE.

In Persians, historian Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones tells the epic story of this dynasty and the world it ruled. Drawing on Iranian inscriptions, cuneiform tablets, art, and archaeology, he shows how the Achaemenid Persian Empire was the world’s first superpower—one built, despite its imperial ambition, on cooperation and tolerance. This is the definitive history of the Achaemenid dynasty and its legacies in modern-day Iran, a book that completely reshapes our understanding of the ancient world.

Genre:

-

“In his effort to give ‘ear to a genuine ancient Persian voice,’ Llewellyn-Jones synthesizes what can be gleaned from artifacts, inscriptions and fragmentary accounts… The dead, Llewellyn-Jones argues convincingly, have been snubbed long enough.”Wall Street Journal

-

“A gripping and more Persian-centric story…Llewellyn-Jones is very good at righting the record.”Sunday Times

-

“A lively and highly readable revisionist history of the rule of the Persian ‘Great Kings.’”Literary Review

-

“Meticulously researched, Persians tells the extraordinary story of this superpower of the ancient world. In a narrative that stretches back thousands of years and across vast stretches of land, Professor Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones presents a skillful and engaging history of the Achaemenid dynasty.”All About History

-

“There is a long legacy of misinformation around ancient Persian empires, the lives of its leaders, and greater Persian society. However, by examining the artifacts and monuments that remain, historian Llewellyn-Jones brings forth a view of ancient Persia that is rich in tradition and historical significance.”Library Journal

-

“Immersive… Llewellyn-Jones expertly illuminates the decentralized, multicultural nature of the Achaemenid empire and offers valuable perspective on the modern Middle East, where the great kings of ancient Persia still feature in Iran’s national self-image. This is a valuable contribution to the understanding of ‘history’s first great superpower.’"Publishers Marketplace

-

“A brilliant feat of resurrection, restoring to the Persian Empire the color, brilliance, and complexity that renders it one of the most fascinating and influential of ancient civilizations, and of which for so long, in most histories of antiquity, it has been bled.”Tom Holland, author of Dominion

-

"Always lively, often challenging, this is a very welcome exploration of one of the greatest empires and cultures of the ancient world. Highly recommended."Adrian Goldsworthy, author of Philip and Alexander

-

“Superb, authoritative, and compelling, a fresh history of the Persian Great Kings that combines exuberant storytelling with outstanding scholarship that is both entertaining and bracing revisionist, filled with a cast of ruthless conquerors, queens, eunuchs, and concubines that brings the Persian world blazingly to life through Persian instead of the usual Greek sources. The result is a tour de force.”Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of Jerusalem: The Biography

-

“Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones brings the men, women, and rich history of ancient Persia alive in technicolor splendor with energy, passion, and real understanding. This is immersive time travel of the highest order.”Samira Ahmed, journalist and broadcaster

-

“Persians is a wonderful introduction to the ancient world’s largest and most consequential empire. Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones is one of the foremost scholars of Achaemenid history, and he gives us a gripping account of the history of ancient Persia, tracking how a small tribal society in southwestern Iran came to be the world’s first superpower.”Touraj Daryaee, University of California, Irvine

-

“This is an engaging, pacy account of the Persian Empire which is based on a rich range of sources. Going right up to the use of Cyrus the Great in modern Iran, the ‘Persian Version’ on which Professor Lloyd-Jones focuses has much to tell us about how different cultures create history and use it to tell their stories.”Helen King, professor emerita, Classical Studies, The Open University

-

“A masterful account and evocation of the history and culture of the first true world empire.”Aidan M Dodson, Hon Professor of Egyptology, University of Bristol

-

“For too long, the world of Achaemenid Persia has been viewed through the eyes of often hostile foreigners. In this compelling investigation, Llewellyn-Jones draws on a wealth of evidence—from imposing cliff-cut inscriptions to tiny seal-rings—to reveal the Persian Version of its empire’s stirring history, far removed from the traditional stereotype. Spotlighting not just the royal dynasty but a wealth of other characters (including ambitious courtiers, a wily Egyptian administrator, a Greek slave-girl enmeshed in Persia’s great power game) he brings to vivid life a sophisticated, highly complex, tightly run society with an acute sense of its place within the cosmos, where devotion to the Truth could coexist with cruelty and violence, and imperialism with cultural and religious tolerance. Clear, convincing, and meticulously researched, Persians: The Age of the Great Kings is not just a timely reassessment of the world’s first superpower—it’s a wonderfully accessible page-turner to boot.”David Stuttard, author of A History of Ancient Greece in Fifty Lives