Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

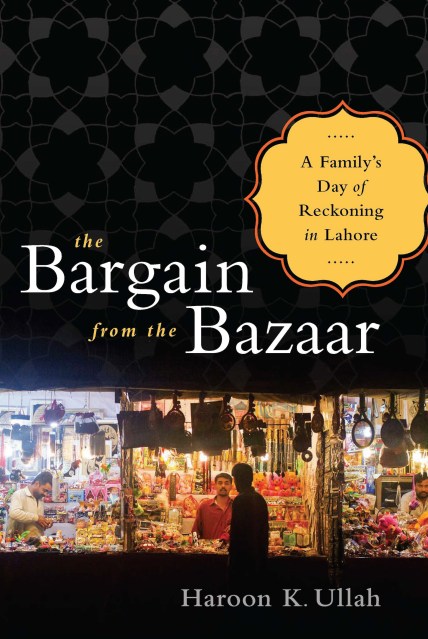

The Bargain from the Bazaar

A Family's Day of Reckoning in Lahore

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 11, 2014

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391672

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 11, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

But Anarkali’s exuberant hubbub cannot conceal the fact that Pakistan is a country at the edge of a precipice. In recent years, the easy sociability that had once made up this vibrant community has been replaced with doubt and fear. Old-timers like Awais, who inherited his shop from his father and hopes one day to pass it on to his son, are being shouldered aside by easy money, discount stores, heroin peddlers, and the tyranny of fundamentalists.

Every night before Awais goes to bed, he plugs in his cell phone and hopes. He hopes that the city will not be plunged into a blackout, that the night will remain calm, that the following morning will bring affluent and happy customers to his shop and, most of all, that his three sons will safely return home. Each of the boys, though, has a very different vision of their, and Pakistan’s, future.

The Bargain from the Bazaar — the product of eight years of field research — is an intimate window onto ordinary middle-class lives caught in the maelstrom of a nation falling to pieces. It’s an absolutely compelling portrait of a family at risk — from a violently changing world on the outside and a growing terror from within.