By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

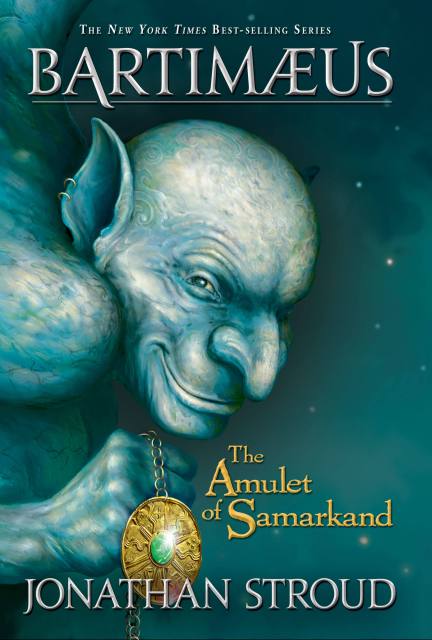

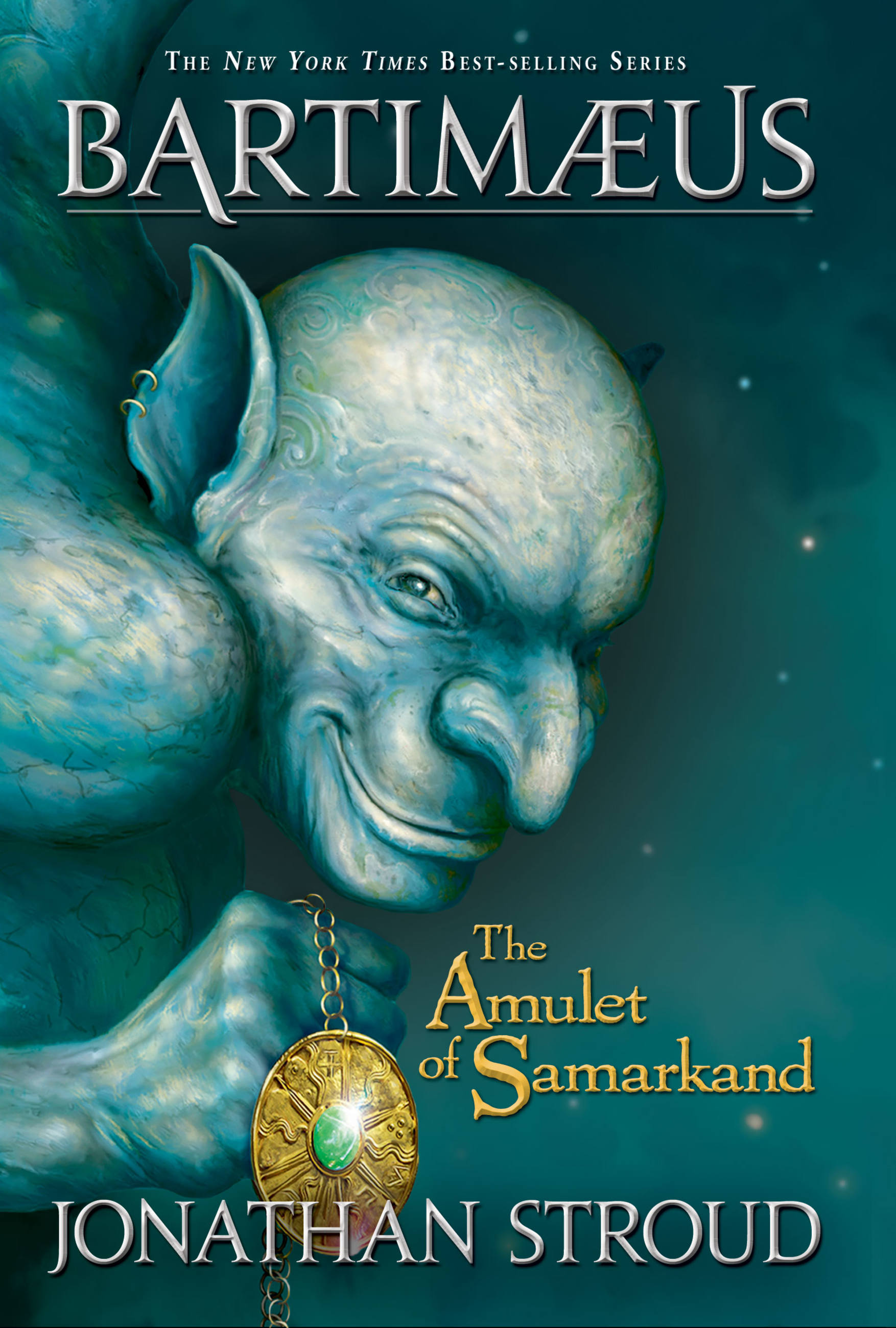

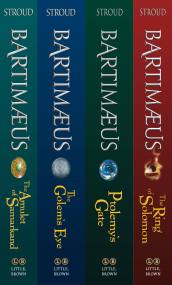

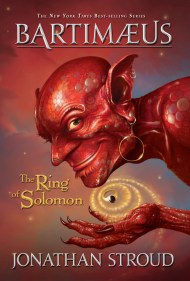

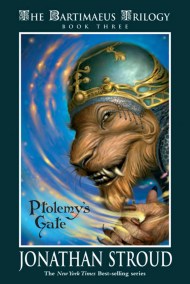

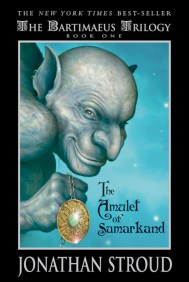

The Amulet of Samarkand

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 13, 2011

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781423141464

Prices

- Sale Price $1.99

- Regular Price $7.99

- Discount (75% off)

Prices

- Sale Price $1.99 CAD

- Regular Price $9.99 CAD

- Discount (80% off)

Format

Format:

ebook $1.99 $1.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 13, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Be careful what you wish for.

Nathaniel is a magician's apprentice, taking his first lessons in the arts of magic. But when a devious hot-shot wizard named Simon Lovelace ruthlessly humiliates Nathaniel in front of his elders, Nathaniel decides to kick up his education a few notches and show Lovelace who's boss. With revenge on his mind, he summons the powerful djinni, Bartimaeus. But summoning Bartimaeus and controlling him are two different things entirely, and when Nathaniel sends the djinni out to steal Lovelace's greatest treasure, the Amulet of Samarkand, he finds himself caught up in a whirlwind of magical espionage, murder, and rebellion.

Nathaniel is a magician's apprentice, taking his first lessons in the arts of magic. But when a devious hot-shot wizard named Simon Lovelace ruthlessly humiliates Nathaniel in front of his elders, Nathaniel decides to kick up his education a few notches and show Lovelace who's boss. With revenge on his mind, he summons the powerful djinni, Bartimaeus. But summoning Bartimaeus and controlling him are two different things entirely, and when Nathaniel sends the djinni out to steal Lovelace's greatest treasure, the Amulet of Samarkand, he finds himself caught up in a whirlwind of magical espionage, murder, and rebellion.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use