By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

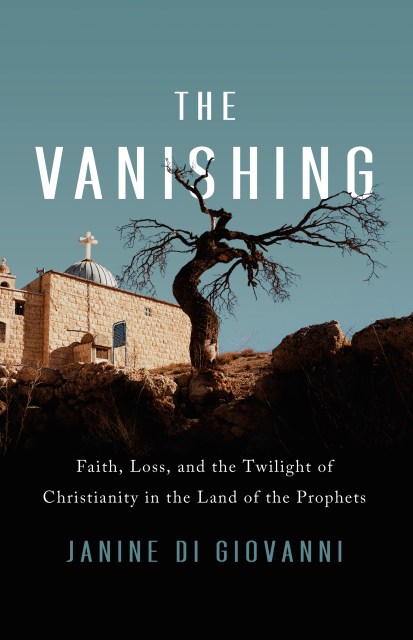

The Vanishing

Faith, Loss, and the Twilight of Christianity in the Land of the Prophets

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 5, 2021

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541756717

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 5, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Vanishing reveals the plight and possible extinction of Christian communities across Syria, Egypt, Iraq, and Palestine after 2,000 years in their historical homeland.

Some of the countries that first nurtured and characterized Christianity – along the North African Coast, on the Euphrates and across the Middle East and Arabia – are the ones in which it is likely to first go extinct. Christians are already vanishing. We are past the tipping point, now tilted toward the end of Christianity in its historical homeland. Christians have fled the lands where their prophets wandered, where Jesus Christ preached, where the great Doctors and hierarchs of the early church established the doctrinal norms that would last millennia.

From Syria to Egypt, the cities of northern Iraq to the Gaza Strip, ancient communities, the birthplaces of prophets and saints, are losing any living connection to the religion that once was such a characteristic feature of their social and cultural lives.

In The Vanishing, Janine di Giovanni has combined astonishing journalistic work to discover the last traces of small, hardy communities that have become wisely fearful of outsiders and where ancient rituals are quietly preserved amid 360 degree threats. Di Giovanni’s riveting personal stories and her conception of faith and hope are intertwined throughout the chapters. The book is a unique act of pre-archeology: the last chance to visit the living religion before all that will be left are the stones of the past.

Genre:

-

“The book illustrates the fine balance in which many of these communities now hang, examining how violence, economic instability, persecution, and emigration are leading to the dissolution of cultures forged both by land and by religion.”The New Yorker

-

“The individuals di Giovanni interviews provide a rich portrait of these threatened communities, and of the wider societies they inhabit.”Harper’s Magazine

-

“The Vanishing, a mosaic of oral histories, paints a picture of the religion almost lost but preserved through collective memory in the Promised Land where Jesus Christ once walked.”Vanity Fair

-

“In the hands of a skilled storyteller, this is a sad and moving account of a historic change.”Financial Times

-

“[W]ith beautiful evocations of the power of faith in trying times…it’s refreshing to hear from a correspondent who participated in, rather than merely observed, one of the most fundamental aspects of life in the Middle East: religious practice…di Giovanni does Middle Eastern Christians a service by highlighting their recent struggles.”The Wall Street Journal

-

“The Vanishing is neither a chronological record of Christian withdrawal nor a geopolitical analysis of religious trends. Instead, di Giovanni offers a kind of requiem for a disappearing religious culture, a tale rendered all the more heart-wrenching for having been written during some of the worst months of the COVID-19 crisis. The book skillfully manages to combine an overview of the rise and precipitous fall of Christianity in its ancient homelands, moving accounts from believers sticking it out there, and a deeply personal grieving over the withdrawal of the faith from its birthplace.”Christianity Today

-

“The Vanishing is unique because di Giovanni is not seeking a solution, and indeed knows there may not be one. As a war reporter for 30 years she knows the reality of man: There will always be another war, there will always be slaughter and destruction. She writes because this is the twilight of Middle Eastern Christianity, because just maybe we’ll remember their stories.”First Things

-

“With grace and deep reporting, Janine di Giovanni, an acclaimed author and war correspondent, has captured the often overlooked plight of the dwindling Christian communities of the Middle East—specifically in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Palestine. The Vanishing is a tender if deeply disturbing travelogue, filled with stories told by Christians about the ferocious politics and desperate economics that shattered their communities. She writes in an elegiac tone while marveling at the resiliency of the few who remain… The Vanishing is an unexpected gift, preserving the story of the last remnants of Christian communities rooted in the region of the faith’s birth.”Sojourners

-

“There could scarcely be a better person than Janine di Giovanni to write about the disappearing Christians of the Middle East. An award-winning war correspondent, she brings compassion, experience, and expertise to the subject.”Lara Marlowe, The Irish Times

-

“Di Giovanni's mesmeric narrative is an elegant balance of journalism and history that also includes semi-autobiographical reflections of the role faith plays in her own life. Seeking to illuminate those ‘worlds and communities of people who might, in one hundred years' time, no longer be on this earth,’ di Giovanni grants life forever on the page to those vanishing now… This is a rewarding, thoughtful and somber journey into the Middle East to find the last ‘holdouts’ of the Christian faith in Iraq, Syria, Gaza and Egypt.”Shelf Awareness

-

“[DiGiovanni] writes with poignant authenticity as she weaves her own deeply personal faith experiences with those of a parade of Middle Eastern citizens who populate the history she recounts of Iraq, Gaza, Syria, and Egypt, places foundational to early Christianity… Di Giovanni’s many interviews and own observations detail heartrending circumstances that have wreaked irreparable harm to families, towns, and countries. The words of one Syrian expat, ‘Our present is a failure, but our past is glorious,’ illustrate di Giovanni’s difficult, essential undertaking.”Booklist

-

“In this informative work of journalism and memoir, war reporter Di Giovanni (Ghosts of Daylight) recounts her travels through the Middle East with a focus on rapidly shrinking Christian minority groups…The propulsive account is marked by the author’s keen eye for detail and the stories of the people involved… perfect for anyone interested in the Middle East, or in how humans live through war.”Publishers Weekly

-

“In her latest poignant book, veteran war correspondent and Guggenheim fellow di Giovanni focuses on Christian communities struggling to survive in the region where the religion had its birth… The author presents a distinctly personal and subjective account full of empathy and humanity amid upheaval.”Kirkus

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use