By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

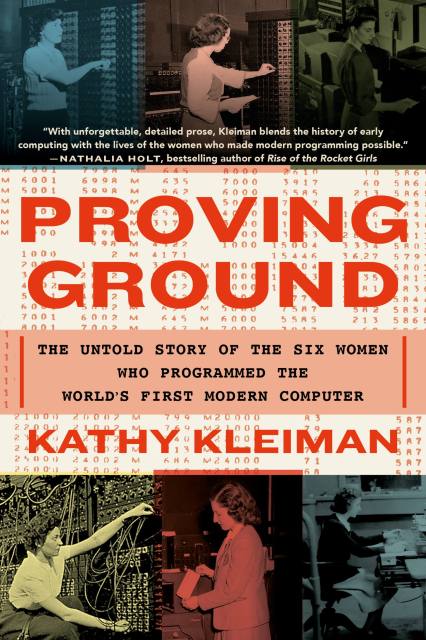

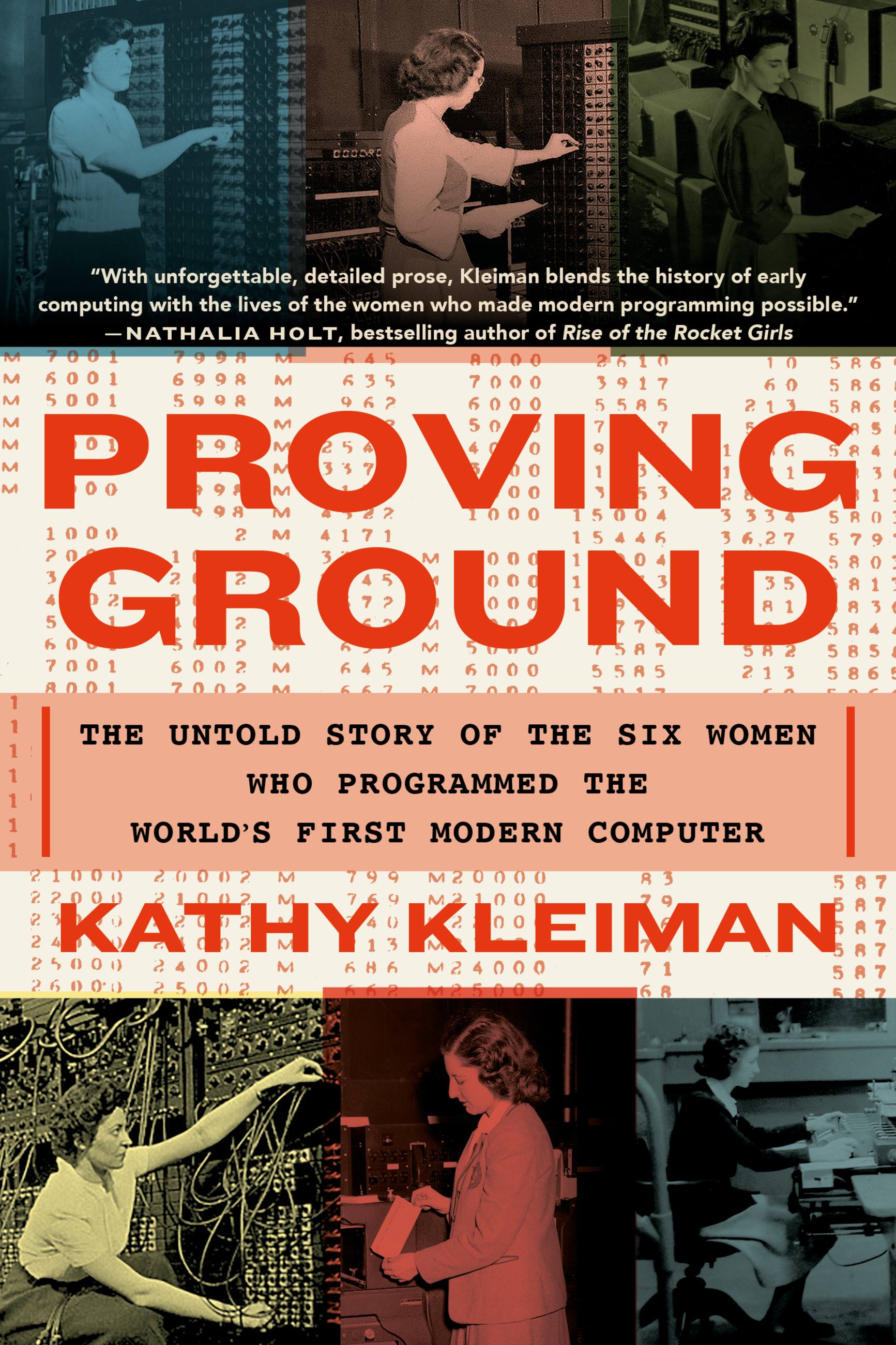

Proving Ground

The Untold Story of the Six Women Who Programmed the World’s First Modern Computer

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 26, 2022

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538718278

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 26, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

After the end of World War II, the race for technological supremacy sped on. Top-secret research into ballistics and computing, begun during the war to aid those on the front lines, continued across the United States as engineers and programmers rushed to complete their confidential assignments. Among them were six pioneering women, tasked with figuring out how to program the world's first general-purpose, programmable, all-electronic computer—better known as the ENIAC—even though there were no instruction codes or programming languages in existence. While most students of computer history are aware of this innovative machine, the great contributions of the women who programmed it were never told—until now.

Over the course of a decade, Kathy Kleiman met with four of the original six ENIAC Programmers and recorded extensive interviews with the women about their work. Proving Ground restores these women to their rightful place as technological revolutionaries. As the tech world continues to struggle with gender imbalance and its far-reaching consequences, the story of the ENIAC Programmers' groundbreaking work is more urgently necessary than ever before, and Proving Ground is the celebration they deserve.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use