Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

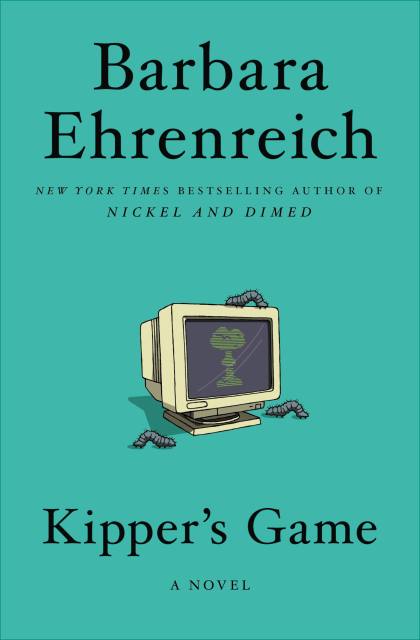

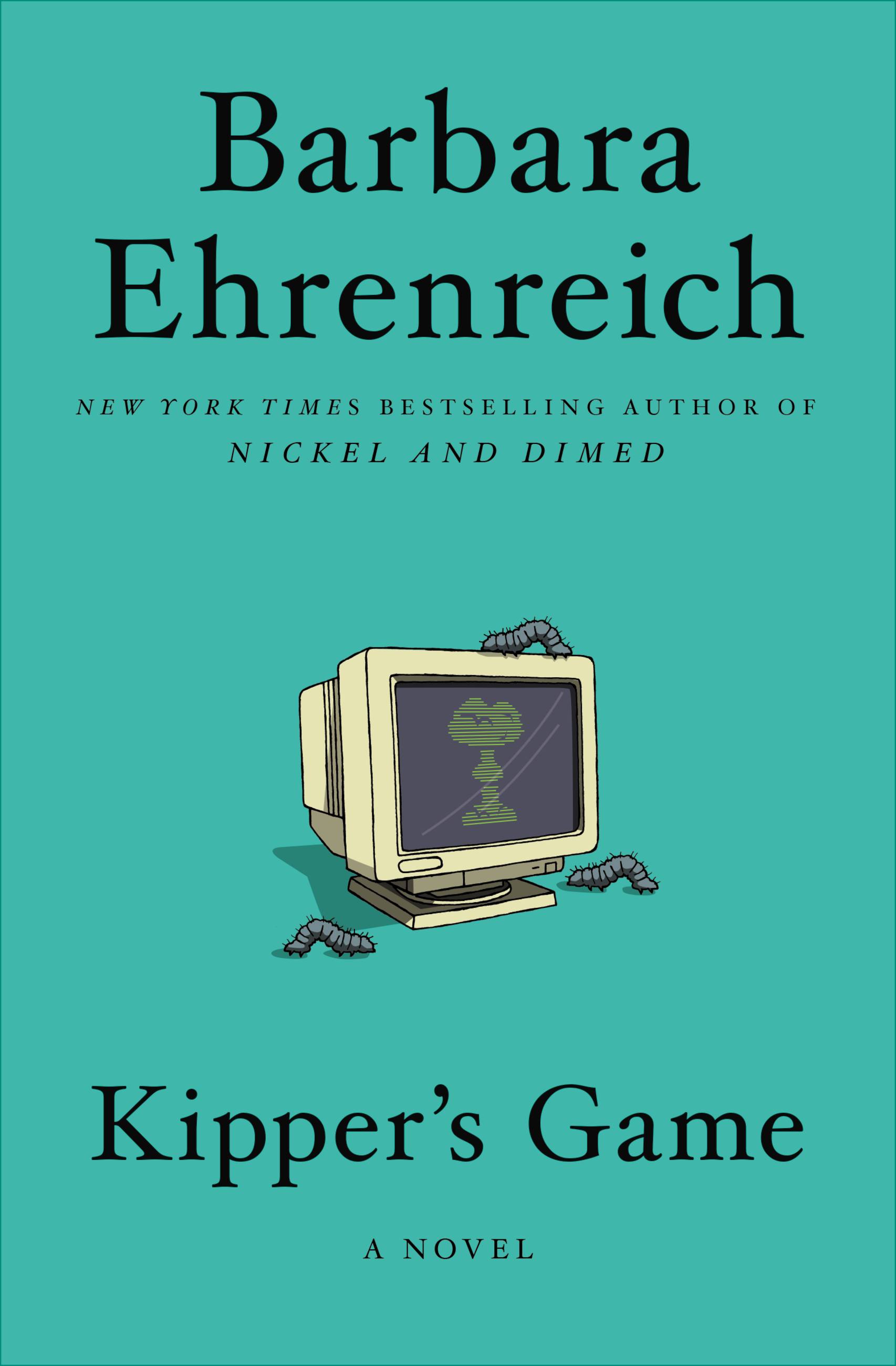

Kipper’s Game

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455543731

Price

$24.99Price

$32.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Della Markson is searching for her son, a brilliant, nihilistic computer hacker who has invented an addictive computer game. She teams up with her former professor, Alex MacBride, an academic has-been desperately in need of a publication and a drink, is looking for the papers of an obscure, long-dead neurobiologist. As they stumble through a suburban landscape littered with broken marriages and blighted careers, they discover that their personal quests are of great interest to mysterious others, and that they have been drawn into a grand design full of wondrous possibilities and perilous meanings.

For Della and Alex live in a hyper-real world of strange portents and accelerating decay. Caterpillars are destroying the trees. A cracked but eerily lucid evangelist preaches apocalypse on a pirate frequency. And in the renowned biological research institute where Della and Alex work, escaped laboratory animals roam the corridors, hazardous wastes leak unchecked, and a lethal new disease is outwitting the researchers. The search for Della’s son and Alex’s missing papers turns out to hinge on the ancient quest for the ultimate purpose of human intelligence and life.

A startling feat of the imagination from one of our sharpest social observers, Kipper’s Game is a daring and sophisticated adventure at the interface of science and metaphysics, human love and the equally human hunger for knowledge.

-

ORIGINAL PRAISE FOR KIPPER'S GAME:Entertainment Weekly

"In an intriguing fusion of subject and style...Kipper's Game splices a treatise on knowledge into a spooky-music intellectual thriller." -

"Wonderfully imaginative."Library Journal

-

"Ehrenreich...makes full use of her Ph.D. in biology to create an America on the edge of environmental ruin and anarchy--where doomsday prophets and powerful corporate entities vie for control. Complex and convincingly bleak."Kirkus