By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

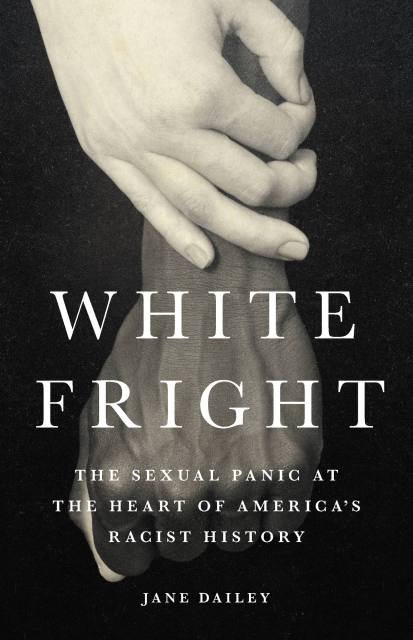

White Fright

The Sexual Panic at the Heart of America's Racist History

Contributors

By Jane Dailey

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 17, 2020

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541646544

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 17, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A major new history of the fight for racial equality in America, arguing that fear of black sexuality has undergirded white supremacy from the start.

In this urgent investigation, Dailey examines how white anxiety about interracial sex and marriage found expression in some of the most contentious episodes of American history since Reconstruction: in battles over lynching, in the policing of black troops’ behavior overseas during World War II, in the violent outbursts following the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, and in the tragic story of Emmett Till. The question was finally settled — as a legal matter — with the Court’s definitive 1967 decision in Loving v. Virginia, which declared interracial marriage a “fundamental freedom.” Placing sex at the center of our civil rights history, White Fright offers a bold new take on one of the most confounding threads running through American history.

-

"This indispensable narrative powerfully illuminates how anxieties about 'miscegenation' and interracial marriage shaped and sustained white supremacy for four centuries. Every American should read this book."Drew Gilpin Faust, author of This Republic of Suffering

-

"In White Fright historian Jane Dailey skillfully untangles the purposefully snarled concepts of sex, marriage, and politics at the foundation of the White supremacist American political economy that followed Reconstruction. More than a century and a half later, such gut-level concepts underlie our current politics, making White Fright essential reading right now. As Dailey shows, the history of anti-Blackness is White history."Nell Irvin Painter, author of Southern History Across the Color Line

-

"To understand the true virulence of white supremacy in America, and to grasp just how hard won the fights against it have been, one must reckon with the extent to which racist laws and actions have always, in fact, been fueled by white obsessions about sex. Jane Dailey's latest, a most powerful recovery of this insidious history, must be read by all."Heather Ann Thompson, Pulitzer Prize-Winning author of Blood in the Water

-

"Jane Dailey's peerless contribution is the revelation of how African Americans came to rebut not only the arch segregationists of the Deep South, but also the white moderates who dared to prescribe what Blacks "ought to want"-even after the Nazis copied the laws that such well-to-do whites helped keep in place. A must-read to understand how the right to choose whom to love and marry lost its centuries-old exclusivity."Nancy MacLean, author of Democracy in Chains