By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

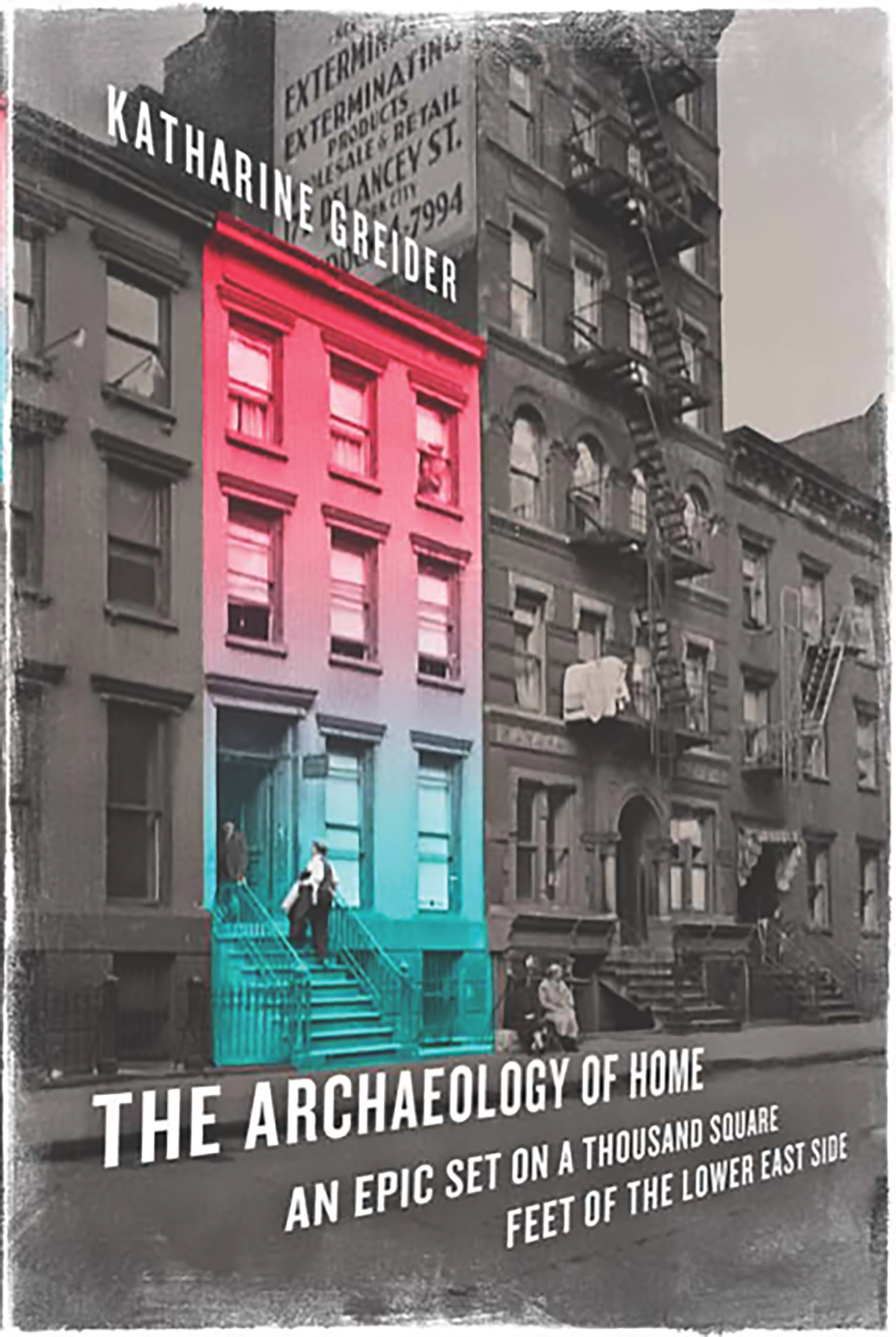

The Archaeology of Home

An Epic Set on a Thousand Square Feet of the Lower East Side

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 22, 2011

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586489908

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $17.99 $22.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 22, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

During the journey, Greider examines how people balance the need for permanence with the urge to migrate, and how the home is the resting place for ancestral ghosts. The land on which Number 239 was built has a history as long as America’s own. It provisioned the earliest European settlers who needed fodder for their cattle; it became a spoil of war handed from the king’s servant to the revolutionary victor; it was at the heart of nineteenth-century Kleinedeutschland and of the revolutionary Jewish Lower East Side. America’s immigrant waves have all passed through 7th Street. In one small house is written the history of a young country and the much longer story of humankind and the places they came to call home.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use