Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

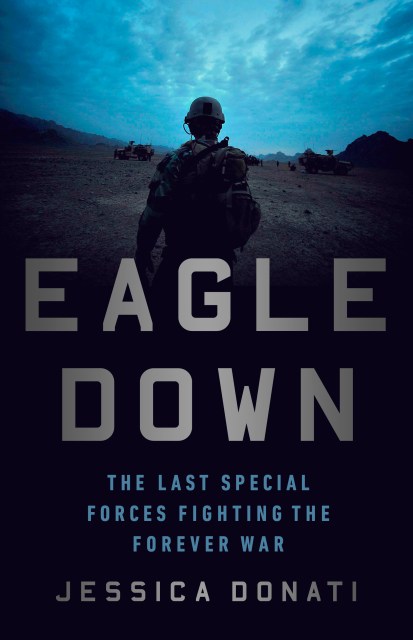

Eagle Down

The Last Special Forces Fighting the Forever War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 19, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541762572

Price

$16.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 19, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A Wall Street Journal national security reporter takes readers into the lives of frontline U.S. special operations troops fighting to keep the Taliban and Islamic State from overthrowing the U.S.-backed government in the final years of the war in Afghanistan.

A FINANCIAL TIMES BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR

“Powerful, important, and searing." —General David Petraeus, U.S. Army (ret.), former commander, U.S. Central Command, former CIA director

In 2015, the White House claimed triumphantly that “the longest war in American history” was over. But for some, it was just the beginning of a new war, fought by Special Operations Forces, with limited resources, little governmental oversight, and contradictory orders.

With big picture insight and on-the-ground grit, Jessica Donati shares the stories of the impossible choices these soldiers must make. After the fall of a major city to the Taliban that year, Hutch, a battle-worn Green Beret on his fifth combat tour was ordered on a secret mission to recapture it and inadvertently called in an airstrike on a Doctors Without Borders hospital, killing dozens. Caleb stepped on a bomb during a mission in notorious Sangin. Andy was trapped with his team during a raid with a crashed Black Hawk and no air support.

Through successive policy directives under the Obama and Trump administrations, America came to rely almost entirely on US Special Forces, and without a long-term plan, failed to stabilize Afghanistan, undermining US interests both at home and abroad.

Eagle Down is a riveting account of the heroism, sacrifice, and tragedy experienced by those that fought America’s longest war.

Genre:

-

“Afghanistan is one of the most dangerous countries in the world, and U.S. Special Forces are one of the most secretive groups in America's military. That Jessica Donati managed to crack both and write a book that is both brutally honest and deeply compassionate about this elite group is a journalistic triumph. It is beautifully written, impossible to put down and deeply terrifying for anyone who has worked in that country. She's one of those writers who makes me deeply proud of my profession.”Sebastian Junger, New York Times best-selling author

-

“Donati’s book has a particular resonance. Her closely reported story of US special forces operations in Afghanistan captures much of the chaos and tragedy of the conflict and the human costs involved.”Financial Times, Best Books of 2021: Politics

-

"Donati's on-the-ground account-and it's clear that she put herself in constant danger to tell the soldiers' stories even as American officials dithered about how to deploy those troops-is sometimes as hallucinatory as Dispatches and as taut and well written as Mark Bowden's now-classic book...Exemplary journalism and a powerful argument for not putting soldiers in harm's way unless we're sure we know why."Kirkus Reviews, starred review

-

“Skillfully interweaving big-picture policy analysis with frontline reporting, Donati shines a stark light on this shadowy conflict. The result is a distressing yet vital update on America’s longest war.”Publishers Weekly

-

“The book hits its mark in its sympathetic portrayal of the boots on the ground, in particular the Special Forces and Green Berets of Operational Detachment Alpha. Their frustrations at the human costs, from deaths to homesickness to mission futility, will resonate with readers.”Booklist

-

“Eagle Down is a gripping story of a war most Americans had thought was over or had wrongly forgotten about entirely.”The Diplomatic Courier

-

"The book’s interweaving narrative style paired with Donati’s meticulous reporting makes Eagle Down as engaging and touching as it is insightful."Stars and Stripes

-

“Highly enlightening.. [an] incisive and brutally frank account.”The New York Journal of Books

-

“[Donati’s] vivid, uncompromising reporting presents U.S. politicians and senior military commanders as disconnected from the reality of the war as they flounder in search of a satisfactory way out of it.”Foreign Affairs

-

“Ultimately this book is about tragedy, the tragedy of loss, the tragedy of bad decisions, and the tragedy of futility. But it is also a book of survival, perseverance and personal strength. More importantly it’s a book that doesn’t pull any punches. If you are looking for a story that depicts Green Berets as comic book super heroes then you came to the wrong place. If, however, you are looking for an unvarnished depiction of the successes, failures, and losses of men who have put everything on the line for the things they believe in then Eagle Down is for you.”Small Wars Journal

-

“A memorable portrait of Americans fighting in Afghanistan over the last six years. Donati does an especially good job at portraying the combat in Kunduz in October 2015…an important story about limited warfare.”The New York Times Book Review

-

“Jessica Donati deserves a Pulitzer Prize for this extraordinary book about America’s continued behind the scenes fighting in Afghanistan’s “Forever War.”The San Francisco Book Review

-

“Jessica Donati’s excellent but tragic book… Eagle Down will rank among the most impactful books I have read about military affairs. A terrific book, written by an engaging author.”BookMarc

-

“Donati, a veteran Wall Street Journal correspondent, writes a gripping and gut-wrenching account of the battle-weary special forces on the front lines of the war in Afghanistan’s final stages. I couldn’t put it down.Foreign Policy