By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

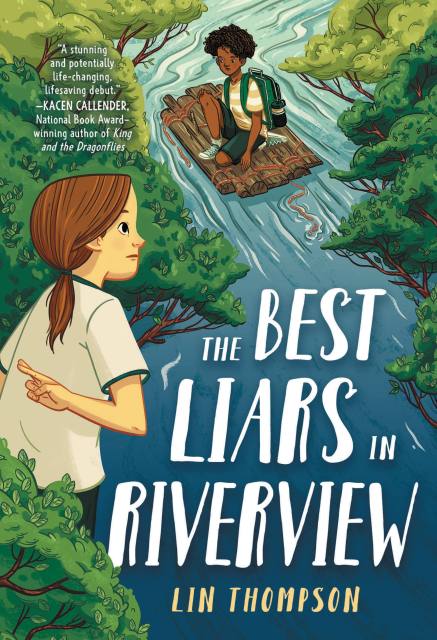

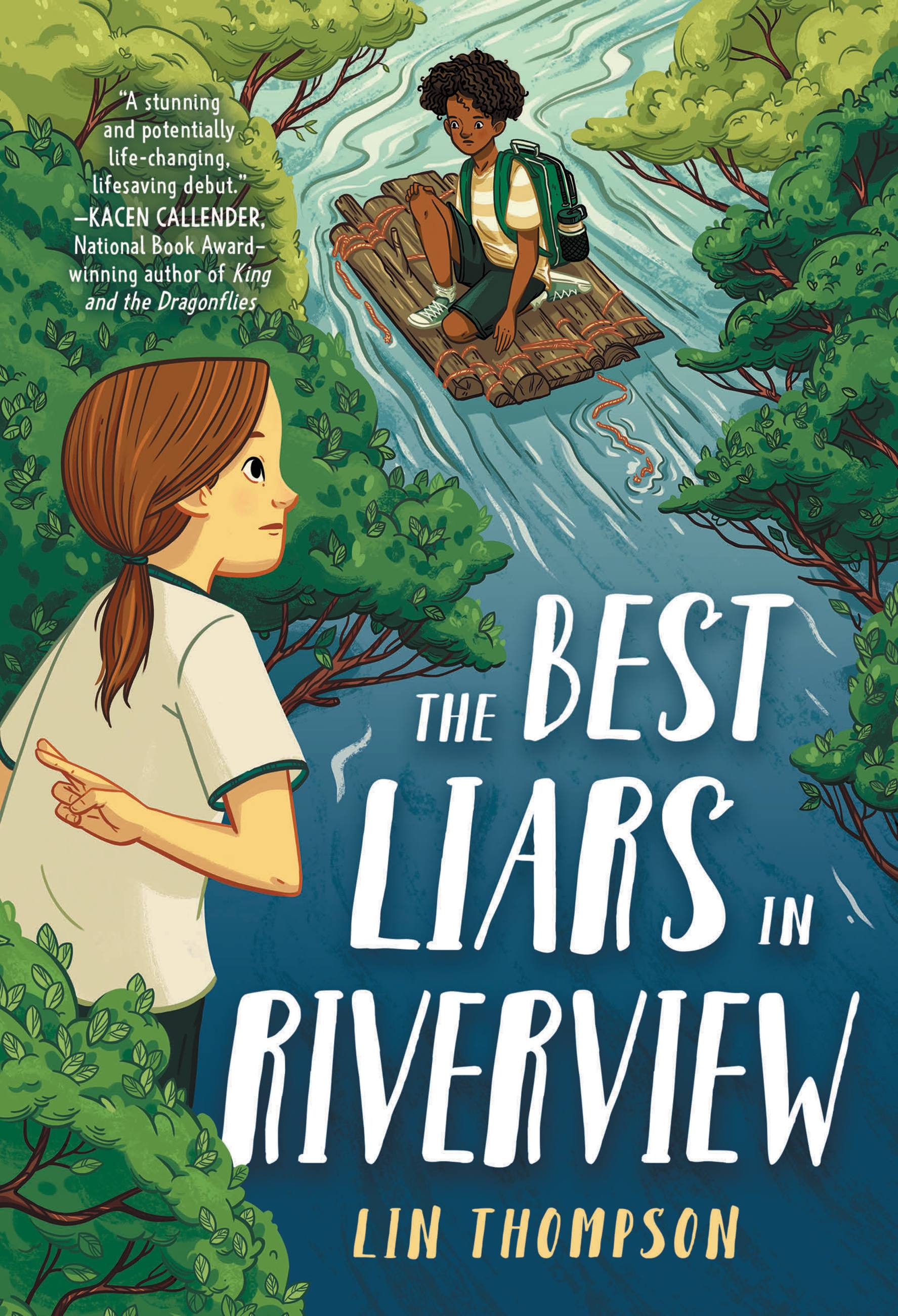

The Best Liars in Riverview

Contributors

By Lin Thompson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 8, 2022

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316276726

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $8.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 8, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Aubrey and Joel are like two tomato vines that grew along the same crooked fence: weird, yet the same kind of weird. But lately, even their shared weirdness seems weird. Then Joel disappears. Vanishes. Poof. The whole town is looking for him, and Aubrey was the last person to see Joel. Aubrey can’t say much, but since lies of omission are still lies, here’s what they know for sure:

- For the last two weeks of the school year, when sixth grade became too much, Aubrey and Joel have been building a raft in the woods.

- The raft was supposed to be just another part of their running away game.

- The raft is gone now too.

-

“The Best Liars in Riverview is a beautiful and heartwarming exploration of self-discovery. Lin Thompson writes with love and respect for their readers, and I’m excited for the young people who will have the chance to read their story. A stunning and potentially life-changing, life-saving debut.”Kacen Callender, National Book Award-winning author of King and the Dragonflies

-

"The Best Liars in Riverview is a lyrically told tale about friendship, found family, belonging and hope. Thompson has crafted a gorgeous debut that will fill an important place on LGBTQ+ shelves, and Aubrey is a character that will stay with me for a long time."Nicole Melleby, author of Hurricane Season

-

"A beautifully written, nuanced exploration of identity, The Best Liars in Riverview is heartbreaking at times in the truths it reveals about growing up and feeling different in a rural community. It also offers so much comfort and hope. Thompson's debut is a lyrical, wonderfully queer story that will forever hold a special place in my heart."A. J. Sass, author of Ana on the Edge and Ellen Outside the Lines

-

"Tender and bold all at once, Thompson's breathtaking debut about found family and identity will infuse readers with hope and courage. A luminous read."Ashley Herring Blake, Stonewall honor winner of Ivy Aberdeen's Letter to the World

-

“Don’t let the title fool you. Achingly honest and deeply moving, The Best Liars in Riverview empowers readers to seek their own truth—and live it."Lisa Jenn Bigelow, author of the Lambda Literary Award book, Hazel’s Theory of Evolution

-

“A dazzlingly atmospheric debut about truth-telling made possible through found family and self-discovery. Lin Thompson writes with heartfelt incisiveness about the pain of alienation, the preciousness of friendship, and the empowerment that comes through being seen and believed. Aubrey left an indelible mark on my heart, and their riveting story will encourage young readers everywhere to “say something” when the time is right.”Kathryn Ormsbee, author of The House in Poplar Wood

-

"A gentle and genuine coming-out story."Kirkus Reviews

-

“A sensitively written first novel…this heartfelt story shows rather than tells how friendship can lead to understanding.”Publishers Weekly

-

* “Thompson’s debut is a heartfelt coming-of-age journey that explores identity, friendship, and learning to accept who you are, even if you don’t quite understand it yet.”Booklist, starred review

-

“Thompson’s tale will have readers guessing up until the very end. A gratifying middle grade read for students who enjoy tales of adventure and belonging.”School Library Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use