By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

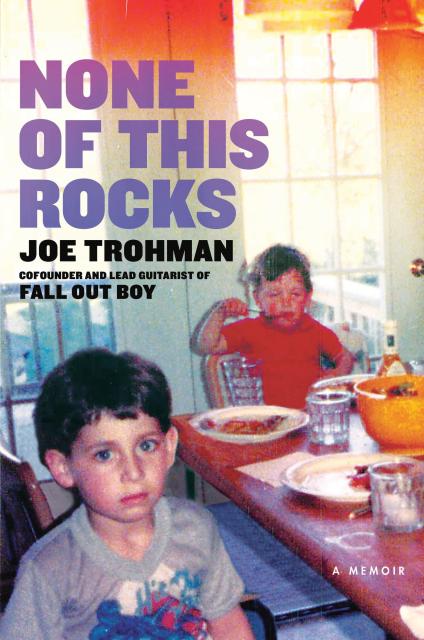

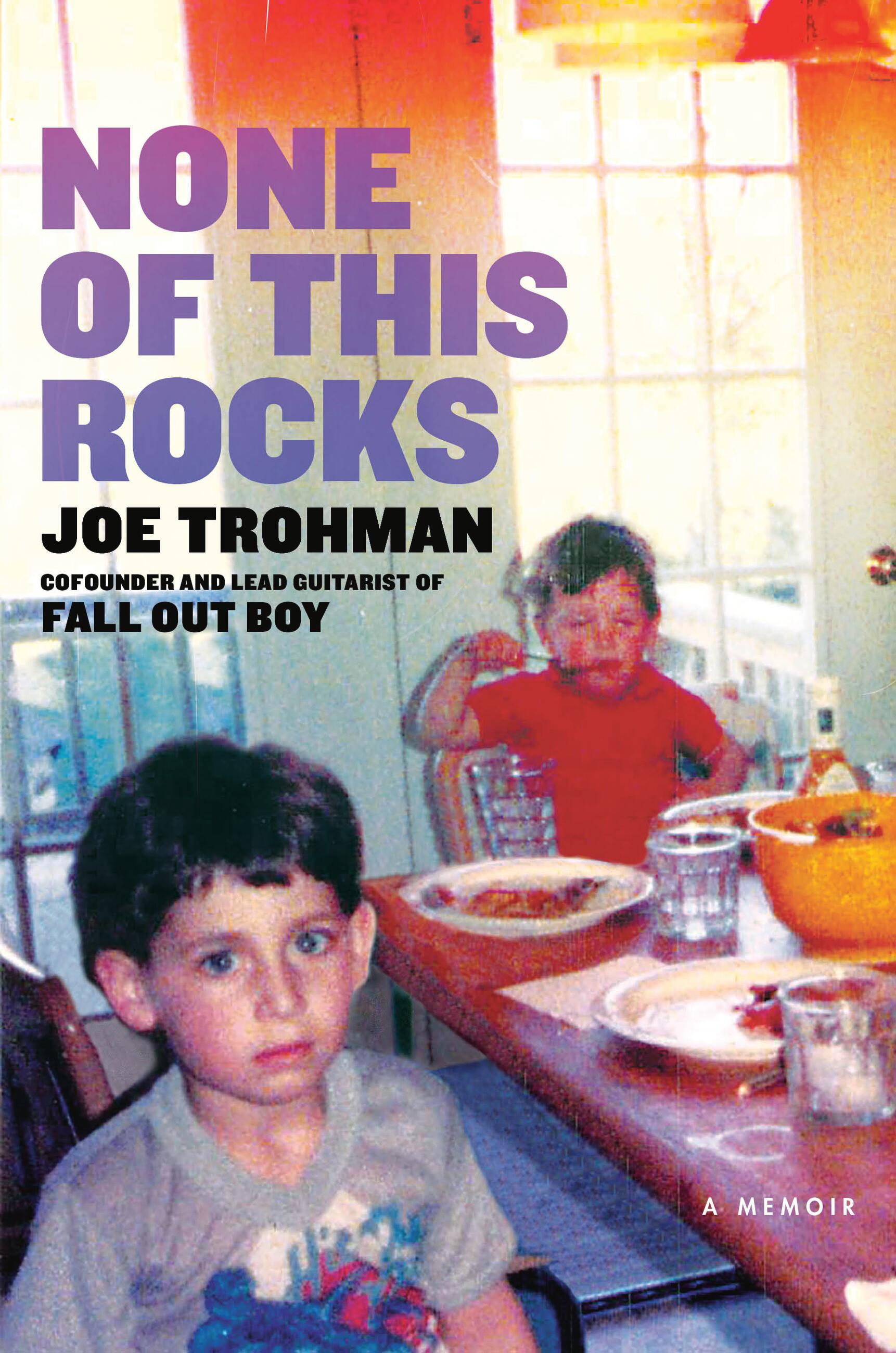

None of This Rocks

A Memoir

Contributors

By Joe Trohman

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 13, 2022

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306847332

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 13, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Lead guitarist and cofounder of Fall Out Boy shares personal stories from his youth and his experiences of modern rock and roll stardom in this memoir filled with wit and wisdom.

Trohman cofounded Fall Out Boy with Pete Wentz in the early aughts, and he’s been the sticky element of the metaphorical glue-like substance holding the band together ever since, over the course of a couple decades that have included massive success, occasional backlashes, and one infamous four-year hiatus. Trohman was, and remains, the emotive communicator of the group: the one who made sure they practiced, who copied and distributed the flyers, and who took the wheel throughout many of the early tours. As soon as he was old enough to drive, that is—because he was all of 15 years old when they started out. That’s part of the story Trohman tells in this memoir, which provides an indispensable inside perspective on the history of Fall Out Boy for their legions of fans. But Trohman has a great deal more to convey, thanks to his storytelling chops, his unmistakable voice, and his unmitigated sense of humor in the face of the tragic and the absurd.None of This Rocks chronicles a turbulent life that has informed Trohman’s music and his worldview. His mother suffered from mental illness and multiple brain tumors that eventually killed her. His father struggled with that tragedy, but was ultimately a supportive force in Trohman’s life who fostered his thirst for knowledge. Trohman faced antisemitism in small-town Ohio, and he witnessed all levels of misogyny, racism, and violence amid the straight edge hardcore punk scene in Chicago. Then came Fall Out Boy. From the guitarist’s very first glimpses of their popular ascension, to working with his heroes like Anthrax’s Scott Ian, to writing for television with comedian Brian Posehn, Trohman takes readers backstage, into the studio, and onto his couch. He shares his struggles with depression and substance abuse in a brutally honest and personal tone that readers will appreciate. Not much of this rocks, perhaps, but it all adds up to a fascinating music memoir unlike any you’ve ever read.

-

One of Buzzfeed’s 35 New Books You Won’t Be Able To Put Down

-

“A very different kind of rock memoir from most, offering a darkly funny, revealing, and relentlessly neurotic look at his own story and his band’s rise.”Rolling Stone

-

“With sharp wit and thoughtful examination, Trohman draws from his unique experience as he pulls back the curtain on his personal life. And while he delivers details on the formation and rise of Fall Out Boy, he also gets candid about his own history…. None of it's vague or sugar-coated. Instead, Trohman’s candor allows us to authentically glimpse into the highs and lows of his life growing up as a loner kid who loved music…. The book is fantastic.”Buzzfeed News

-

“[Joe Trohman’s] writing is infused with a sense of reflective wisdom that can only be fully realized through life experience and significant amounts of inner work, both of which serve as tentpoles to his narrative…. Despite some serious subject matter, the book is also so funny and completely in [his] own voice...“[A] can’t-put-down music memoir…[one of] the best memoirs this year…. Trohman’s distinct writing voice leans toward stream of consciousness, with vivid, absurdist commentary that trails off – almost like JD’s daydreams in Scrubs…. The memoir sheds light on how Trohman uses self-deprecating humor to shield him from anxiety, and that makes it all the more relatable….As an older and wiser human who has settled on healthier coping mechanisms, and created a family with a wife and two daughters he adores, Trohman has achieved a genuine wholesomeness through his growth (even as he continues making butthole jokes at our expense).”SPIN

-

“[A] rockin’ new memoir….really honest and open and very truthful….This is a conversation…felt like I was sitting with [Joe] and he was telling me a story…this is balls to the wall, no holds barred, good, bad, ugly, hilarious, heart-felt, everything in between, and we’re gonna take this ride together.”“Rock N Roll Grad School” podcast

-

“The charming ramble of None of This Rocks,a new memoir by Fall Out Boy co-founder Joe Trohman, [is] as blunt and dyspeptic a portrait of Chicago’s millennial punk scene (and growing up on the North Shore, and just being in a band) as I’ve come across in a while.”Chicago Tribune

-

“Trohman’s first book feels less like a traditional memoir and more like a surprising confessional from the guy sitting next to you on a cross-country flight. Even at 37, the author already has a fascinating life story. When he was 15, he went on his first punk-rock tour, following a few years of therapy prompted by his struggles with antisemitism in his elementary school and his tumultuous relationship with his mother, who was coping with brain cancer. Stunningly honest about his depression, low self-esteem, and drug addiction, Trohman also has a charming literary voice of his own, using self-deprecation and clever quips to keep things moving briskly.”Kirkus Reviews

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use