By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

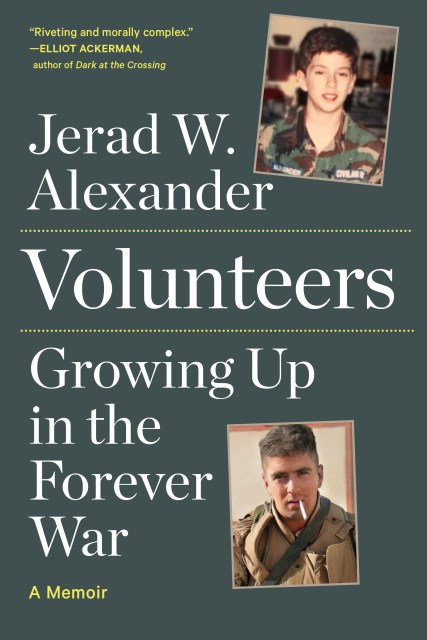

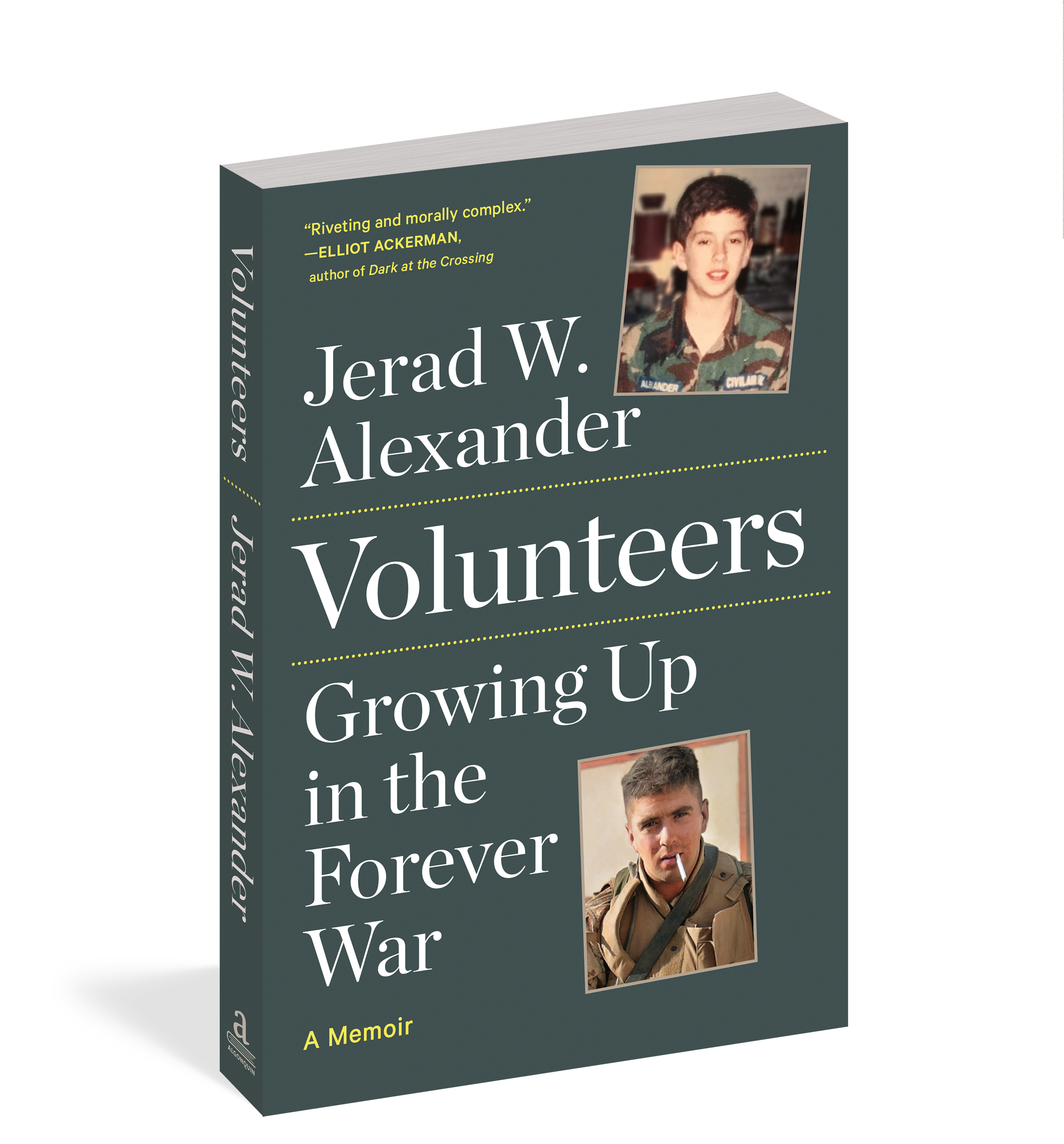

Volunteers

Growing Up in the Forever War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 8, 2022

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643753256

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.95

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 8, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As a child, Jerad Alexander lay in bed listening to the fighter jets take off outside his window and was desperate to be airborne. As a teenager at an American base in Japan, he immersed himself in war games, war movies, and pulpy novels about Vietnam. Obsessed with all things military, he grew up playing with real guns, joined the Civil Air Patrol for the uniform, and dreamed of enlisting and playing his part in the Great American War Story. Once in Iraq as a U.S. Marine, however, he came to realize he was fighting a lost cause, enmeshed in the ongoing War on Terror that was really just a fruitless display of American might. The myths of war, the stories of violence and masculinity and heroism, the legacy of his family—everything Alexander had planned his life around—was a mirage.

Alternating scenes from childhood with skirmishes in the Iraqi desert, this original, searing, and propulsive memoir introduces a powerful new voice in the literature of war. Jerad W. Alexander—not some elite warrior, but a simple volunteer—delivers a passionate and timely reckoning with the troubled and cyclical truths of the American war machine.

-

“Riveting and morally complex, Volunteers is not only an insider’s account of war. It takes you inside the increasingly closed culture that creates our warriors. In the case of Jerad W. Alexander, that culture has also created a writer of remarkable talent.”Andrew Bacevich, author of After the Apocalypse: America's Role in a World Transformed

B>Elliot Ackerman, author of the National Book Award finalist Dark at the Crossing

“A beautiful and powerfully affecting portrait of a boyhood in a military family, in which contrasting and ever more complex views of America, of war, and of what it means to be a soldier lead to the decision to join the military and serve in Iraq. In that way, it’s also a portrait of the stories we tell ourselves, and how those stories fare when our children grow up and try to live them.”

B>Phil Klay, author of Redeployment (winner of the National Book Award) and Missionaries

“With this work, Jerad W. Alexander has staked his claim as one of the most necessary voices while contributing to a necessary and overdue examination of our military culture and what it means to be an American. An absolute triumph.”

B>Jared Yates Sexton, author of American Rule: How a Nation Conquered the World but Failed Its People

“Alexander offers a well-attuned perspective of the military world and how its expansive influence not only motivates, but also arouses a justification for war itself . . . Alexander’s insights into the myth-building ethos of the military . . . are well articulated, and he ably explores ideals of masculinity, heroism, and camaraderie within the military establishment . . . Alexander vividly captures the foreboding atmosphere of a country under siege and recounts the disturbing incidents he witnessed during his seven-month deployment . . . An absorbing memoir reflecting the realities of serving in the modern-day military.”

B>Kirkus Reviews

“What sets apart Volunteers from other literary treatments of modern conflict is that it understands war is not a destination but a state of being. 'The war is everywhere,' Jerad W. Alexander writes in this beautiful, dark chronicle of an American life and lineage shaped by empire. This testament to moral and physical courage deserves all the accolades about to come its way and more. Volunteers is exceptional.”

B>Matt Gallagher, author of Youngblood and Empire City

“A reckoning of American identity, masculinity, and exceptionalism that dissects the U.S. military ethos, while capturing the popular culture that shaped a generation of service members. An eloquent and compelling memoir, written in the language of candor, humor, and grim realism.”

B>Dewaine Farria, author of Revolutions of All Colors

“Volunteers is a compelling twofer. In it, Jerad Alexander recounts his coming of age in an environment that glamorized war and his own subsequent encounter with the singularly unglamorous reality of combat. Vivid, intimate, and moving, Volunteers belongs on the very top shelf of ‘forever war’ memoirs.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use