Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

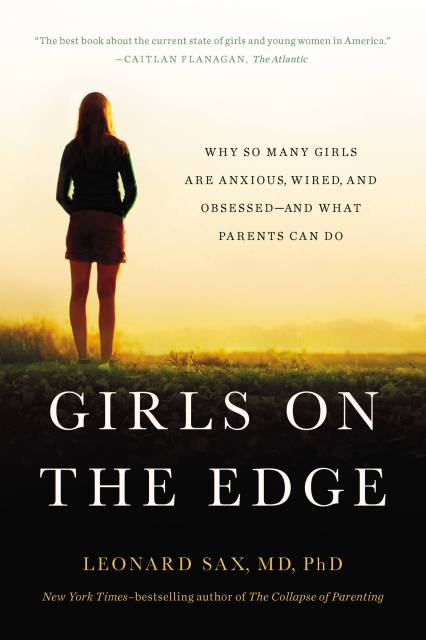

Girls on the Edge

Why So Many Girls Are Anxious, Wired, and Obsessed-And What Parents Can Do

Contributors

By Leonard Sax

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 25, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541647091

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook (New edition) $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (New edition) $24.98

- Trade Paperback (New edition) $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 25, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Girls today are motivated and hardworking. In school, they regularly outperform boys. But beneath their confident exteriors too often lies a brittle sense of self. Girls are much more likely to experience anxiety and depression than boys, and that gap is increasing.

In Girls on the Edge, physician and psychologist Leonard Sax identifies four key threats to girls’ success: sexual identity, social media, obsessions, and environmental toxins. Sax provides practical advice on how to improve the odds for your daughter. He offers tips on everything from figuring out how much time on Instagram is too much, to helping your daughter choose which sports to play, to finding female-centered activities that provide good role models and opportunities for growth.

As urgent as it is inspiring, Girls on the Edge illuminates the way to ensure our daughters grow up to be independent, confident women.

-

"The best book about the current state of girls and young women in America."Caitlin Flanagan, Atlantic

-

"Fortunately, [Leonard] Sax is up to more here than pronouncing young women irrevocably doomed.... Girls on the Edge doesn't dramatize the self-destructive behavior it describes... [and it] speaks exclusively to parents and offers concrete ways to help their daughters cultivate stronger personal identities."Slate

-

"Crucial.... Parents of tween and teen girls would do well to check this book."The Chronicle of Higher Education

-

"The world is way different from what it was a couple of years ago; this is essential reading for parents and teachers, and one of the most thought-provoking books on teen development available."Library Journal

-

"In clear, accessible language, Sax deftly blends anecdotes, clinical research, and even lines of poetry in persuasive, often fascinating chapters that speak straight to parents.... Warning that 'a 1980s solution' won't help solve twenty-first-century problems, Sax offers a holistic, sobering call to help the current generation of young women develop the support and sense of self that will allow them to grow into resilient adults."Booklist

-

"Packed with advice and concrete suggestions for parents, Girls on the Edge is a treasure trove of rarely seen research on girls, offering families guidance on some of the most pressing issues facing girls today. Dr. Sax's commitment to girls' success comes through on every page."Rachel Simmons, author of Odd Girl Out, The Curse of the Good Girl, and Enough As She Is

-

"Turn off your cell phones and computers and read this book! You will connect with your daughter in new ways, and she will thank you."Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso, author of God's Paintbrush and In God's Name

-

"Leonard Sax brings together a rare combination of psychoanalytic training with a deep empathy for girls and their stories in this important book. His argument that girls are struggling to find their centers will resonate and his recommendations for how to locate them will inspire."Courtney E. Martin, author of Perfect Girls, Starving Daughters

-

"Leonard Sax sounds a crucial warning to parents of teenage girls. No matter how attentive and savvy you are, the lives of girls today are like nothing you ever knew. The obsessions are worse, nastiness is rampant (especially on the web), drinking is up, and sexuality keeps creeping down the age ladder. 'Girls need girl-specific interventions,' Sax insists, and Girls on the Edge explains why-and also how to do it."Mark Bauerlein, PhD, professor emeritus, Emory University

-

"Dr. Sax once again combines years of experience with compelling research and common sense to intelligently challenge the status quo of what it means to raise a healthy daughter. Girls on the Edge offers skills parents can incorporate to feel more competent with our girls and young women."Florence Hilliard, director of the Gender Studies Project, University of Wisconsin-Madison

-

"I made Girls on the Edge required reading for all administrators at Woodlands Academy of the Sacred Heart, and I strongly recommend the book to all of our parents. Leonard Sax explains to parents and educators of girls just what is going on in the cyberbubble of instant messaging, texting, and social networking sites. There is a way to help girls navigate this world and find their centers-centers of genuine humanness and authenticity and, yes, spirituality. Readers will find out much they don't know, and that is more than they might guess. A must-read."Gerald J. Grossman, former head of school, Woodlands Academy of the Sacred Heart, Lake Forest, Illinois

-

"Dr. Sax's deep commitment to girls developing a positive 'sense of self' is woven into the fabric of this book. Girls on the Edge is a must-read for every parent of a girl as well as for every adult who teaches girls."Dr. Mary Seppala, former head of school, Agnes Irwin School, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania