By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

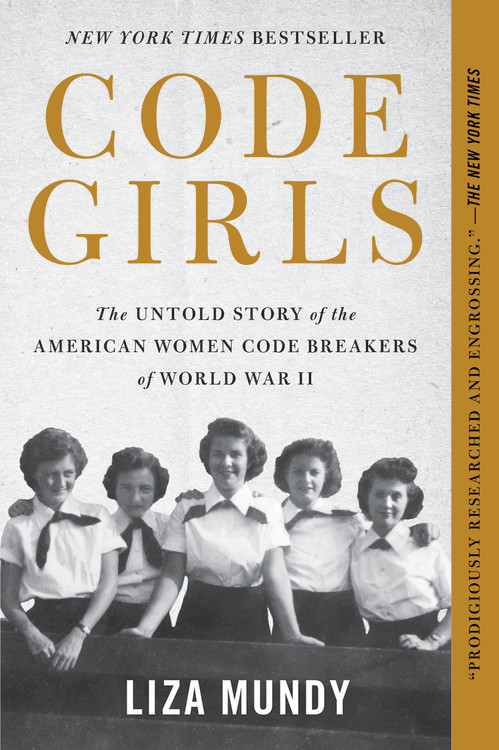

Code Girls

The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II

Contributors

By Liza Mundy

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 10, 2017

- Page Count

- 640 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316439893

Price

$49.00Price

$63.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover (Large Print) $49.00 $63.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 10, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Recruited by the U.S. Army and Navy from small towns and elite colleges, more than ten thousand women served as codebreakers during World War II. While their brothers and boyfriends took up arms, these women moved to Washington and learned the meticulous work of code-breaking. Their efforts shortened the war, saved countless lives, and gave them access to careers previously denied to them. A strict vow of secrecy nearly erased their efforts from history; now, through dazzling research and interviews with surviving code girls, bestselling author Liza Mundy brings to life this riveting and vital story of American courage, service, and scientific accomplishment.

-

"Irresistible.... We owe Mundy gratitude for rescuing these hidden figures from obscurity. Even more valuable is her challenge to the myth of the eccentric, inspired, solitary male genius, like Alan Turing."Elaine Showalter, Washington Post

-

"Code Girls...finally gives due to the courageous women who worked in the wartime intelligence community."Smithsonian.com

-

"Code Girls is a riveting account of the thousands of young coeds who flooded into Washington to help America win World War II. Liza Mundy has written a thrilling page-turner that illuminates the patriotism, rivalry, and sexism of the code-breakers' world."Lynn Povich, authorof The Good Girls Revolt

-

"Code Girls is an extraordinary book by an extraordinary author. Liza Mundy's portraits of World War II codebreakers are so skillfully and vividly drawn that I felt as if I were right there with them--mastering ciphers, outwitting the Japanese army, sinking ships, breaking hearts, and even accidentally insulting Eleanor Roosevelt. I am an evangelist for this book: You must read it."Karen Abbott, NewYork Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City and Liar,Temptress, Solider, Spy

-

"Code Girls reveals a hidden army of female cryptographers, whose work played a crucial role in ending World War II. With clarity and insight, Mundy exposes the intertwined narratives of the women who broke codes and the burgeoning field of military intelligence in the 1940s. I cannot overstate the importance of this book; Mundy has rescued a piece of forgotten history, and given these American heroes the recognition they deserve."Nathalia Holt, NewYork Times bestselling author of Rise of the Rocket Girls

-

"Mundy is a fine storyteller.... A sleek, compelling narrative.... The book is a winner. Her descriptions of codes and ciphers, how they worked and how they were broken, are remarkably clear and accessible. A well-researched, compellingly written, crucial addition to the literature of American involvement in World War II."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"Similar to Nathalia Holt's The Rise of the Rocket Girls and Margot Lee Shetterly's Hidden Figures, this is indispensable and fascinating history. Highly recommended for all readers."LibraryJournal (starred review)

-

"Mundy's fascinating book suggests that [the Code Girls'] influence did play a role in defining modern Washington and challenging gender roles--changes that still matter 75 years later."Washingtonian

-

"Fascinating.... Addictively readable.... [Mundy] displays a gift for creating both human portraits and intensely satisfying scenes."Boston Globe

-

"Like Hidden Figures, this well-crafted book reveals a remarkable slice of unacknowledged U.S. history.... Captivating."The Christian Science Monitor

-

"Extraordinary.... Mundy's book is expansive and precise. It's anecdotal enough to make it an entertaining read for the layperson, and there's plenty of technical detail to interest the crypto-nerd."Houston Chronicle

-

"Salvaging this essential piece of American military history from certain obscurity, Mundy's painstaking and dedicated research produces an eye-opening glimpse into a crucial aspect of U.S. military operations and pays overdue homage to neglected heroines of WWII. Fans of Hidden Figures (2016) and its exposé of unsung talent will revel in Mundy's equally captivating portraits of women of sacrifice, initiative, and dedication."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Astonishing.... Mundy, who mined US National Security Agency archives and interviewed survivors for the book, joins authors such as Margot Lee Shetterly and Nathalia Holt in giving the women behind great twentieth-century scientific endeavors their due."Nature

-

"Mundy unveils the untold story of a very important part of American History that otherwise would have been kept secret."Miami Herald

-

"Fans of Hidden Figures .... will love this true story of the women who cracked German and Japanese military code during World War II."Entertainment Weekly (Grade: A-)

-

"The book not only shines a light on a hidden chapter of American history, it also tells the kind of story of courage and determination that makes you want to work harder and be better."Denver Post

-

"Women who helped bring victory achieve visibility, at last, in this history."Military Times

-

"Enlightening... riveting and engaging...Liza Mundy's richly detailed account of their experiences will, hopefully, help give these dedicated and patriotic women the long overdue recognition they deserve."Finger Lakes Times

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use