By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

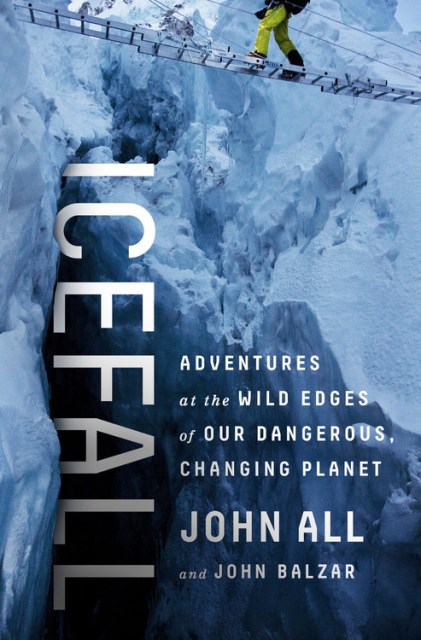

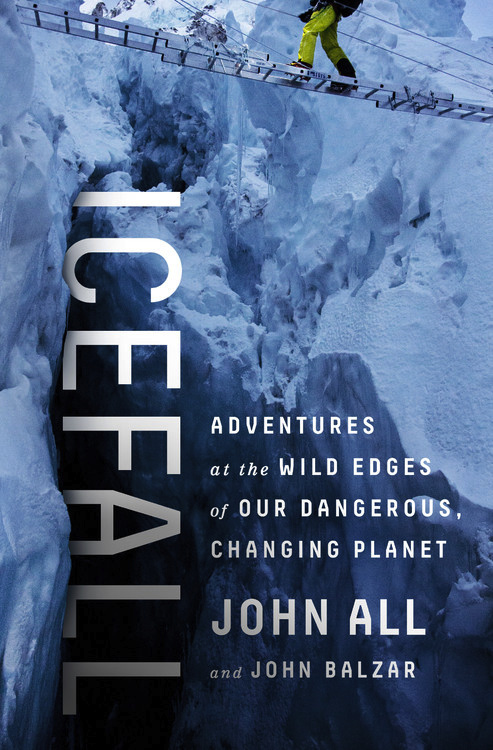

Icefall

Adventures at the Wild Edges of Our Dangerous, Changing Planet

Contributors

By John All

By John Balzar

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 14, 2017

- Page Count

- 248 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610396936

Price

$26.99Price

$34.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $26.99 $34.99 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 14, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In May 2014, the mountaineer and scientist John All plunged into a crevasse in the Himalayas, a fall that all but killed him. He recorded a series of dramatic videos as he struggled to climb seven stories back up to the surface with a severely dislocated shoulder, internal bleeding, a battered face covered in blood, and fifteen broken bones–including six cracked vertebrae. The videos became a viral sensation, an urgent and gripping dispatch from one of the least-known extremes of the planet.

Yet this climb for his life is only the latest of John All’s adventures in some of Earth’s most hostile climates. He has also been chased by a wild hyena, scaled Everest, and narrowly missed being hit by an avalanche, all in pursuit of his true calling: the study of how we can master the challenge of our world’s changing climate. Icefall is a thrilling adventure story and a report from the extremes of the planet, taking you to collapsing Andean glaciers, hidden jungles in Honduras, and the highest points on Earth. In this gripping account, our changing climate is not a matter of politics; it’s a matter of life and death and the human will to survive and thrive in the face of it.

-

"[John All is] a badass for science." -Adam Frank, NPR

-

"John All treads the delicate knife-edge between adventure and climate science in this gripping account of his work in some of the world's most dangerous and remote places. He makes a passionate and powerful case for human adaptation and resilience in the face of climate change. His optimism, from someone who has been there and done that, comes across loud and clear. In this book, climate change is not just politics-it's avalanches and huge snakes and getting lost in the desert. This book will make you see it in a new light."--Brian Fagan, distinguished emeritus professor of anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of The Great Warming

-

"[John All] is one part climate scientist and two parts extreme mountaineer, with insights into what it's like to work at the exciting-and sometimes dangerous-intersection between the pursuit of knowledge and the hunt for adventure." --Nate Blakeslee, author of Tulia: Race, Cocaine, and Corruption in a Small Texas Town

-

"Sure, some science happens in labs, with devices and machines. But data is in the world, where scientists interact with it, where they dig it out. Humanity, if it is looking to survive the next century in anything approaching its current state, needs more data to survive, especially data from places that are themselves rare: deserts, glaciers, mountains, still-impenetrable forests. It's giving nothing away to say that somehow John All, a mountain-climbing data forager extraordinaire, survives, despite all odds. Which offers humanity some hope, stuck as it is in a dark, life-on-earth-threatening place." --Robert Sullivan, author of The Meadowlands and My American Revolution

-

"John All's passion for adventure is matched only by his sharp insight and deep knowledge of environmental science. This important book tells the story of one man's crusade-through jungles, over mountains, and deep into the ice-to bring about change that could save millions of lives." --Carlos Buhler, winner of the American Alpine Club's Underhill Award for mountaineering

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use