Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

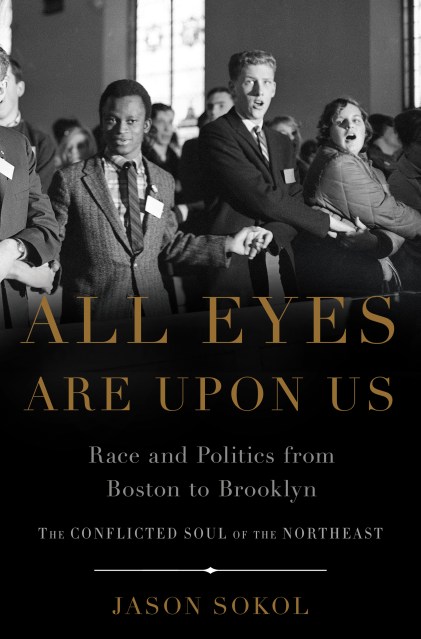

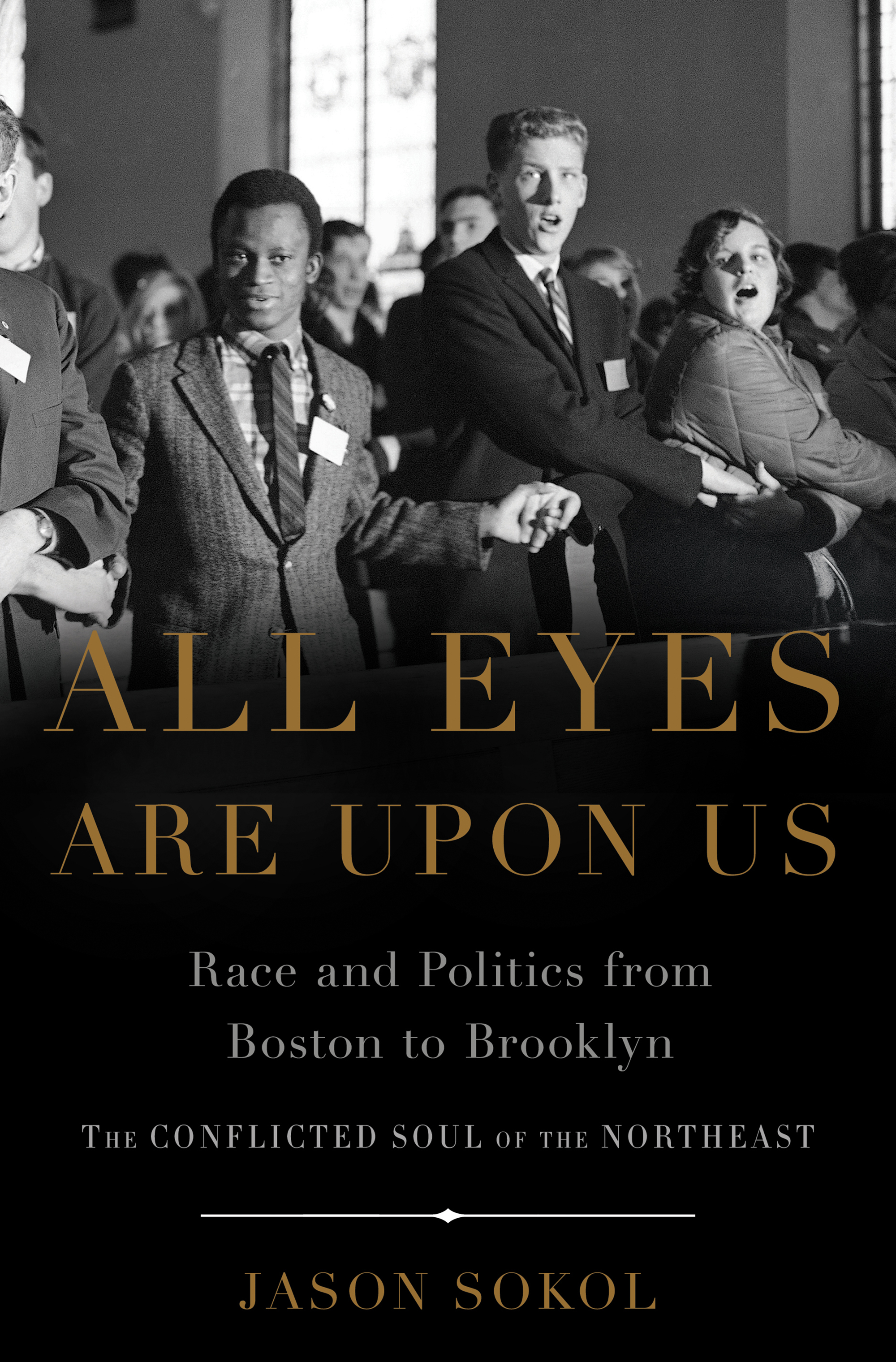

All Eyes are Upon Us

Race and Politics from Boston to Brooklyn

Contributors

By Jason Sokol

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 2, 2014

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465056712

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $19.99 $25.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 2, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

White fans from across Brooklyn — Irish, Jewish, and Italian — came out to support Jackie Robinson when he broke baseball’s color barrier with the Dodgers in 1947, even as the city’s blacks were shunted into segregated neighborhoods. The African-American politician Ed Brooke won a senate seat in Massachusetts in 1966, when the state was 97% white, yet his political career was undone by the resistance to busing in Boston. Across the Northeast over the last half-century, blacks have encountered housing and employment discrimination as well as racial violence. But the gap between the northern ideal and the region’s segregated reality left small but meaningful room for racial progress. Forced to reckon with the disparity between their racial practices and their racial preaching, blacks and whites forged interracial coalitions and demanded that the region live up to its promise of equal opportunity.

A revelatory account of the tumultuous modern history of race and politics in the Northeast, All Eyes Are Upon Us presents the Northeast as a microcosm of America as a whole: outwardly democratic, inwardly conflicted, but always striving to live up to its highest ideals.