Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

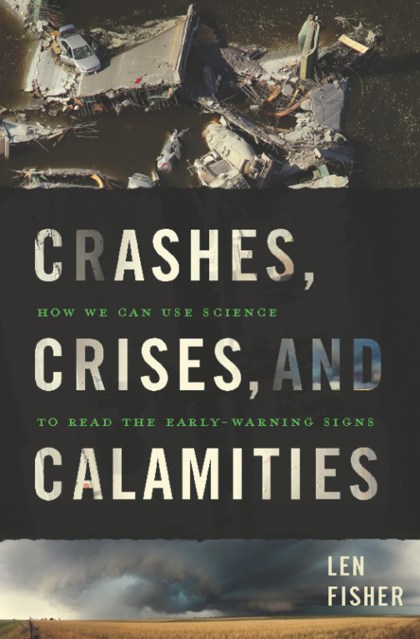

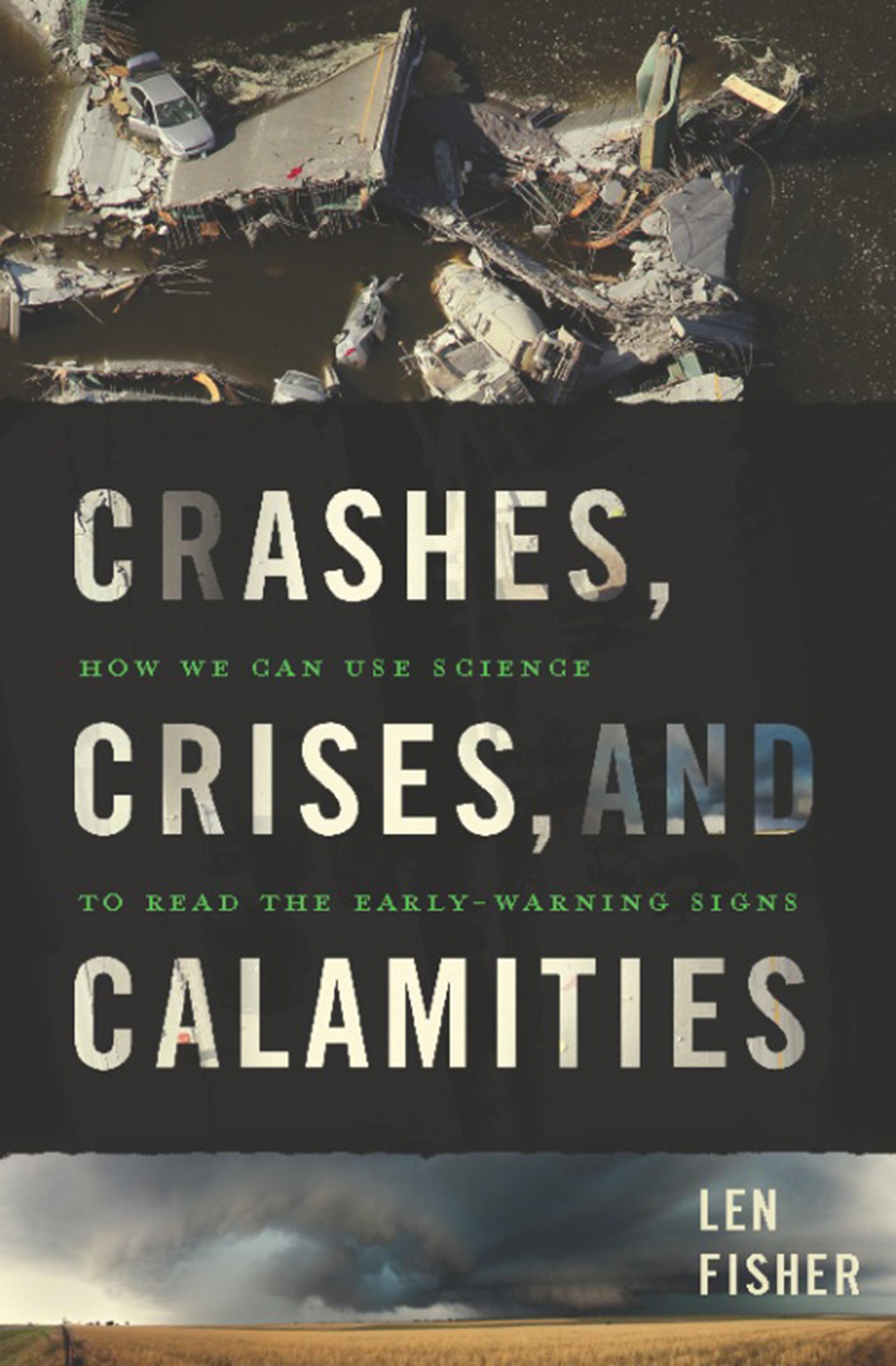

Crashes, Crises, and Calamities

How We Can Use Science to Read the Early-Warning Signs

Contributors

By Len Fisher

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 29, 2011

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465023356

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $15.99 $20.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 29, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Drawing on ecology and biology, math and physics, Crashes, Crises, and Calamities offers four fundamental tools that scientists and engineers use to forecast the likelihood of sudden change: stability, catastrophe, complexity, and game theories. In accessible prose, Len Fisher demonstrates how we can foresee and manage events that might otherwise catch us by surprise.

At the cutting edge of science, Fisher helps us find ways to act before a full-fledged catastrophe is upon us. Crashes, Crises, and Calamities is a witty and informative exploration of the chaos, complexity, and patterns of our daily lives.

Genre:

-

Scott M. Cooper, MIT Research Affiliate, co-author of Coolhunting

“With this third book in his trilogy of exploration into how to address some of society's most complex and vexing problems, Len Fisher challenges us to rethink how science and mathematics is used in what might be called ‘crisis prediction and management.' This book is getting me to rethink some of my own work.”

Simon A. Levin, Moffett Professor of Biology, Princeton University; author ofFragile Dominion

“Fisher is a master story-teller, making difficult scientific concepts seem simple through elegant exposition. Crashes, Crises, and Calamities addresses the challenge of disaster prediction in socio-economic, ecological, and physical systems by a brilliant and engaging integration of diverse scientific perspectives.”

Ian Stewart, author of Professor Stewart's Cabinet of Mathematical Curiosities

“Len Fisher is a natural storyteller, and his tales about the mathematics of crashes, crises, and calamities keep the pages turning. A great way to find out what the world's mathematicians are doing to forecast and prevent disasters of all kinds.”

Yaneer Bar-Yam, Professor and President, New England Complex Systems Institute

“Excellent discussion of the most important problem of our time.”