By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

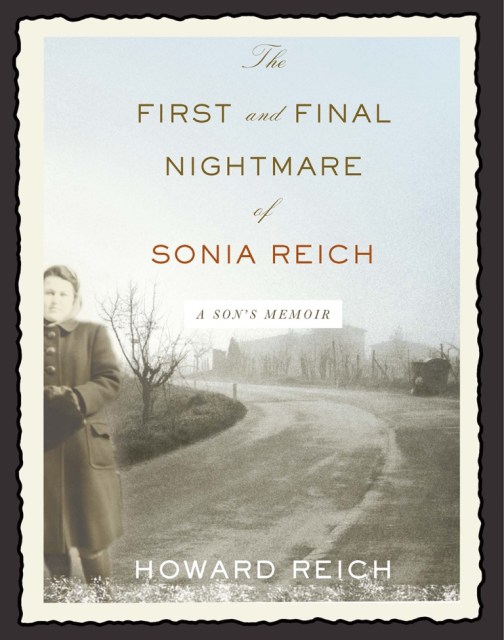

The First and Final Nightmare of Sonia Reich

A Son's Memoir

Contributors

By Howard Reich

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 20, 2009

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786736140

Price

$15.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $15.99 $19.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 20, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

On the evening of February 15, 2001, Sonia Reich, Howard Reich’s mother, packed some clothes into two brown shopping bags, put on her gray winter coat, locked the door to her home in Skokie, Illinois and fled. Someone was trying to kill her, “to put a bullet in my head,” Sonia told anyone who would listen. Polish and Jewish, Sonia Reich had survived the Holocaust by staying always on the run. She and Howard’s father, Robert, also a Holocaust survivor, had fled to America, moved to Chicago, and raised their young son to tell no one that they were Jewish. It was only after moving to Skokie, a town filled with Holocaust survivors, that his family would live as Jews. Still, his parents told Howard almost nothing about their past. The First and Final Nightmare is Reich’s moving and bittersweet memoir of growing up in Skokie, discovering an odd and personal American freedom in jazz, and his riveting, revealing investigation into his family’s past and the nature of his mother’s illness, called late-onset Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. This is a poignant story of a mother and a son, a haunted past, and the irony of what may happen when that often repeated admonition to “never forget” becomes a curse.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use