Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

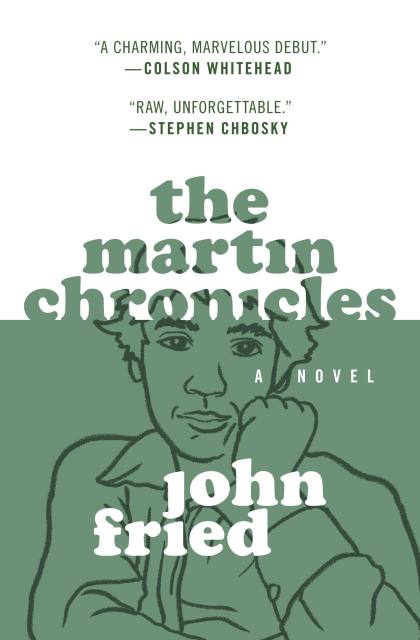

The Martin Chronicles

Contributors

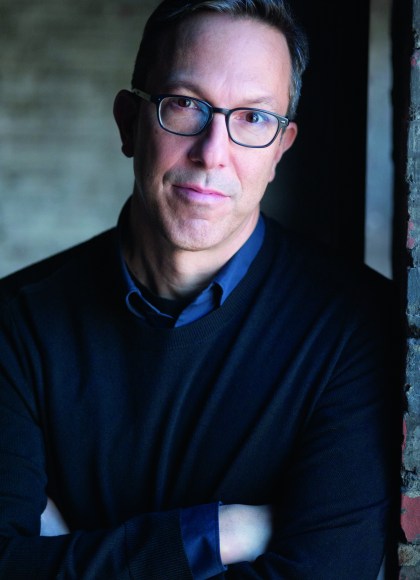

By John Fried

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 8, 2019

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538729854

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 8, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A powerful and heartfelt coming-of-age novel that follows Martin Kelso as he grows up in 1980s New York and faces the magic of first experiences, as well as the heartbreak of hard-won life lessons.

Martin Kelso's comfortable world starts to change at the age of eleven. Girls get under his skin in ways he never noticed before. His cousin Evie, who used to be Marty's closest confidante–the one who taught him the right way to eat a pizza and how to catch tadpoles–has grown up into a stranger, mysterious and unpredictable. Marty and his best friends once inhabited fantasy worlds of their own making, full of cowboys and cops and robbers, where the heroes always won the day. But now, as neighborhood kids are attacked on their walk to school, they find themselves wanting to play a new game that better prepares them for real life.

As life changes quickly and Marty feels less secure with himself, the difference between games and reality, friend and foe, and right from wrong becomes much more difficult to distinguish. At the same time, this new world offers possibilities as exciting as they are frightening.

This poignant debut perfectly captures the intense emotion, humor, and earnestness of young adulthood as Marty, age eleven to seventeen, navigates a series of life-changing firsts: first kiss, first enemy, first loss, and, ultimately, his first awareness that the world is not as simple a place as he had once imagined.

Includes a Reading Group Guide.

Genre:

-

"Wise and winning, THE MARTIN CHRONICLES is a sumptuous evocation of those adolescent afternoons when every moment was equally fraught and full of possibility. A charming, marvelous debut."Colson Whitehead, Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award-winning authorof The Underground Railroad

-

"A beautiful debut. THE MARTIN CHRONICLES transforms a series of adolescent snapshots into a raw, unforgettable mosaic."Stephen Chbosky, New York Times bestselling author of The Perks of Being a Wallflower

-

"John Fried's debut is a funny, tender, honest coming-of-age story, brimming with heart. THE MARTIN CHRONICLES is about first love and family and loss, but also, set on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in the '80s, it's a nostalgic look into the past and, in the end, a love story about that specific place and time."JuliannaBaggott, nationally bestselling author ofThe Seventh Book of Wonders

-

"Fried's lighthearted humor shines through...offers playful moments and an evocative atmosphere."Publishers Weekly

-

"Fried infuses every page with warmth and wonder."Booklist