By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

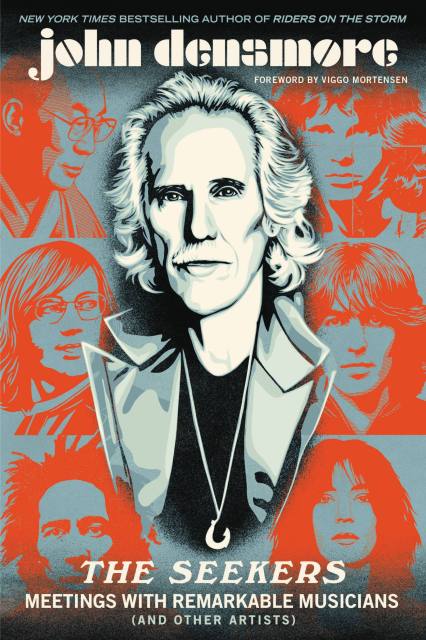

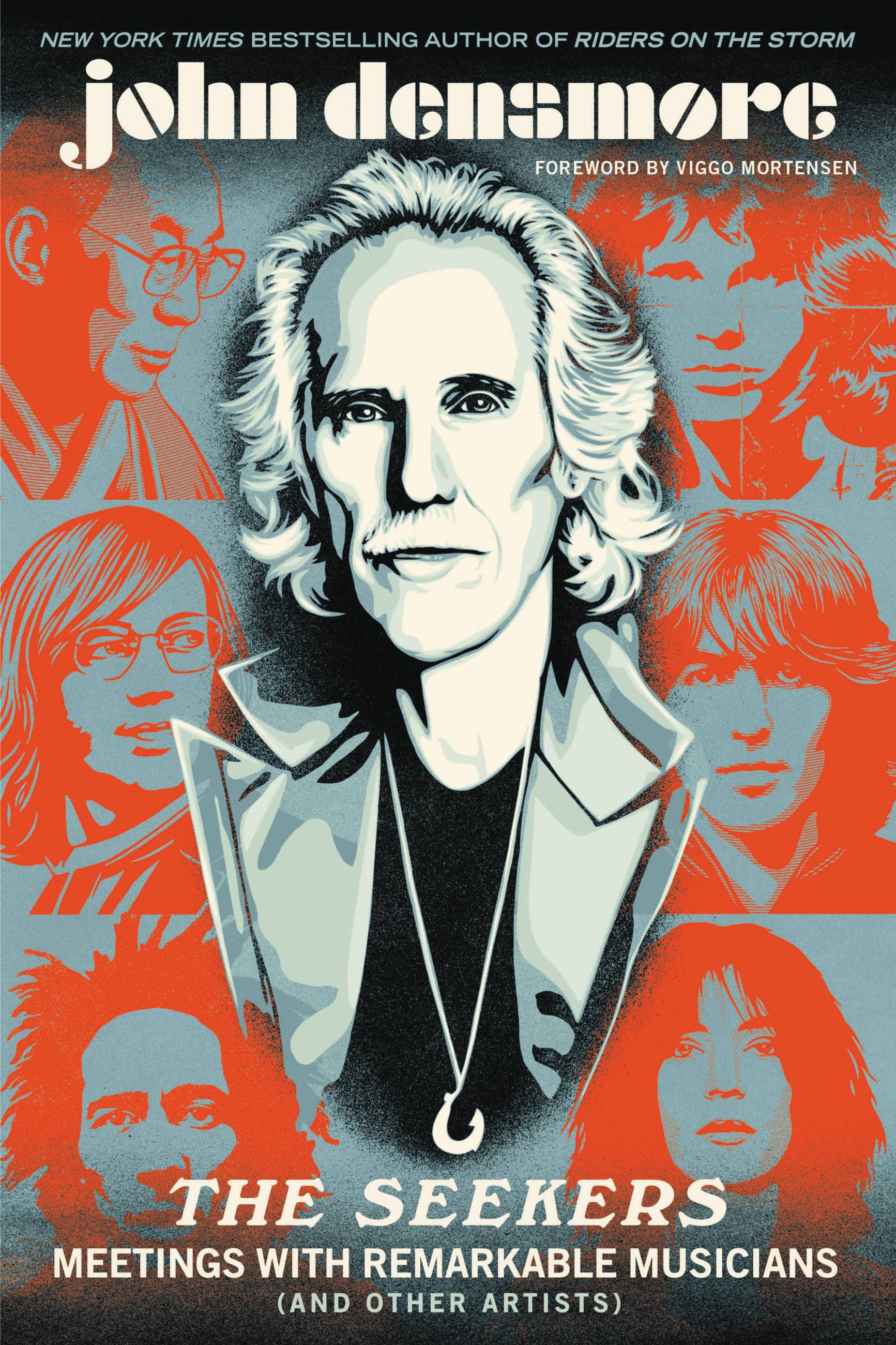

The Seekers

Meetings With Remarkable Musicians (and Other Artists)

Contributors

Foreword by Viggo Mortensen

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 16, 2021

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306846243

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 16, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Whether it’s the curiosity that blossoms after we listen to our favorite band’s newest record, or the sheer admiration we feel after watching a knockout performance, many of us have experienced art so pure-so innovative-that we can’t help but wonder afterwards: “How did they do that?” And yet, few of us are in a position to be able to ask those memorable legends where their inspiration comes from and how they translated it into something fresh and new. Fortunately for us, this book is here to offer us a bridge.

In The Seekers, John Densmore—the iconic drummer of The Doors and author of the New York Times bestseller Riders onthe Storm—digs deep into his own process and draws upon his privileged access to his fellow artists and performers in order to explore the origins of creativity itself. Weaving together anecdotes from the author’s personal notebooks and experiences over the past fifty years, this book takes readers on a rich, thought-provoking journey into the soul of the artist. By understanding creativity’s roots, Densmore ultimately introduces us to the realm of everyday inspirations that imbue our lives with meaning.

Inspired by the classic spiritual memoir Meetings with Remarkable Men, this book is fueled by Densmore’s abundant collection of transformative experiences—both personal and professional—with everyone from Ravi Shankar to Patti Smith, Jim Morrison to Janis Joplin, Bob Marley to Gustavo Dudamel, Lou Reed to Van Morrison, Jerry Lee Lewis to his own dear, late Doors bandmate Ray Manzarek. Ultimately, the result is not only a look into the hearts and minds of some of the most important artists of the past century—but a way for readers to identify and ignite their own creative spark, and light their own fire.

-

A Best Classic Bands’ “Best Music Book of the Year”

-

"John Densmore wrote this book about great artists he's known in the same fashion that he plays drums and lives his life. He understands and demonstrates the value of both silence and sound, space and statement. All the while, he brings us backstage to the parties and personalities that have inspired greatness and been cautionary tales of excess. He proves that it's never too late to grow and these are teachable moments from the life of a master."John Doe of X, and co-author of Under the Big Black Sun and More Fun in the New World

-

"I really enjoyed getting John's unique and insightful view of such an eclectic group of inspiring people."Bonnie Raitt, musician and activist

-

"John Densmore has the heart of a seeker. Always aiming, not for the sparrow, but for the eye of the sparrow in his search for meaning. His compass took him straight to the core of the moment and of the people he was drawn to by his uncanny ability to divine wisdom throughout his fairly frenzied life. It is reaffirming and gratifying to those of us who shared some of the same friends to revisit those unique and original souls."Olivia Harrison, author of George Harrison: Living in the Material World

-

“John Densmore is a true seeker, a force of good in the universe.”Jack Black, actor and musician

-

"John Densmore is a beautiful human being and a gift to us all. His lessons are profound and his eloquent words and voice touch us deeply."Ron Kovic, Vietnam Veteran and author of Born on the Fourth of July

-

“A joyful history lesson for music geeks.”SPIN

-

“[It's] fascinating it is to read this veteran musician's thoughts... these reflections should strike a resonant chord in any aficionado of the arts.”All About That Jazz

-

"A special kind of book... [this] easy-read is nothing short of magnificent."LA YOGA

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use