By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

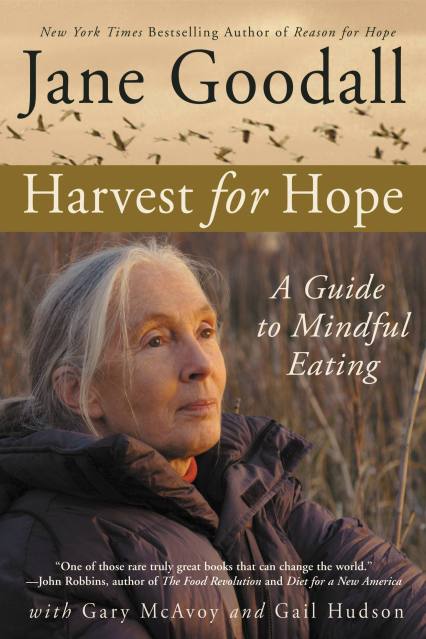

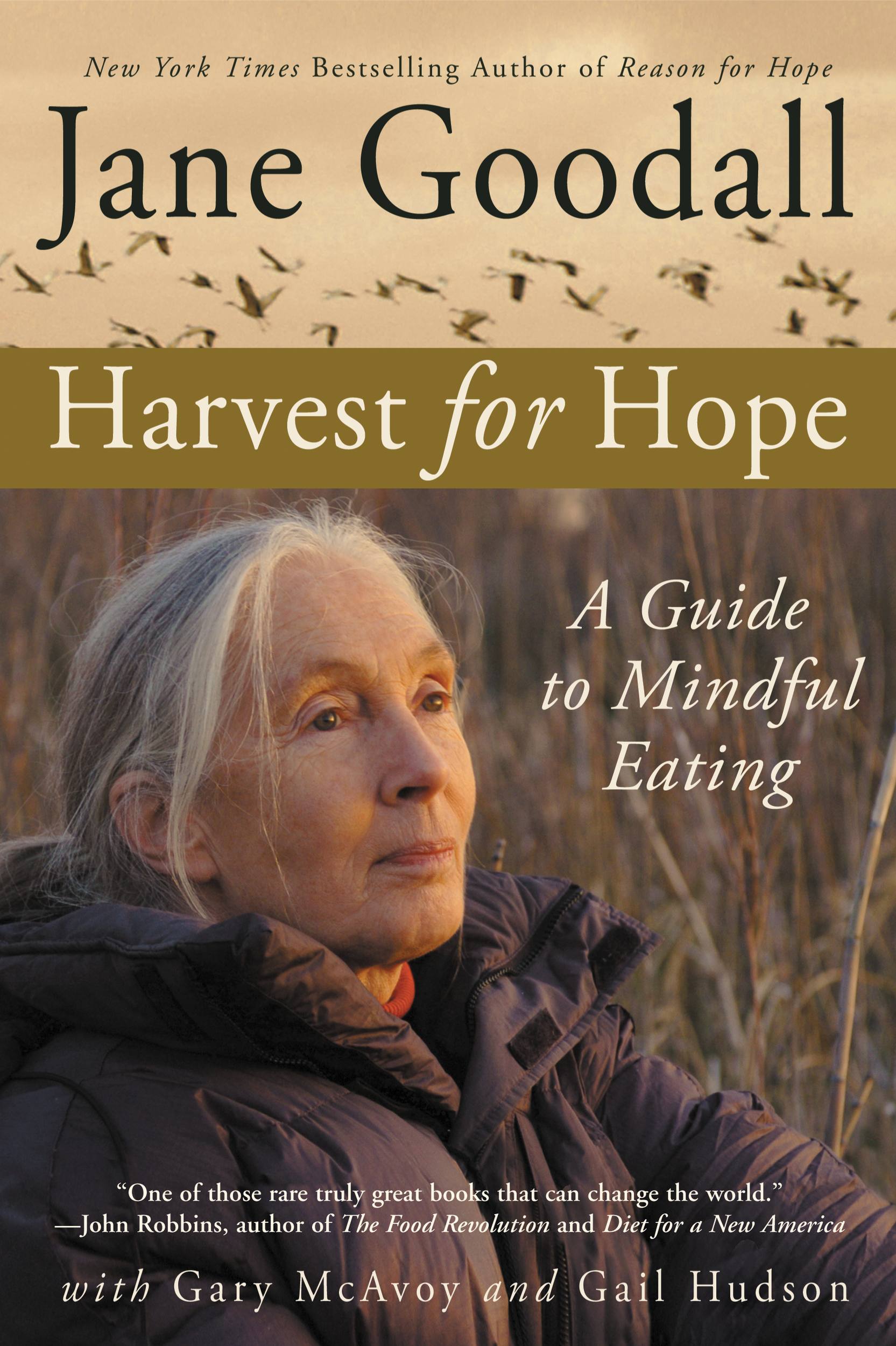

Harvest for Hope

A Guide to Mindful Eating

Contributors

By Jane Goodall

By Gary McAvoy

By Gail Hudson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 1, 2005

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780759514867

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Abridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 1, 2005. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

"One of those rare, truly great books that can change the world." —John Robbins, author of The Food Revolution

The renowned scientist who fundamentally changed the way we view primates and our relationship with the animal kingdom now turns her attention to an incredibly important and deeply personal issue—taking a stand for a more sustainable world.

In Harvest for Hope, Jane Goodall sounds a clarion call to Western society, urging us to take a hard look at the food we produce and consume—and showing us how easy it is to create positive change. Offering her hopeful, but stirring vision, Goodall argues that each individual can make a difference. She provides simple strategies each of us can employ to foster a sustainable society.

Brilliant, empowering, and irrepressibly optimistic, Harvest for Hope is a crucial book for our age. If we follow Goodall's sound advice, we just might save ourselves before it's too late.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use