Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

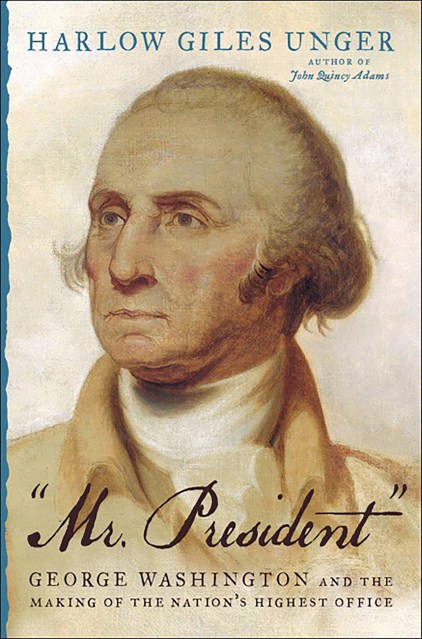

"MR. PRESIDENT"

George Washington and the Making of the Nation's Highest Office

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 29, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Although the framers gave the president little authority, George Washington knew whatever he did would set precedents for generations of future leaders. To ensure their ability to defend the nation, he simply ignored the Constitution when he thought it necessary.

In a revealing new look at the birth of American government, “Mr. President” describes Washington's presidency in a time of continual crisis, as rebellion and attacks by foreign enemies threatened to destroy this new nation. Constantly weighing preservation of the Union against preservation of individual liberties and states' rights, Washington assumed more power with each crisis. In a series of brilliant but unconstitutional maneuvers he forced Congress to cede control of the four pillars of executive power: war, finance, foreign affairs, and law enforcement.

Drawing on rare documents and letters, Unger shows how Washington combined political cunning and sheer genius to seize ever-widening powers, impose law and order while ensuring individual freedom, and shape the office of President of the United States.

Genre:

-

“Mr. President explores both the birth of our nation's government and Washington's continual influence over the role of the president in domestic and foreign affairs, offering some truly enlightening insight into the earliest days of the U.S. government…Washington's political savvy and foresight have never seemed more impressive than they do in Unger's hands…As eye-opening as it is fascinating.”

InfoDad.com, 11/14/13

“Unger's book is essentially a tracing of the roots of what we now call the ‘imperial presidency,' which most people believe to be a purely modern phenomenon—attributed by many to Franklin D. Roosevelt, for example. But Unger convincingly argues that this is not so: the seizing and exercise of powers not given to the president by the Constitution dates back all the way to the nation's first chief executive… It is genuinely fascinating to follow Unger's tracing of so many supposedly modern ‘presidential excesses' to the nation's first president: this book really does shine a new light on social and political conflicts that continue to this day.”

The Heartland Institute (Somewhat Reasonable blog), 11/2/13

“[An] excellent book.”

Roanoke Times, 12/1/13 -

Publishers Weekly, 9/16/13

“[A] fast-paced chronicle of Washington's presidency.”

Washington Times, 11/13/13

“[A] thoroughly researched and delightfully written book…Adds a much-needed new dimension to the Washington portrait…A real thriller of a tale that Mr. Unger has told with skill and authority.”

New York Journal of Books, 10/29/13

“With ‘Mr. President' Harlow Giles Unger gives our precious American history the backbone it deserves and reveals more of Washington the man than Washington the demigod…Mr. Unger has the ability to not let his scholarship weigh down his story. History can be yawn inducing, but Mr. Unger puts his arm around us as if he is a travel companion telling a story—our story—with the pacing of a solid novel…Mr. Unger has objectively stripped away the mythological haze surrounding one of our most important founding fathers.”

San Francisco Book Review/Sacramento Book Review, 11/11/13

- On Sale

- Oct 29, 2013

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306822414

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use