Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

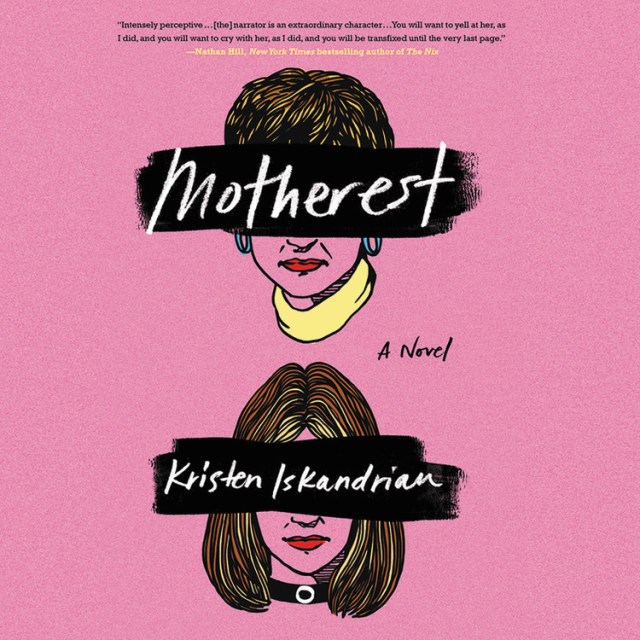

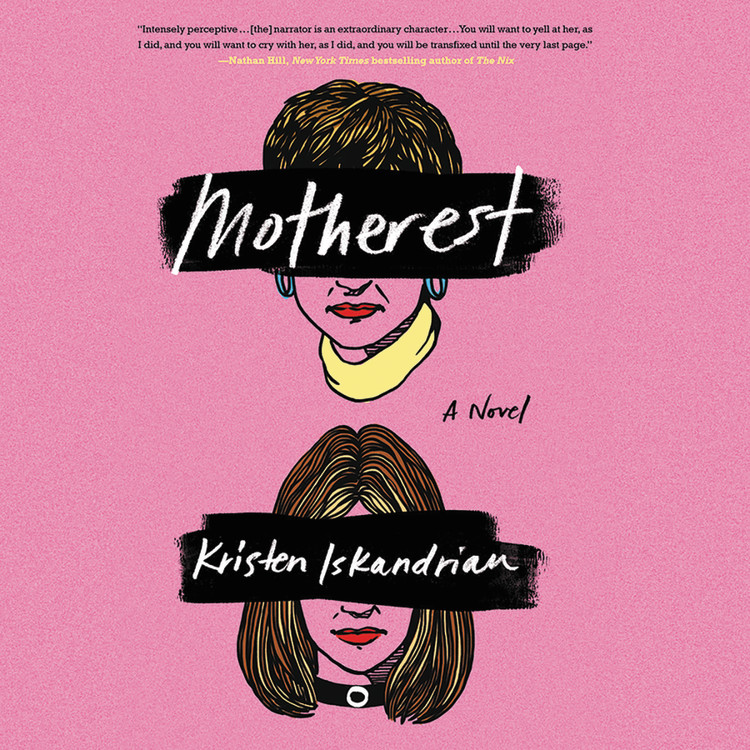

Motherest

A Novel

Contributors

Read by Lauren Fortgang

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 1, 2017

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478964056

Price

$27.99Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Hardcover $36.00 $47.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 1, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Marrying the sharp insights of Jenny Offill with the dark humor of Maria Semple, Motherest is an inventive and moving coming-of-age novel that captures the pain of fractured family life, the heat of new love, and the particular magic of the female friendship — all through the lens of a fraying daughter-mother bond.

It’s the early 1990s, and Agnes is running out of people she can count on. A new college student, she is caught between the broken home she leaves behind and the wilderness of campus life. What she needs most is her mother, who has seemingly disappeared, and her brother, who left the family tragically a few years prior.

As Agnes falls into new romance, mines female friendships for intimacy, and struggles to find her footing, she writes letters to her mother, both to conjure a closeness they never had and to try to translate her experiences to herself. When she finds out she is pregnant, Agnes begins to contend with what it means to be a mother and, in some ways, what it means to be your own mother.

It’s the early 1990s, and Agnes is running out of people she can count on. A new college student, she is caught between the broken home she leaves behind and the wilderness of campus life. What she needs most is her mother, who has seemingly disappeared, and her brother, who left the family tragically a few years prior.

As Agnes falls into new romance, mines female friendships for intimacy, and struggles to find her footing, she writes letters to her mother, both to conjure a closeness they never had and to try to translate her experiences to herself. When she finds out she is pregnant, Agnes begins to contend with what it means to be a mother and, in some ways, what it means to be your own mother.

Genre:

-

"...[A] touching, delightful, and satisfying novel about motherhood."Publishers Weekly (Best Books of 2017)

-

"MOTHEREST is a moving story of loss and loneliness and parenthood and love, in all their vast human multitudes. It's an intensely perceptive and honest novel about the sometimes-unbridgeable gap between parents and children. Kristen Iskandrian's narrator is an extraordinary character: a woman searching desperately for connection, an island trying to become a peninsula. You will want to yell at her, as I did, and you will want to cry with her, as I did, and you will be transfixed until the very last page."Nathan Hill, New York Times bestselling author of The Nix

-

"One of the most unforgettable protagonists I've read in recent years - as if a Dickens heroine was reimagined by a literary girl gang made up of Deb Olin Unferth, Katherine Dunn and Lydia Davis."Porochista Khakpour, author of The Last Illusion

-

"Kristen Iskandrian is an utterly thrilling voice, and MOTHEREST will slay you with its inventive, spiky, and heartrending investigation into the dark mysteries of family life - and the quest for a private identity within it. A smart, gorgeous, and singular debut."Laura van den Berg, author of Find Me

-

"This is a book of wombs, physical and metaphorical, an exploration into the ways we make spaces to become ourselves - both divine and misguided - and what it means to be a daughter. Kristen Iskandrian's prose is both compulsively readable and structurally unique, investigating the mysteries of human feeling through a beautiful epistolary form."Melissa Broder, author of So Sad Today

-

"I highly enjoyed MOTHEREST -- a powerful, moving, complex, wry, sensitive novel about crying, laughing, waiting, leaving, pain, loss, endurance, secrets, surprises, ambivalence, possession, parents, pregnancy, childbirth, college, home, and love."Tao Lin, author of Taipei

-

"Kristen Iskandrian has done more than write a book: she's created a world. So particular and familiar is its setting (the '90s; college), so nuanced is its narrator (broken, whip-smart, wildly perceptive and yet frozen in her own fate), and so poignant is its writing (there are poems in these paragraphs!), you'll find yourself lingering in this world long after you've turned the last page. MOTHERESTis a fresh and devastating deep dive into womanhood, motherhood, teenagehood, and grief, and is an important reminder of the aches and wonders of being alive."Molly Prentiss, author of Tuesday Nights in 1980

-

"Taut and tender, MOTHEREST one-ups the messy teenage page-turner, finding real human truths in its story of a vanished mother and a struggling daughter, a source for the sourceless longing of growing up."Amelia Gray, author of Isadora

-

"[A] stellar first novel...sharp and honest...Agnes's voice charms with a subtle undercurrent of humor and sarcasm making this a delightful and satisfying reading experience. Iskandrian is a writer to watch."Publishers Weekly (Starred Review)

-

"MOTHEREST transforms from a smart...broody meditation on abandonment into an emotionally brimming story of new life and new responsibility. It becomes saturated with hope."The Wall Street Journal

-

"[MOTHEREST forms] a tableau that is heartbreaking, hilarious, and poignant -- often at the same time. A powerfully perceptive story written with love, realism, and humor and that feels fresh despite the familiar terrain."Kirkus (Starred Review)

-

"Agnes' voice, in her heartrending letters and her funny, sad, dead-true perceptions, propels Iskandrian's brilliant debut about life's continuously shifting, perplexing intimacies."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 16.0px 'Times New Roman'; color: #212121; -webkit-text-stroke: #212121}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}Booklist