By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

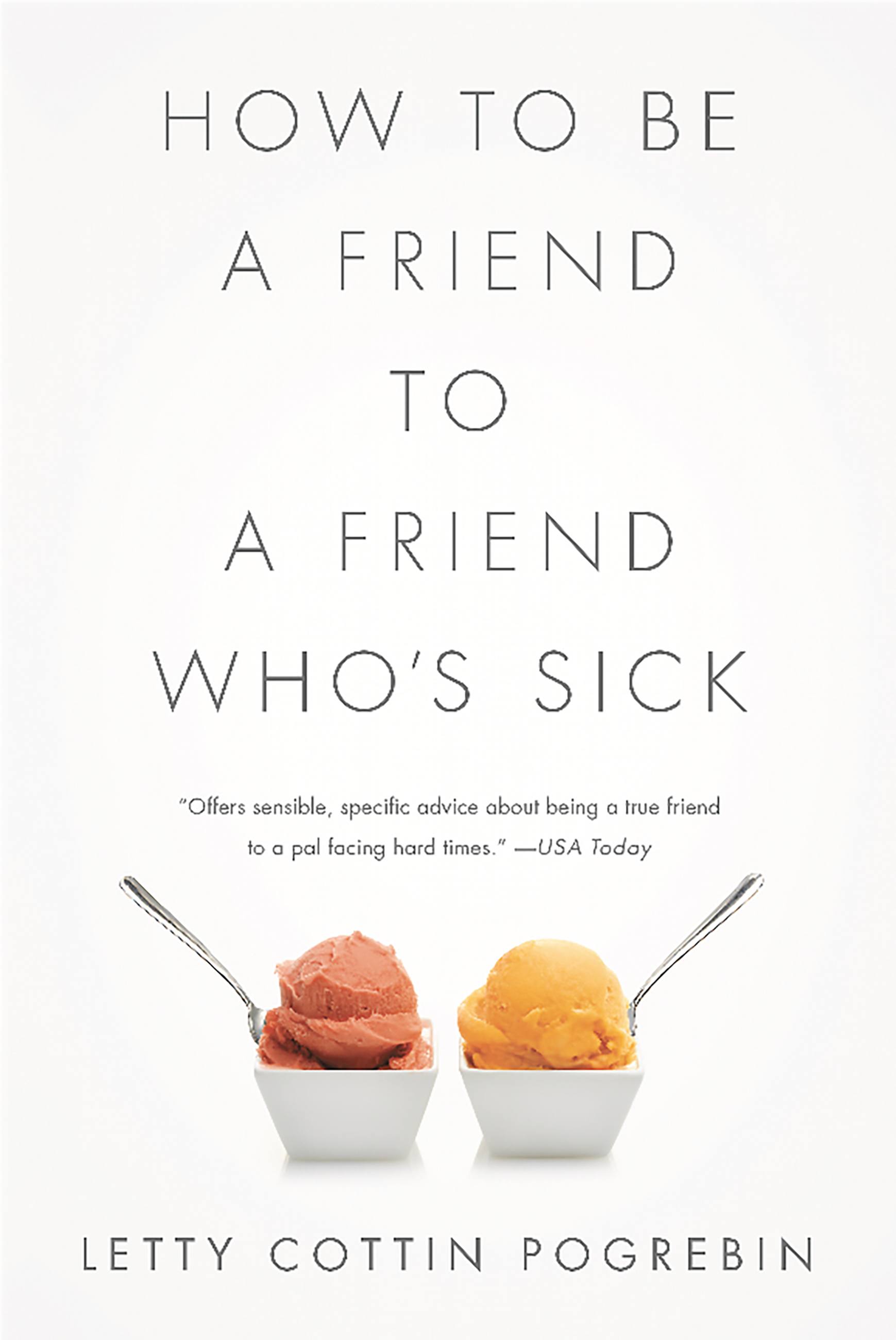

How to Be a Friend to a Friend Who’s Sick

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 5, 2014

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610393744

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 5, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Throughout her recent bout with breast cancer, Letty Cottin Pogrebin became fascinated by her friends’ and family’s diverse reactions to her and her illness: how awkwardly some of them behaved; how some misspoke or misinterpreted her needs; and how wonderful it was when people read her right. She began talking to her fellow patients and dozens of other veterans of serious illness, seeking to discover what sick people wished their friends knew about how best to comfort, help, and even simply talk to them.

Now Pogrebin has distilled their collective stories and opinions into this wide-ranging compendium of pragmatic guidance and usable wisdom. Her advice is always infused with sensitivity, warmth, and humor. It is embedded in candid stories from her own and others’ journeys, and their sometimes imperfect interactions with well-meaning friends. How to Be a Friend to a Friend Who’s Sick is an invaluable guidebook for anyone hoping to rise to the challenges of this most important and demanding passage of friendship.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use