By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

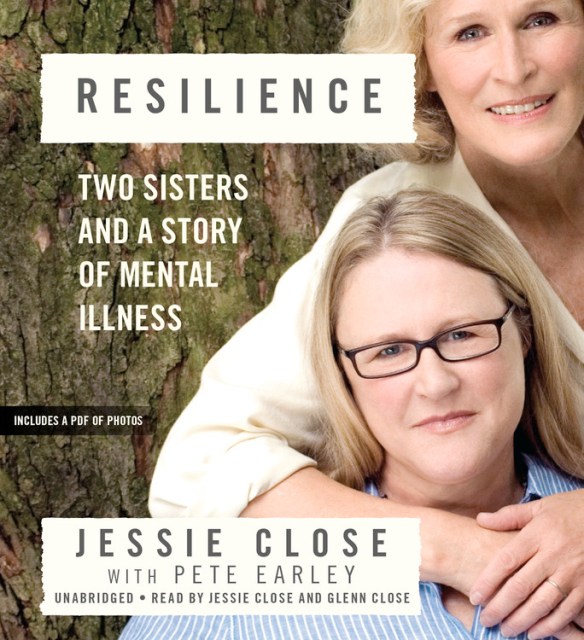

Resilience

Two Sisters and a Story of Mental Illness

Contributors

By Jessie Close

By Pete Earley

Read by Jessie Close

Read by Glenn Close

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 13, 2015

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478924531

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Hardcover (Large Print) $44.00 $55.00 CAD

- Hardcover $39.00 $49.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 13, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Jessie’s emerging mental illness led her into a life of addictions, five failed marriages, and to the brink of suicide. She fought to raise her children despite her ever worsening mental conditions and under the strain of damaged romantic relationships. Her sister Glenn and certain members of their family tried to be supportive throughout the ups and downs, and Glenn’s vignettes in Resilience provide an alternate perspective on Jessie’s life as it began to spiral out of control. Jessie was devastated to discover that mental illness was passed on to her son Calen, but getting him help at long last helped Jessie to heal as well. Eleven years later, Jessie is a productive member of society and a supportive daughter, mother, sister, and grandmother.

In Resilience, Jessie dives into the dark and dangerous shadows of mental illness without shying away from its horror and turmoil. With New York Times bestselling author and Pulitzer Prize finalist Pete Earley, she tells of finally discovering the treatment she needs and, with the encouragement of her sister and others, the emotional fortitude to bring herself back from the edge.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use