By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

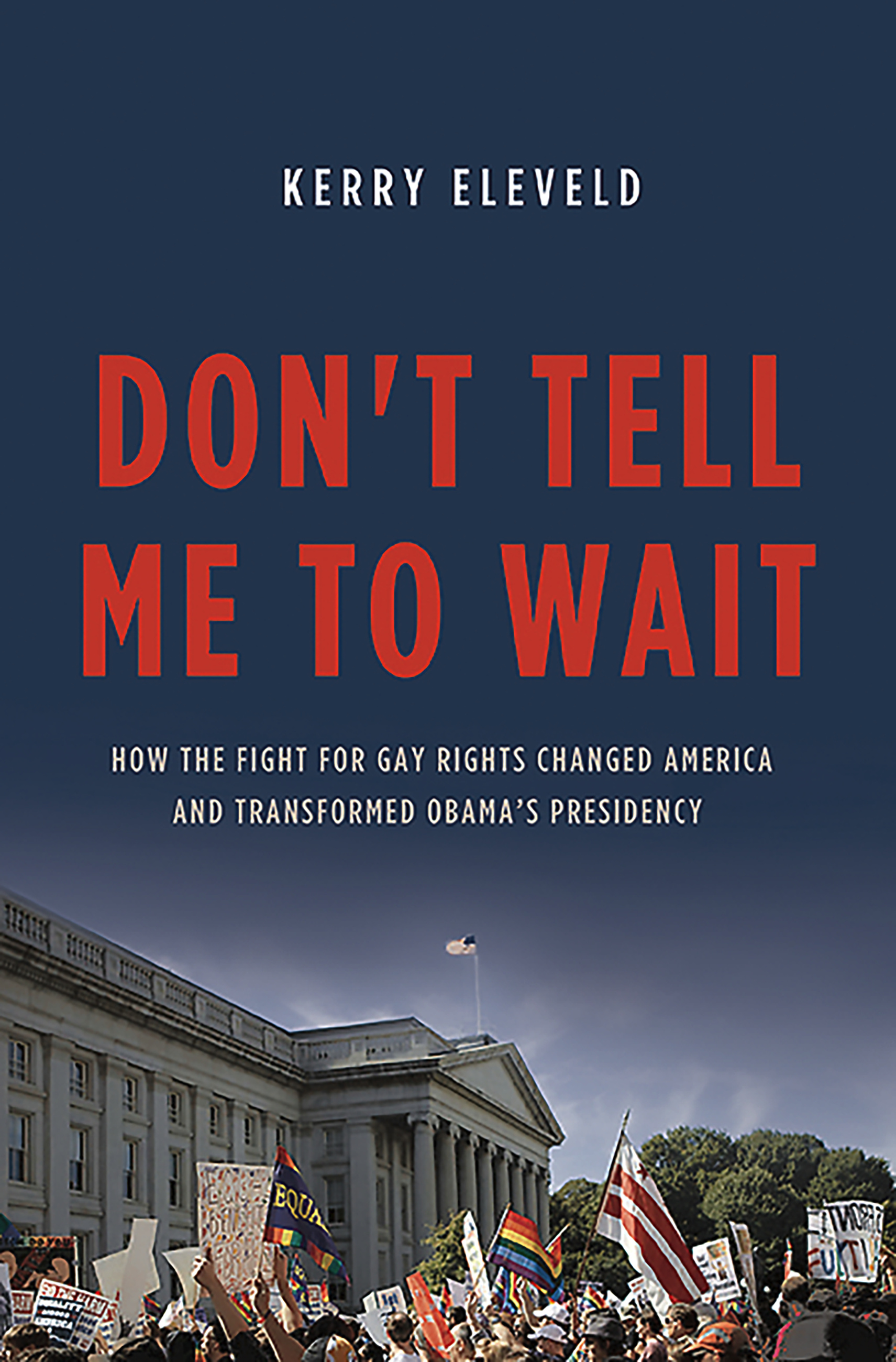

Don’t Tell Me to Wait

How the Fight for Gay Rights Changed America and Transformed Obama's Presidency

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 6, 2015

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465074891

Price

$40.00Price

$50.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 6, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Gay rights has been a defining progressive issue of Barack Obama’s presidency: Congress repealed Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell in 2010 with his strong support, and in 2011, he instructed his Justice Department to stop defending the Defense of Marriage Act, helping to pave the way for a series of Supreme Court decisions that ultimately legalized same-sex marriage nationwide. This rapid succession of victories is astonishing by any measure — and is especially incredible considering that when Obama first took office he, like many politicians, still viewed gay rights as politically toxic. In 2008, for instance, he opposed full marital rights for same-sex couples, calling marriage a “sacred union” between a man and a woman. It wasn’t until 2012, in the heat of his reelection campaign, that Obama finally embraced marriage equality.

In Don’t Tell Me to Wait, former Advocate reporter Kerry Eleveld shows that Obama’s transformation from cautious gradualist to gay rights champion was the result of intense pressure from lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender activists. These men and women changed the conversation issue by issue, pushing the president and the country toward greater freedom for LGBT Americans. Drawing on years of research and reporting, Eleveld tells the dramatic story of the fight for gay rights in America, detailing how activists pushed the president to change his mind, turned the tide of political opinion, and set the nation on course to finally embrace LGBT Americans as full citizens of this country.

With unprecedented access and unparalleled insights, Don’t Tell Me to Wait captures a critical moment in American history and demonstrates the power of activism to change the course of a presidency-and a nation.

-

"The gay rights movement accomplished the impossible in an impossibly short period of time. From deep in the trenches, Kerry Eleveld introduces us to the agitators and legal strategists who delivered the change few thought possible. Her insider account gives a new generation of activists a roadmap for achieving similar success."Markos Moulitsas, publisher, Daily Kos

-

"The gay rights movement accomplished the impossible in an impossibly short period of time. From deep in the trenches, Kerry Eleveld introduces us to the agitators and legal strategists who delivered the change few thought possible. Her insider account gives a new generation of activists a roadmap for achieving similar success."Markos Moulitsas, Publisher, Daily Kos

-

"Kerry Eleveld has written a definitive accounting of how activists, organizations, bloggers, and a handful of devoted journalists compelled the Obama administration to act on gay rights. This book tells an essential truth of progressive change: The arc of the moral universe may bend toward justice, but it does not bend on its own. It must be pushed, by we the people."David Domke, author of The God Strategy: How Religion Became A Political Weapon in America

-

"Kerry Eleveld is one of the great journalists of this generation, and she was uniquely qualified to cover its most epic civil rights battle. A spectacular writer who loves truth. This book is a riveting story filled with the passion of those that she covered over the years. An epic story told by an epic journalist. It just doesn't get any better!"David Mixner, author of Stranger Among Friends

-

"[A] smart, sharply observed book.... It's true, as Eleveld says, that [Obama] needed the activists to push, as a matter of politics. And they wrote a script for social change other movements are already studying."New York Times Book Review

-

"In the years to come, when all people remember are the victory speeches and the White House wrapped in rainbow lights, Don't Tell Me to Wait will serve as an important reminder of the truth of how the battle for equality was fought and of those who deserve the credit for the victory."Dallas Voice

-

"Eleveld brilliantly takes the reader behind the scenes of the president's evolution on LGBT equality.... While Don't Tell Me to Wait serves as a highly informative piece on how transformation actually occurs in political leadership, it also gracefully teaches us a lesson on our responsibility."AfterEllen.com

-

"[Eleveld] tells the story compellingly, with lots of insider details, and the drama political junkies love. She also conveys the urgency many felt about these topics. [Readers] will gain new perspectives from Eleveld's diligence."Library Journal

-

"[Eleveld] thoroughly tracks the president's hard-won 'evolution' in embracing the national LBGT agenda.... An accomplished chronicle of the setbacks and successes by a journalist in the trenches."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Kerry Eleveld has written a definitive accounting of how activists, organizations, bloggers, and a handful of devoted journalists compelled the Obama administration to act on gay rights. This book tells an essential truth of progressive change: The arc of the moral universe may bend toward justice, but it does not bend on its own. It must be pushed, by we the people."David Domke, author of The God Strategy: How Religion Became A Political Weapon in America

-

"Kerry Eleveld is one of the great journalists of this generation, and she was uniquely qualified to cover its most epic civil rights battle. A spectacular writer who loves truth. This book is a riveting story filled with the passion of those that she covered over the years. An epic story told by an epic journalist. It just doesn't get any better!"David Mixner, author of Stranger Among Friends