Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

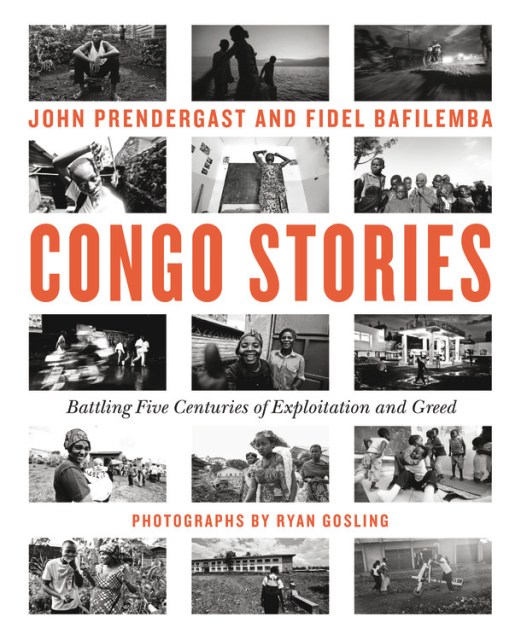

Congo Stories

Battling Five Centuries of Exploitation and Greed

Contributors

Photographs by Ryan Gosling

Foreword by Soraya Aziz Souleymane

Afterword by Chouchou Namegabe

Afterword by Dave Eggers

Illustrated by Sam Ilus

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 4, 2018

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455584642

Price

$28.00Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 4, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the author of the New York Times bestselling and award-winning Not on Our Watch, John Prendergast co-writes a compelling book with Fidel Bafilemba–with stunning photographs by Ryan Gosling–revealing the way in which the people and resources of the Democratic Republic of Congo have been used throughout the last five centuries to build, develop, advance, and safeguard the United States and Europe. The book highlights the devastating price Congo has paid for that support. However, the way the world deals with Congo is finally changing, and the book tells the remarkable stories of those in Congo and the United States leading that transformation.

The people of Congo are fighting back against a tidal wave of international exploitation and governmental oppression to make things better for their nation, their neighborhoods, and their families. They are risking their lives to resist and alter the deadly status quo. And now, finally, there are human rights movements led by young people in the United States and Europe building solidarity with Congolese change-makers in support of dignity, justice, and equality for the Congolese people. As a result, the way the world deal with Congo is finally changing.

Fidel Bafilemba, Ryan Gosling, and John Prendergast traveled to Congo to document some of the stories not only of the Congolese upstanders who are building a better future for their country but also of young Congolese people overcoming enormous odds just to go to school and help take care of their families.

Through Gosling’s photographs of Congolese daily life, Bafilemba’s profiles of heroic Congolese activists, and Prendergast’s narratives of the extraordinary history and evolving social movements that directly link Congo with the United States and Europe, Congo Stories provides windows into the history, the people, the challenges, the possibilities, and the movements that could change the course of Congo’s destiny.

Chosen by Amazon as the Best Book of the Month for December 2018 in Biographies & Memoirs, History, and Nonfiction.

Featuring the life story of Dr. Denis Mukwege, winner of the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize

The people of Congo are fighting back against a tidal wave of international exploitation and governmental oppression to make things better for their nation, their neighborhoods, and their families. They are risking their lives to resist and alter the deadly status quo. And now, finally, there are human rights movements led by young people in the United States and Europe building solidarity with Congolese change-makers in support of dignity, justice, and equality for the Congolese people. As a result, the way the world deal with Congo is finally changing.

Fidel Bafilemba, Ryan Gosling, and John Prendergast traveled to Congo to document some of the stories not only of the Congolese upstanders who are building a better future for their country but also of young Congolese people overcoming enormous odds just to go to school and help take care of their families.

Through Gosling’s photographs of Congolese daily life, Bafilemba’s profiles of heroic Congolese activists, and Prendergast’s narratives of the extraordinary history and evolving social movements that directly link Congo with the United States and Europe, Congo Stories provides windows into the history, the people, the challenges, the possibilities, and the movements that could change the course of Congo’s destiny.

Chosen by Amazon as the Best Book of the Month for December 2018 in Biographies & Memoirs, History, and Nonfiction.

Featuring the life story of Dr. Denis Mukwege, winner of the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize

-

"In this well-organized, vigorously informative, polyphonic, unnerving, and conscience-rousing presentation, [Prendergast] and researcher and activist Bafilemba trace 'the connection between natural resources exploitation and the violent conflicts' destroying the lives of millions in the Democratic Republic of Congo ... A thoughtfully assembled resource and a clarion call for readers to seek out ethically sourced goods and support efforts to bring justice and peace to this cruelly pillaged land."Booklist

-

"Eye-opening reportage from an African nation that has been robbed and despoiled for centuries-but that is now finding paths of resistance ... No thoughtful reader of this book will look at his or her computer or cellphone the same way again."Kirkus