By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

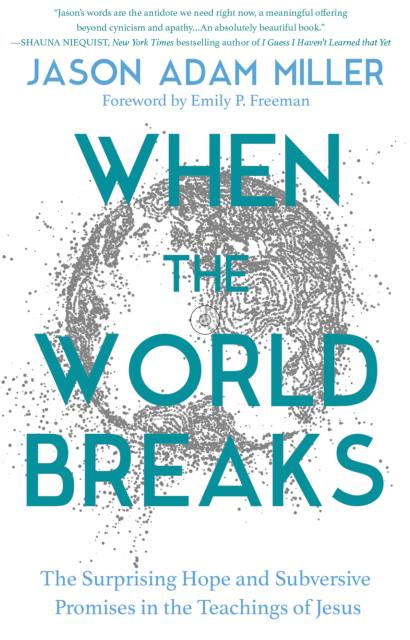

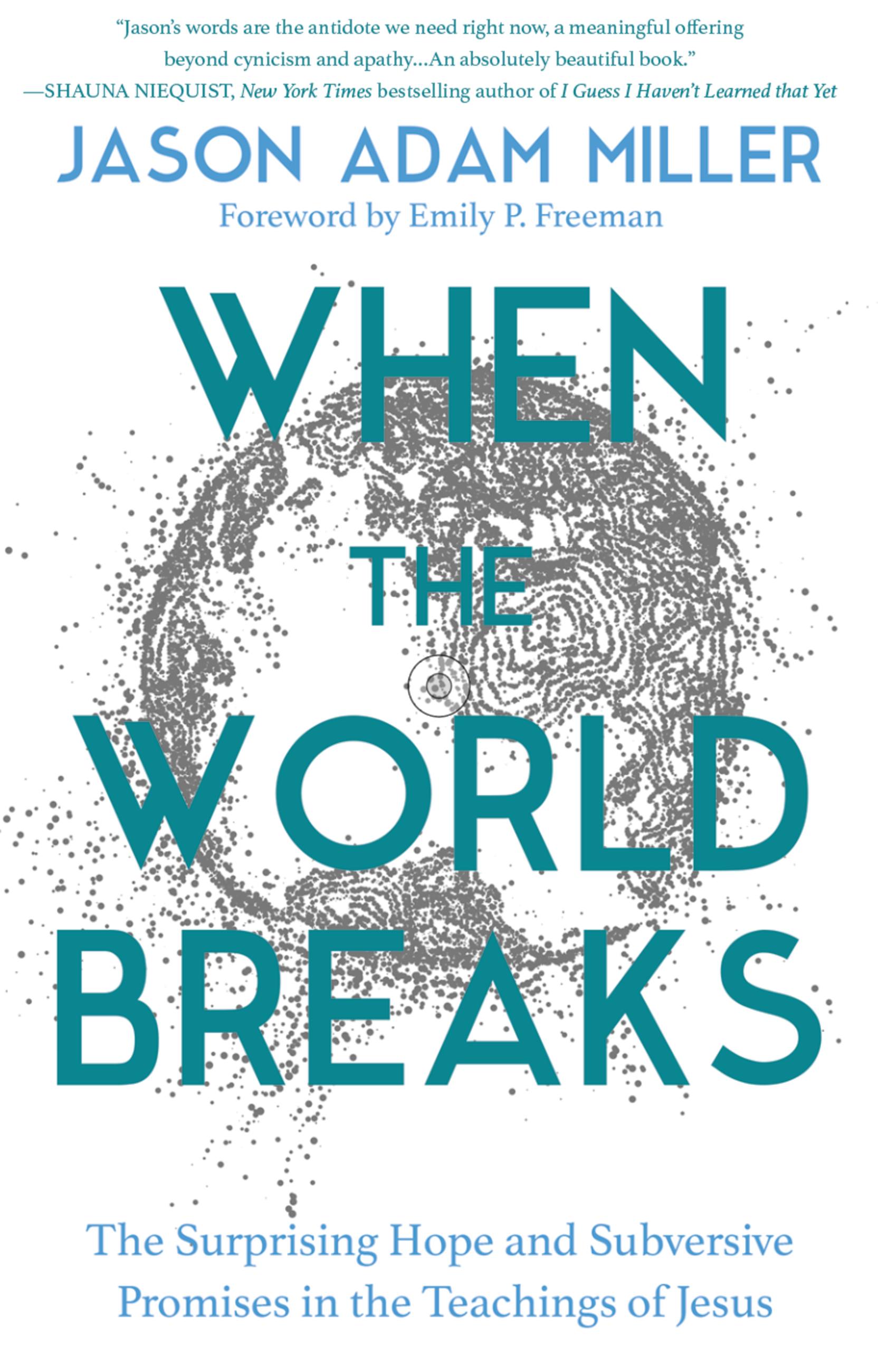

When the World Breaks

The Surprising Hope and Subversive Promises in the Teachings of Jesus

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 1, 2023

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- FaithWords

- ISBN-13

- 9781546003502

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 1, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this groundbreaking book, Pastor Jason Adam Miller re-examines the Beatitudes—eight paradoxes found in Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount—and points to a whole new way to find hope in the midst of suffering.

If the past few years have taught us anything, it’s that the world is broken. The world we thought we knew vanished, and so many of us are now struggling to make sense of a world that’s not what we thought it was.This book is about what happens when the fundamental picture we had relied on – our sense of how everything holds together – falls apart. For some, this moment comes when a global pandemic upends our security. For others, it’s a partner leaving, or a terrible diagnosis, or the death of a loved one. Many of us have felt our worlds breaking when long-held beliefs about God or faith slipped through our hands. Whether the details are global or personal, the experience is the same: you discover that the framing reality you were living in has fractured.

But here’s the good news: The world has been breaking for as long as we can remember. We’ve been here before, which means we can turn to ancient, perennial wisdom to help us sort through these urgent problems. In When the World Breaks, Jason Adam Miller explores the possibilities for hope hidden in the paradoxes Jesus spoke when he taught the eight blessings – often called the Beatitudes – recorded in the beginning of Matthew chapter 5. These strange blessings name our experiences of suffering and are built on a particular kind of hope. This book is a meditation on those teachings as a transformative way forward when we suffer.

Lyrically written, theologically rich, and supremely accessible, When the World Breaks reveals an unexpected way to look at these familiar verses, giving readers hope that God is with them in their suffering, and helping them become the kind of people who can put things back together.

-

"Jason’s words are the antidote we need right now, a meaningful offering beyond cynicism & apathy… An absolutely beautiful book.”Shauna Niequist, New York Times Bestselling author of I Guess I Haven’t Learned That Yet

-

"I deeply loved this book. Not only is Jason Miller one of my favorite pastors I’ve ever known, now I have to add him to my list of favorite authors. An important book for our current cultural conversation."Scott Erickson, author of Honest Advent and Say Yes

-

"For a long time, words of Jesus have seemed to be held hostage by people determined to make them complicated and confusing. What this book does is make those words simple and beautiful and hopeful again. This book is absolutely necessary for anyone who is tired of an overly complicated Jesus and ready for a little hope.”Brit Barron, author of Worth It

-

"A powerful book about the hardest things we face and the hope we can find in life's darkest moments. Its sober assessment of the darkness and fearless mission to chart a path toward the light will, at once, rivet and comfort readers. I highly recommend it.”Jonathan Merritt, author of Learning to Speak God From Scratch and contributor for The Atlantic

-

"Jason Miller is not only a friend, but serves me as a helpful guide and needed voice in navigating America's often tense and temperamental church and culture landscape. HIs heart for the suffering, disillusioned and those who are rightly triggered by traumatic experiences and exposures to a toxic, unhelpful, and exclusive version of Christianity, runs through every sentence of When the World Breaks. Even more than that, this book is brimming with Jason's full-throated, sensitive, approachable, and enticing love for the teachings of Jesus — a Jesus who is present in our suffering.”Sean Palmer, author of Speaking By the Numbers and Unarmed Empire

-

"When we exist for too long in broken spaces, it’s easy to forget our deep desire for wholeness. When the World Breaks is an invitation to remember. Through vulnerable storytelling, robust Biblical wisdom, and a generous eye toward hope, cynicism fades and possibility pushes through the weary soul… This book changed me.”Shannan Martin, author of Start with Hello and The Ministry of Ordinary Places

-

"Jason Miller doesn't offer false hope that life will always be the way you want, but instead he offers a dependable hope that all will one day need. The hope that something happens on the other side of everything falling apart. With the heart of a poet and the mind of a scholar, Jason has given the world a much needed gift in writing When the World Breaks."Luke Norsworthy, pastor and author of Befriending Your Monsters

-

"When your world cracks, fractures, breaks and you feel at the end of your rope searching for any semblance of hope; trusted voices like Jason Miller are a rare gift for how they can thoughtfully guide you through the profound mystery that is your life and the ancient beatitudes. The writing and ideas are absolutely stunning and will help you discover how to kindly move forward. I didn’t know how much my heart needed this book!”Steve Carter, author of The Thing Beneath the Thing

-

"Jason has written a must-read for anyone who feels like their world is breaking—which is all of us at one point or another. If you long for a humble, nuanced perspective on suffering and hope, this book is for you. If you want to become the kind of person who helps put the world back together, there is no better person to learn from than Jason... who points us to Jesus in the most accessible and refreshing way.”Manda Carpenter, author of Soul Care to Save Your Life

-

"This is a beautiful book. It's a work which brings a defiant yet tender challenge to the loud societal voices of polarisation and indifference. Jason's words rhyme with the ancient wisdom of the first Christians and the way they chose to walk. This Jesus-way is most clearly seen in the Sermon on the Mount and more specifically in the Beatitudes. I have stood many times on the Mount of Beatitudes and reflected on these words. I have never heard these ancient Blessings more resonantly unpacked than in this book.Jonny Clark, public theology at The Corrymeela Community and podcaster at Guardians of the Flame

Jason Miller is a friend who has emptied his soul on to the lines of these pages. In doing so he unveils a beautiful Jesus-looking God. I live in Northern Ireland. We have become experts in binary thinking and in the separating of "them" from "us". Jason unpacks the beauty of Borderland spaces. Where Jason goes, unique beauty emerges. He doesn't live in a world of false equivalence, of keeping the peace by avoiding conflict. Rather this book is an embodiment of his life, which is about setting up a tent in the borderlands, a brave space for sacred stories, where oppositional forces can find common ground and a unique forest of biodiversity can be planted and enjoyed.”